Features

Features

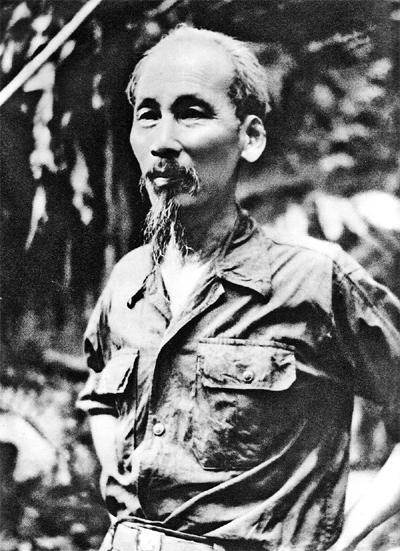

Vietnamese friends who could remember the end of World War II have all said that Việt Nam's August Revolution in 1945 and re-unification in April 1975 could never have succeeded without Hồ Chí Minh. Details they shared lead me to thoughts about President Hồ as a military strategist.

|

| President Hồ Chí Minh, founder of the Việt Nam Liberation Army Team, the predecessor of the Việt Nam People’s Army. VNA/VNS File Photo |

by Lady Borton

They all said it, sometimes even quoting poetry.

Vietnamese friends who could remember the end of World War II have all said that Việt Nam's August Revolution in 1945 and re-unification in April 1975 could never have succeeded without Hồ Chí Minh. Details they shared lead me to thoughts about President Hồ as a military strategist.

In 1913, early in his thirty years overseas (1911‒1941), Hồ Chí Minh worked as a pastry sous chef at Boston's most prestigious hotel. He wrote English words on his forearms to study vocabulary while kneading dough for Parker House rolls. While abroad, Hồ Chí Minh learned ten foreign words a day, gaining fluency in Cantonese, English, French, Mandarin, Russian, and Thai. He wrote his most famous poems in Chinese ideographs.

Hồ Chí Minh was a lifelong learner. During those thirty years, he earned the equivalent of seven academic degrees—an MA in American Studies (Boston, 1913), a PhD in British Colonialism (London, 1913‒1917; Hong Kong, 1930‒1934), a PhD in French Colonialism (Paris, 1917‒1923), an MA in Leninism while interpreting for the twenty-member Comintern (Communist International) Executive Committee (Moscow, 1923‒1924), a PhD in Stalinism (1927, 1934‒1938), a PhD in Guomindang Revolutionary Studies (Canton now Guangzhou, 1924‒1927), and a PhD in Communist Chinese Revolutionary Studies (Yan'an, 1938‒1941).

Those years gave President Hồ skills as a savvy diplomat. Seldom noticed are his three years (1924‒1927) interpreting for Mikhail Borodin, the Comintern military advisor whom [Soviet leader Vladimir Ilyich] Lenin had sent to Canton (now Guangzhou) to train the Guomindang. Hồ Chí Minh was officially a Chinese staff member using the alias Lý Thụy at RÔXTA, a Soviet firm. He interpreted in Russian, Chinese, and in Vietnamese for his own revolutionary recruits. Interpreters must master instructors' material and present it precisely. Hồ Chí Minh's additional challenge was to provide the three-sided, martial-history context necessary to make Borodin's content understandable. This equivalent PhD in Military Science gave President Hồ skills as a shrewd military strategist.

***

|

| President Hồ Chí Minh talks with high-ranking officers and men of the Việt Nam People’s Army in the 1950 Border Campaign. VNA/VNS File Photo |

In the United States, academics holding multiple PhD's are famous for destructive competition, but Hồ Chí Minh masked his sophistication. In early 1941, he wore the indigo-dyed clothes of Tày and Nùng ethnic minorities and learned their languages while hiking back to Việt Nam from China. Local people in Cao Bằng called him Già Thu (Elder Thu) or Cúng Sáu San (The Elder in the Jungle). Unlike academics threatened by others' brilliance, Hồ Chí Minh attracted talented, skilled people. He made careful staff choices and gave his appointees crystalised guidance.

Võ Nguyên Giáp and Phùng Thế Tài are good examples.

Võ Nguyên Gíap (1911‒2013) until 1944 had no military training. Yet in December of that year, Hồ Chí Minh chose him to lead the first unit of the armed forces over other possible candidates, who had studied military science in China. He knew Giáp had researched weapons in the National Library and knew Giáp had been a history teacher. During French colonialism, "history" meant French history, specifically French wars. To prepare his class lectures, Giáp scrutinized writings by French generals. He diagramed their battles. He understood better than his fellow revolutionaries trained in China how Việt Nam's French enemy thought and fought. Giáp's round face and small stature belied his skills. The French underestimated Giáp, calling him "le petit professeur" (the little teacher).

Hồ Chí Minh needed an army leader with organizational skills, and he needed Giáp's personal magnetism. Giáp had learned Tày and Nùng languages. He lived easily with local people, entrancing them with his early-morning martial arts and amusing them but earning their sympathy with his toxicity to liquor. He had learned from Hồ Chí Minh how to talk simply about world events and the French enemy. He emphasised secrecy. In village after village, Giáp organized five secret Việt Minh Associations for National Salvation—farmers, women, youths, elders, and children.

