Society

Society

|

| Associate Professor Trần Thị Định mentions the three pillars of risk analysis: risk management, risk assessment, and risk communication. |

Phương Dung

In mid-October, Vietnamese and Canadian food safety officials gathered in Đà Nẵng to discuss something that rarely makes headlines but shapes how nations protect their citizens: Food Safety RISK. They were not debating scandals or announcing new regulations. Instead, they examined how science, management, and communication can work together to prevent food safety crises before they happen.

From crisis response to risk prevention

Unsafe food causes around 600 million illnesses and more than 400,000 deaths each year worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. Children under five account for almost a third of those deaths. These numbers highlight a shared global challenge: how to move from responding to outbreaks toward systematically preventing risks.

“Zero risk does not exist,” said Associate Professor Trần Thị Định, the National Food Safety specialist of the SAFEGRO project “However, we can make better decisions when they are based on scientific evidence.”

She mentioned the three pillars of risk analysis: risk management, risk assessment, and risk communication. Together, they provide a scientific, policy, and social framework for ensuring food safety. She compared a national food safety system to a house. Its foundation is strong regulation, its pillars are these three disciplines, and its roof is institutional coordination. When these components work together, they not only protect public health but also promote fair trade practices and build trust.

Lessons from Canada’s risk-informed system

Canada’s experience offered a practical example of how a risk-informed system operates. Rowena Linehan, National Food Safety Risk Manager at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), described how the Safe Food for Canadian Regulations, issued in 2019, consolidated fourteen separate laws into one risk-based framework.

Its key reforms, including licensing, preventive controls, and traceability, shifted the responsibility for food safety toward producers, processors, and importers, allowing CFIA to focus on oversight and prevention.

“The key is not to control everything,” Linehan explained. “It is to focus where it matters most.”

This shift reflects CFIA’s philosophy of integrated risk management, which recognises that food, animal, and plant health systems are interconnected and that data driven prioritisation is more effective than blanket inspection programmes or end-product testing currently used in Việt Nam.

Science at work: Modeling risk to save lives

CFIA’s Food Import Risk Explorer (FIRE) model is one example of a decision-making tool that quantifies the public health burden of different food and hazard combinations using Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) as the outcome indicator.

Dr. Ashwani Tiwari, one of CFIAs’ leading food safety risk assessment managers, explained that the model helps Canada focus on the products and sources posing the highest risks and to measure how new policies reduce illnesses caused by pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter.

Such quantitative approaches, he noted, allow CFIA to allocate resources where they can save the most healthy years of life per dollar spent for domestically produced food and imports. This idea resonated with Vietnamese participants, who face similar constraints with limited inspection capacity or budgets and vast numbers of small producers.

|

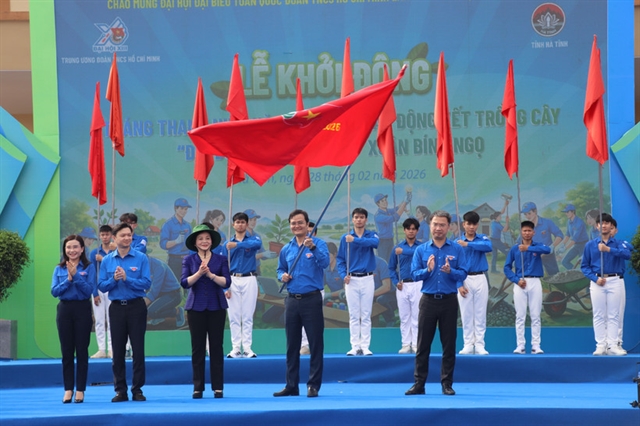

| Vietnamese and Canadian food safety officials gather in Đà Nẵng in mid-October to discuss Food Safety RISK. Photos courtesy of SAFEGRO |

Việt Nam’s emerging risk infrastructure

Việt Nam’s Food Safety Law of 2010 already defines risk analysis, but implementation has been inconsistent. The creation of the Vietnam Food Safety Risk Assessment Center, VFSA, in 2024, under the National Institute for Food Control, NIFC, marks a turning point.

According to its director, Associate Professor Trần Cao Sơn, the center’s goal is to build data systems and analytical capacity to guide evidence-based decision making. VFSA is now conducting quantitative risk assessments on Salmonella in chicken, histamine in fish, and chemical contaminants in infant formula, with support from the SAFEGRO project and CFIA.

“We are learning to turn data into action,” Sơn said during discussions. “From assessing and managing risks to communicating them clearly, it is all part of building a culture where food safety becomes a habit, not just a regulation.”

Decision making and the human element

If the elite team of risk assessors provide the scientific evidence, risk managers translate it into policy and action. As Greg Paoli, CEO of Risk Sciences International, emphasised, risk management is not a formula but a mindset.

He urged that decisions must be risk-informed, guided by scientific evidence yet sensitive to social and economic realities. He also highlighted the principle of proportionality. With finite resources, regulators must focus on interventions that yield the greatest risk reduction per dollar.

But science alone is not enough. How people perceive risk and how institutions communicate it can determine whether a policy succeeds.

Laura Hepditch from CFIA presented Canada’s experience in risk communication, stressing that transparency builds trust even when information is incomplete. She described how CFIA addresses misinformation by communicating early, correcting errors publicly, and ensuring that official websites provide reliable, updated information.

Paoli expanded on this by explaining that perception often depends on trust and values. People fear involuntary or unfamiliar risks more than those they choose. Therefore, effective communication requires empathy, clarity, and credibility, not just technical accuracy.

SAFEGRO: Building bridges for a food safety culture

Funded by the Government of Canada, the SAFEGRO project connects international expertise with Việt Nam’s ongoing effort to modernise its food safety system. Its goal is not only to strengthen institutions but also to help farmers, vendors, and consumers understand and manage food safety risks in everyday practice.

Through its partnership with CFIA, SAFEGRO has supported Việt Nam’s ministries of Health, Agriculture and Environment, and Industry and Trade in adopting risk-based approaches. The project has helped review and update food safety regulations, develop laboratory information management systems, train food safety managers, and conduct studies on key products such as pork, vegetables, and fisheries.

Its impact is most visible in risk communication. At the Mía market in Đường Lâm, SAFEGRO worked with vendors to improve hygiene through open dialogue, storytelling, and visual tools rather than inspection or enforcement. By linking food safety to pride, livelihood, and personal responsibility vendors began changing to safer daily behaviours.

At the workshop’s closing session, Brian Bedard, the SAFEGRO’s International Food Safety Specialist, summed up the project’s philosophy: ensuring food safety is not about catching unsafe food, but about preventing risks before they occur. True food safety, he said, depends on understanding, cooperation, and shared responsibility among government, businesses, and citizens.

Toward a culture of shared responsibility

The transformation Việt Nam is pursuing is not simply regulatory; it is cultural. It requires scientists who communicate clearly, regulators who act transparently, and citizens who understand that safety is everyone’s concern.

As Paoli reminded participants, risk never disappears, but by understanding it, societies can live more safely. The Đà Nẵng workshop did not issue new decrees, yet it marked a deeper shift, a move from control to collaboration, from reaction to prevention, from isolated enforcement to a culture of shared accountability and responsibility.

If that mindset takes root, Việt Nam’s food safety system will detect problems before they occur and prevent them. And that quiet, deliberate progress toward food safety culture may be the most meaningful change of all. VNS

.jpg)