Environment

Environment

Aerogel, an ultralight and versatile material, made for the first time from discarded plastic bottles, might contribute to tackling the global plastic scourge.

|

| A woman walks on trash-covered Hải Bình Beach in the central province of Thanh Hoá. — VNS Photo Việt Thanh |

Trọng Kiên

HÀ NỘI — Despite being a fairly new material with a little over 100 years of history, plastic has permeated every part of modern life.

But plastic’s very strengths – convenience, cost and durability – have proved a double-edged sword and turned it into an increasingly menacing, ubiquitous and resilient threat to the environment once the one million bottles produced a day have outlived their original purpose.

A team led by two Vietnamese researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Assoc. Prof Dương Minh Hải and Prof Phan Thiện Nhân, have found a way to breathe new life into discarded plastic bottles – turning them into one of the world’s lightest material called ‘aerogel’ that has a wide range of applications, including heat insulation, sound insulation, and absorption of oil and other pollutants.

“I wanted to come up with a real product for everyone, after a lifetime of producing theories,” Hải said.

They wanted to show that engineering and technology could help reduce the amount of plastic waste which would otherwise clog up landfills or end up in the ocean for hundreds of years, and buy us more time to find the ultimate answer to the scourge of plastic as no viable alternatives have cropped up.

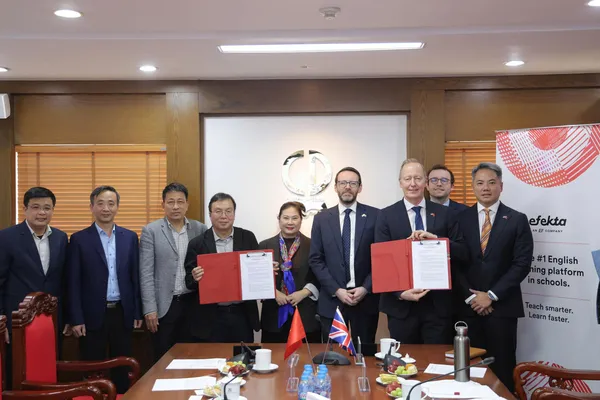

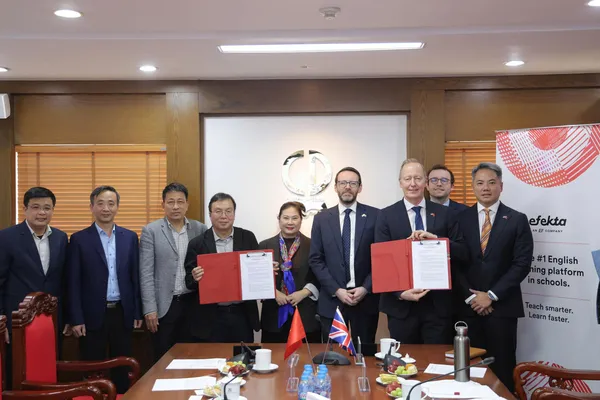

|

| Assoc Prof Dương Minh Hải (left), Nguyễn Võ Tuấn Huy (right) and Prof Phan Thiện Nhân sign intellectual property rights to license aerogel technologies to the Việt Nam-based DPN Aerogel JSC from the National University of Singapore. — Photo courtesy of Dương Minh Hải |

Green recycling

The abundant plastic bottles, primarily made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET), would be shredded into tiny fibres, placed onto a tray and mixed up with a combination of water and a little chemical in a sonar machine.

The homogenous substance would then be frozen in a freeze-dryer for about eight hours and the liquids removed through sublimation.

The entire process, which lasts for about 10 hours, compared to nearly a week it took to produce pure silica aerogel, would turn a plastic bottle into a sheet of ultralight and porous aerogel having the size of A4 paper.

Aside from the shorter fabrication time and use of less expensive equipment, the PET aerogel also claims superiority over its predecessors because it doesn’t involve toxic solvents that could irritate the skin or eyes, Professor Nhân said.

