Features

Features

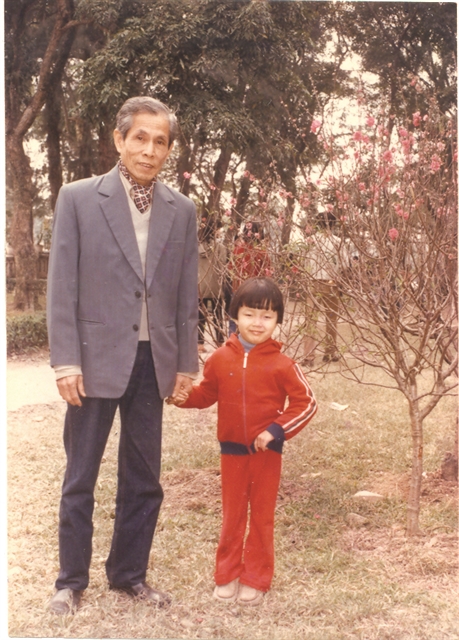

|

| Nguyễn Văn Mỹ (middle), with his daughter and grandson, revisits memories from his youth through a family photo album. — VNS Photo Đoàn Tùng |

Lê Việt Dũng

Tens of thousands gathered at Ba Đình Square in Hà Nội to witness a defining moment in Việt Nam’s history on September 2, 1945. Among them was 20-year-old Nguyễn Văn Mỹ, who stood in the front row as President Hồ Chí Minh read aloud the Declaration of Independence, giving birth to the Democratic Republic of Việt Nam.

“From afar, I saw President Hồ on the stage,” Mỹ recalled, his eyes still shining with the clarity of that memory nearly eight decades later.

“President Hồ asked, ‘Compatriots, can you hear me clearly?’ and the whole square answered in one voice, ‘Yes!’ It was like thunder rolling through the air. That was the very day we knew we had become free citizens of an independent Việt Nam. The happiness was overwhelming. We were ready to sacrifice everything to defend that freedom.”

Born on April 30, 1925, in Hà Nội’s Old Quarter, Mỹ grew up in a family of merchants on Hàng Đồng Street. From a young age, he witnessed the stark inequality and humiliation of colonial rule.

Ordinary Vietnamese lived in grinding poverty, burdened by heavy taxes and relentless levies imposed by the colonial and feudal regime, while being forbidden from entering French-only parks, restaurants and theatres.

“I witnessed the contrast every day,” he said. “Buffalo carts and crowded trains full of poor Vietnamese peasants on one side, while the French officials rode by in their shiny cars on the other. The injustice sank into me and I carried a silent anger inside.”

That anger slowly crystallised into a longing for independence.

“I didn’t know how independence could be achieved then,” he admitted. “But I was sure of one thing: if it ever came, it would come only after a great struggle against the French.”

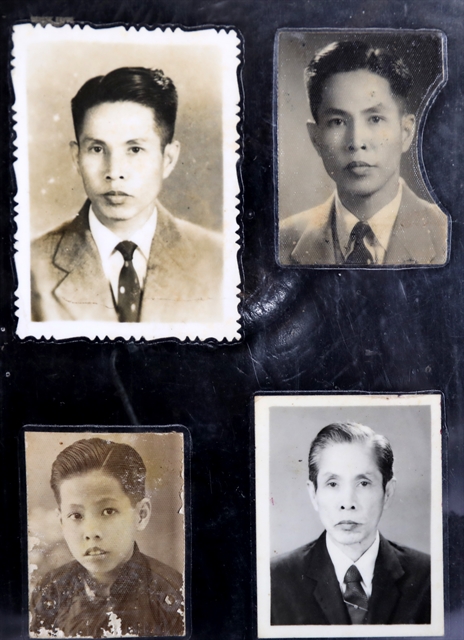

|

| A series of portraits of Nguyễn Văn Mỹ, from his teenage years to youth, middle age and later life. |

As a teenager, Mỹ studied at Thăng Long High School, founded in 1928 by educator Hoàng Minh Giám. The school soon became a hub of nationalist fervour, where many teachers would later play leading roles in the anti-French war.

Đặng Thai Mai, who later became Minister of Education, and Phan Anh, later Minister of Defence, both taught there. Surrounded by their example, Mỹ quickly absorbed the atmosphere of resistance.

By the early 1940s, student protests and strikes were spreading across Hà Nội, and the French authorities cracked down hard. Many students, including Mỹ, decided to drop out of their studies and throw themselves into the revolutionary cause.

Soon, he was recruited by the Việt Minh – short for the League for Independence of Vietnam, a revolutionary movement led by Hồ Chí Minh, who asked Mỹ to serve secretly as a commune chief in Yên Xá, a rural area on the outskirts of Hà Nội.

The assignment was dangerous. Việt Nam was under what many described as a 'double yoke' – French colonialists still wielded power, yet by 1940 the Japanese had forced France to surrender its military control of Indochina.

In March 1945, the Japanese staged a coup, turning the colony into a Japanese stronghold. For young revolutionaries like Mỹ, the situation was tense but also full of possibilities.

When news arrived in mid-August 1945 that Japan had surrendered, the Việt Minh wasted no time. On August 13, they issued a nationwide call for uprising.

On August 19, Mỹ joined the surging crowds that seized power in Hà Nội and two weeks later, he stood in Ba Đình Square for the Declaration of Independence event.

"That day was pure joy," he said. "It felt like the iron chains of a century had finally fallen away."

The euphoria, however, proved short-lived. By late 1946, French forces had returned, intent on reclaiming Indochina. On December 19, 1946, President Hồ Chí Minh issued the Call for National Resistance.

For more than 60 days, the people of Hà Nội built barricades, fought street by street and held off French attacks to buy time for the resistance government to evacuate safely to northern mountainous provinces. Mỹ was among them.