Hồ Chí Minh tucked into a cigarette pack his directive for forming the army: "1. Name: Đội Việt Nam Tuyên truyền Giải phóng quân. This means that the political is more important than the military: This is a publicity unit. …[C]hoose from the ranks of the Cao Bằng – Bắc Cạn – Lạng Sơn guerrilla units the officers and troops who are most ardent and resolute." Giáp knew the best men to recruit. Only four of his first thirty-four troops were from the Kinh ethnic minority. Twenty-eight were Tày or Nùng ethnics.

Hồ Chí Minh directed Giáp: "Within one month, you must stage an action to establish confidence for the warriors and a tradition for our soldiers of speedy, zealous action." Two days after the unit formed, Giáp organised a complex surprise attack against the French base in Phai Khắt, a Tày village. The secret village Việt Minh Associations built over years provided support, including intelligence, ensuring success. Beginning with Phai Khắt, Võ Nguyên Giáp built the army as Hồ Chí Minh had written in his directive's conclusion: "At the beginning your size is small, but your future is bright. You are the genesis of the Liberation Army, which will march from South to North, across our entire Việt Nam."

|

| President Hồ Chí Minh visits an army unit participating in the Border Campaign in Cao Bằng Province, in March 1951. File Photo |

In 1951, when a senior military intelligence officer tempered his intelligence report to Hồ Chí Minh for a delicate reason, President Hồ's response was unequivocable: Under no circumstances should an intelligence officer temper his information to fit what his superior wanted. Never. An intelligence officer must always tell the truth as he saw it, as he knew it. Otherwise, President Hồ reasoned, how could a superior officer make an incisive decision?

Later, President Hồ's guidance to the intelligence officer helped save the PAVN from disaster.

In January 1954, General Giáp arrived at the Việt Nam People’s Army's outpost in the mountains surrounding the French camp in Điện Biên Phủ Valley. His units were excited about a recently revised strategy, "Fast Strike. Fast Victory", to capture the French base in three days and nights. General Giáp was apprehensive. His troops would be fighting in an open plain with no cover, but their expertise was fighting and hiding in the mountains. His army would be slaughtered. But morale for a Fast Strike was high. For ten days the likelihood of disaster haunted Giáp.

Then he received "unpopular" intelligence.

The French had captured a VNPA soldier and learned details of the planned opening assault by the VNPA's 308th ("Steel") Division. Further, they had decoded Vietnamese supply messages and knew the VNPA lacked rice for sustained combat. They planned to crush the 308th Division with a surprise pincer attack. Faced with this news, General Giáp checked each source of information the army intelligence unit presented. The "unpopular" intelligence was a deciding factor in Võ Nguyên Giáp's "hardest decision as a military commander." General Giáp ordered the VNPA to withdraw from Điện Biên Phủ for sustained re-training to prepare for a revised strategy, "Steady Attack. Steady Advance", in the spirit of the instruction he received earlier from Hồ Chí Minh when he was entrusted with total decision making power, and the assault that began on March 13 achieved victory on May 7, 1954.

***

Another example of President Hồ's strategic guidance for an appointee was in 1962. General Phùng Thế Tài (1920‒2014), recently chosen as Air Defence commander, had a congratulatory meeting with the president. In 1944, young Phùng Thế Tài had been Hồ Chí Minh's first bodyguard. After congratulating General Tài on his appointment, President Hồ said, "Tài, have you heard of B-52s? Our current anti-aircraft can't touch B-52s. They fly too high. Starting now, as Air Defence commander, you must concentrate on B-52s."

"I was stupefied," General Tài said. "B-52s! I didn't know what Uncle was talking about."

With President Hồ's foresight, in 1964 children and non-essential workers were evacuated from Hà Nội and other cities. In July 1966, President Hồ predicted the USA would send B-52s to bomb Hà Nội and Hải Phòng. American bombing of Hà Nội (but not yet with B-52s) began a few months later, in December 1966. In early 1968, shortly after the Tết Offensive, President Hồ warned General Phùng Thế Tài, "Sooner or later, the American imperialists will send their B-52s to strike Hà Nội. Only when we have defeated the Americans in that battle will the USA accept defeat."

With Hồ Chí Minh's early warnings, Việt Nam's Air Defence secured the Soviet Union's support to build missile sites with Soviet equipment, but the Soviets provided only a few missiles. The Vietnamese drew on experiences downing B-52s near the DMZ to develop their own Red Handbook, which assured optimal use of their missiles. In December 1972, the Air Defence defended Hà Nội for twelve days and nights during Điện Biên Phủ in the Air.

***

Years earlier, in the early 1940s, Hồ Chí Minh had crystalised his military guidance in Prison Diary, writing in Chinese ideographs the poem many retired generals quote:

Learning to Play Chess

Cramped and miserable, we play chess,

Horses, men circle in perpetual pursuit;

They assault and retreat like lightning,

Nimble feet, keen talent assure victory.

Watch far afield, focus deliberations,

Be steadfast. Never abandon the assault;

One hapless step: Two chariots ravaged.

The right opportunity: A victorious pawn.

The two forces start balanced and equal,

After victory, only one sovereign reigns;

Assault, defend, never relax your guard,

Only a victorious general achieves fame. VNS