“When I came to Singapore, when I was attempting to dispose of some scraps but couldn’t find a recycle bin so the cleaners asked me why I didn’t just find another use for them instead of throwing them away, so I took that as a challenge,” Hải told Việt Nam News about the origin of his endeavours that spawned the trilogy of “eco-aerogel” from fabric, rubber, and the latest ’waste’, PET plastic.

However, Hải observed that the recycling process only produces low-value products so people are not really interested in collecting or recycling them in the first place.

“So I wanted to create something valuable from the waste. For example, if people know that a plastic bottle could be used to make a material that could sell for $20 then they would want to keep them for recycling instead of discarding them as litter.”

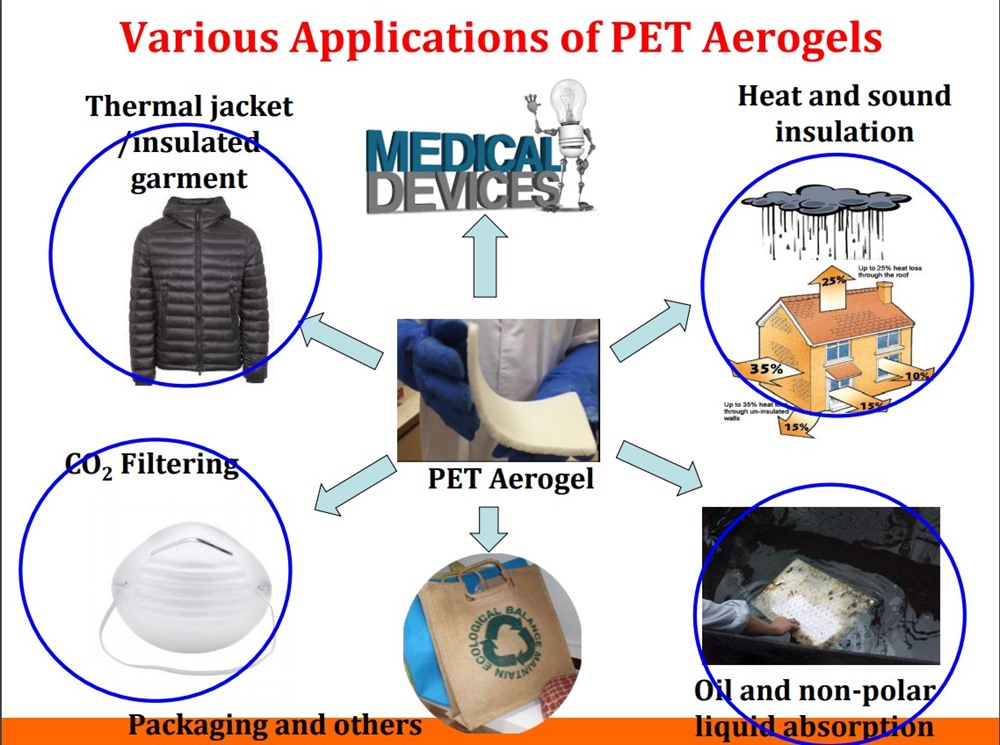

The aerogel also supposedly boasts superior effectiveness in various applications compared to existing commercial products on the market.

“Based on our experiments, regarding heat insulation, PET aerogel is seven times better. Its soundproofing capacity is 30 per cent higher than the most used material called Basmel,” Nhân said.

The material could endure heat of 620 degrees Celsius – seven times higher than conventional thermal lining materials but ten times lighter, making it extremely useful in case of fires at high-rise buildings, Nhân said, giving people a longer window to escape with less burn injuries and lower risks of smoke inhalation.

Hải and Nhân also suggested that the aerogel could potentially be used to line the walls of Việt Nam’s cars, future North-South expressway trains, urban metro and future bullet trains as its ability to absorb heat and sounds could reduce the power demands for cooling and cut back on noise reaching passengers.