"We fought with whatever we had," he said. "When the order came to withdraw, we left secretly along the Red River. I carried a sword, a lightweight aluminium bicycle and one belief carved deep inside me: that we would return victorious."

That belief sustained him through nine long years of resistance. The hardship was immense, but hope never wavered. In May 1954, the victory at Điện Biên Phủ finally forced France to sign the Geneva Agreement, restoring peace in Indochina.

"On September 2, 1954, though I was still in the Resistance Zone, my heart was at Ba Đình," Mỹ said. "I felt as if I were standing there again, this time hearing the cheers of triumph."

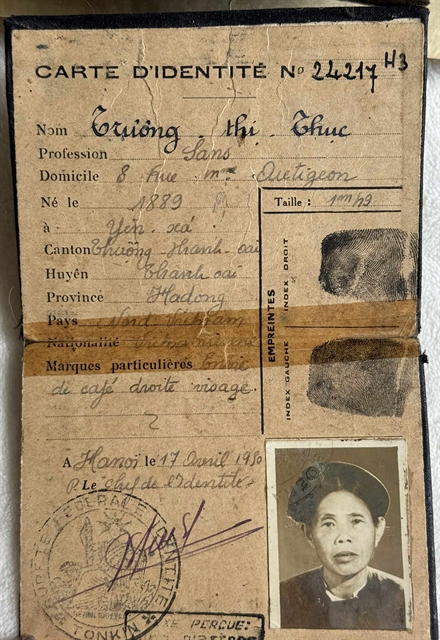

When he returned with his department to Hà Nội later that month to prepare for the official handover of the capital, he carried both joy and sorrow: news reached him that his mother had passed away while he was still in the Resistance Zone.

The only keepsakes were her identity card and his father’s glasses, which he has carefully kept all his life.

|

| The identity card of Nguyễn Văn Mỹ’s mother, issued under the French colonial administration in 1930. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

Mỹ resumed life in Hà Nội, beginning the long work of rebuilding a country still divided. Material life was modest, but his faith in eventual reunification never wavered.

He joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1954 and, eleven years later, became part of the inaugural class of the newly established Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. It marked the beginning of a three-decade journey in diplomacy that would take him across the world.

In 1971, he married, but the demands of service soon carried him to postings in France, Switzerland, India, China and the Soviet Union, keeping him far from home.

|

| Nguyễn Văn Mỹ during his service overseas. |

When the US escalated its bombing campaign in the North, Hà Nội was plunged into a rhythm of sirens and hurried descents into air-raid shelters. Families carried on with remarkable resilience, sharing the same spirit of sacrifice that united the nation.

Then came April 30, 1975. While on duty at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mỹ received the news that Sài Gòn – the capital city of the US-backed regime – had fallen. It was his 50th birthday.

"It was the greatest birthday gift of my life," he said.

On September 2 that year, he once again stood in Ba Đình Square, this time to celebrate the first National Day of a unified Việt Nam.

"If 1945 was the day I became a citizen of an independent country, then 1975 was the day I truly lived in a unified Việt Nam."

Yet even after reunification, life remained difficult as the US embargo cast a long shadow and daily life was bound by ration cards and coupons. Families queued for rice and pork; goods were scarce.

Mỹ retired in 1985, and in that same year, he took his wife and four-year-old daughter to HCM City for the first time since reunification, determined to show her the wholeness of the nation.

|

| A family photo of Mỹ’s wife and daughter when she was a child. |

On September 2, 1985, the family watched the 40th anniversary parade from the balcony of their apartment on Nam Bộ Street (now Lê Duẩn Street).

"It was immense pride," he said, "but I also felt a heavy heart, seeing how hard life still was. That parade reminded us of our heroic past, but also lit a spark of hope for the future."

That spark took shape the following year with the launch of the Đổi Mới (Renewal) reforms.

"I witnessed Việt Nam shedding its old skin," Mỹ said. "From rationing to open markets, from isolation to integration. It was a transformation beyond anything we could have imagined during the difficult years of the embargo."

In 1995, when Việt Nam celebrated 50 years of independence and normalised relations with the US, Mỹ stood watching the parade beside his 14-year-old daughter.

"I looked at her, a child born in peace, growing up as the country opened to the world, and I felt great hope. Our generation fought for independence, but hers would build a strong and prosperous nation," he said.

Even after a stroke in 2008, he never missed a National Day. On September 2, 2015, he sat before his television, watching the army march proudly through Ba Đình once again.

"I remembered 1945, when we had only rifles and spears," he said. "Seventy years later, I saw a modern army and a nation with a growing position on the international stage. From a poor colony, we had come so far. I was deeply moved."

Now, as Việt Nam prepares to celebrate the 80th anniversary of its independence on September 2, 2025, Nguyễn Văn Mỹ has reached the age of 100. Frail but lucid, his gaze is still fixed on the future.

"Never forget the value of peace and independence," he urged younger generations. "They were bought with the blood of countless compatriots. And always stay united. Learn, reach out to the world, but never forget your roots."

Looking back over a century, he said his greatest pride is the resilience of the Vietnamese people.

"We rose from the ashes of war, from hunger and rationing, to reach today. That is a miracle," he said.

|

| Mỹ and the radio he used to hear the historic news of Sài Gòn's liberation on April 30, 1975. VNS Photo Đoàn Tùng |

For Mỹ, September 2 is not just a date on the calendar. It is the living heartbeat of a nation – a reminder of sacrifice, struggle and renewal.

From a young man in the front row at Ba Đình in 1945 to a centenarian today, his eyes still shine with the same unwavering faith: faith in Việt Nam’s independence, and in its "new era of nation’s rise." — VNS