The aerogel also proves to be highly capable in absorbing more tangible materials as well, being able to soak up as much as seven times the amount of oil taken up by using polypropylene, the plastic most widely used as absorbent.

“One gram of solid PET aerogel could absorb up to 100g of oil, or 90-100 times their weight. PET aerogel reaches its maximum capacity in under one minute while the polypropylene products take up to five minutes,” Hải said.

|

| Proposed applications of PET aerogels. — Illustration courtesy of the research team |

All-round solution

Ideally, PET aerogel would be collected and PET fibres made into another batches of aerogel, but even if left untreated in nature, PET aerogel would decay completely within 20-50 years, vastly quicker than the 450-year duration of the original PET from which it derived.

“We aim for the long-life and high value engineering applications, not for the single use and low-value applications like plastic straws. For some applications such as heat and sound insulation in buildings, aerogels can last more than 20 years without breaking their structures and releasing dust particles into the buildings,” Hải said.

Prof Nhân stressed that the recycling method matters and the team is mindful of the need to not cause more burden on the environment and strive for a green fabrication method that involves mostly water, and very little at that – 1cu.m. of water for 100sq.m of aerogel.

“The total cost for recycling plastics, which needs energy and a lot of chemical substances, might be even larger than the ‘costs’ incurred by simply leaving the plastic waste decomposing in nature,” he said.

|

| Assoc Prof Dương Minh Hải and Prof Phan Thiện Nhân hold up a sheet of aerogel made from PET plastic bottles and a fire-retardant coat with an aerogel lining. — Photo courtesy of Dương Minh Hải |

Well-received technology

PET aerogel is one of the more successful inventions that makes its way from the lab to the market, as its usefulness comes with a production process that is “easily scalable for mass production.”

So far, the technology has attracted 25 inquiries from companies from the US, Australia, UAE, Switzerland and a number of Asian countries including China, who seek to obtain sub-licences of intellectual property rights.

Major players in the beverage industry and aviation have also expressed interest, the research team said, likely based on their heavy use of plastics in their packaging and services, i.e. bottles, food and drink trays or other components on airplanes.

“Singapore’s National Environment Agency under the Ministry of Environment and Water Resources has facilitated the meetings between us and local companies,” Hải said, adding that Indonesian companies have also proferred to set up joint ventures.

In the case of Việt Nam, the HCM City-based DPN Aerogel JSC last week received exclusive IP rights from NUS to produce eco-aerogels from fabric waste, rubber and plastic.

DPN expects to produce 100,000sq.m of aerogel per year for the first production phase and launch its commercial products in 2020, with Hải and Nhân serving as the company’s technology consultants.

DPN Aerogels JSC aims to have the “100 per cent made-in-Việt Nam high technologies” and can “re-sell” their aerogel technologies to foreign companies.

Nguyễn Võ Tuấn Huy, CEO of DPN Aerogel, said that Nhân and Hải care deeply about the development of Việt Nam and hope that Việt Nam is one of the first places to deploy their technologies, to help address the pressing environmental concerns arising during the country’s fast growth and enhance daily life quality of Vietnamese people.

He referred to Việt Nam’s position as one of the top offenders in discharging plastic into the ocean and wished that the aerogel products could help alleviate the situation and furthermore, engender a new awareness among the public regarding recycling and the use of plastic as a whole.

The trio’s next target would be making aerogel from the growing heaps of ash and slag, the main waste of coal-fired thermal power production that demand enormous landfills to store while the recycling rate – mainly to produce non-fired construction materials – has been lacklustre.

As the Government deems it necessary to expand this type of fossil-based electricity to feed the increasing power demands of the economy, a move widely condemned by environmentalists and the public, Huy said their aerogel solution would use this very source of pollutants to fight off pollution, via a range of eco-friendly, high-value carbon-based products to filtre water and air. — VNS