Society

Society

|

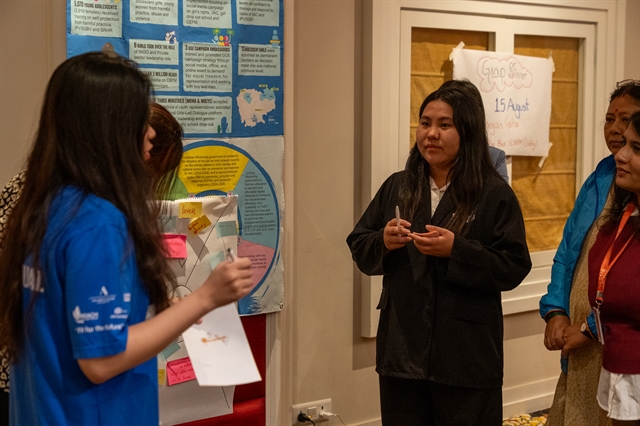

| Sùng Thị Sơ speaks out against forced and early marriage at an Asia-Pacific conference on child marriage in Nepal last year. — Photos courtesy of Sơ |

Khánh Dương

HÀ NỘI — Sùng Thị Sơ, a young Mông ethnic girl from Yên Bái Province, would have given up on her desire to go to college at the age of 18 and instead become a wife and mother if she had not had the courage to fight against a local outdated custom.

Having escaped three times from being kidnapped and forced to get married at an early age, Sơ became the first girl in her village to be admitted to university.

Mông ethnic group in the Việt Nam’s northern mountainous area has a custom known as 'wife stealing', which permits local men to forcefully ask any girl of their choice to become their wives regardless of the girls’ consent.

Sơ was abducted twice, when she was 14 and 16 years old, but was able to flee with the assistance of her father and other relatives.

But the third time was more horrifying.

Four years ago, when she was staying at home alone and studying to prepare for the high school graduation exam, two men broke into her house and pulled her on a motorbike ride, taking her to their place which was 30-40km away.

Sơ said, “I knew one of them as my neighbour's relative, but I do not know his name or how old he was.

"I had a bunch of escape plans like getting off the bike or calling for assistance as we got close to the local police station. But none of those could really happen. My phone was confiscated.

“I had to sleep with the man who wanted to kidnap me. That was a horrifying sleepless night as I resisted the entire night.

“My attempts to escape seemed to be almost hopeless as it is believed that once the kidnapped girl enters the gate of the man’s house, she will become a member of that family and will not be accepted back to her parents’ house. When she dies, her spirit will also belong to that family.

“One night and then two nights I could not do anything to escape. I told the man over and over again” ‘I will not marry you’, ‘I will not marry you’.

“When I eventually got my phone back, I called my father, who told me I could do anything I wanted if I didn't want to get married. My father’s supportive attitude motivated me.

“On the third day, the family eventually decided to let me return home after realising how determined I was, on the condition that they would set up an engagement ceremony.

“Coming back home, my father and I faced pressure from other villagers who tried to persuade us that was a good family. They even gave me and the man three more days to get to know each other and make a decision.

“But I said no to everyone.”

Escaping a forced marriage and aged 18, a few months later Sơ passed the university entrance exam to the Hà Nội Law University and came to the capital city to realise her study dream.

"My desire to flee poverty drove me to escape from the kidnapping,” she told Việt Nam News.

“My family is very poor. Despite the fact that my great-grandparents, my grandparents and my parents worked hard in the fields, we never had enough food. I simply wanted a meal to eat, a coat and a pair of shoes to wear throughout the cold. I never stopped believing that I had to go to college, even when I was being held captive in a forced and early marriage.

“When we have a goal, we are determined to remove any barriers that block our way. I don't want to become a victim of domestic abuse which I witnessed in my own family and in my ethnic group since I was a young child,” she said.

|

| Sùng Thị Sơ is the first girl in her village to be admitted to a university. |

She said ethnic men in her community are automatically given the authority to make decisions on the lives of the women they marry by beating and insulting them, while women have to handle an excessive amount of household chores and suffer greatly from both physical and mental health issues.

"I will undoubtedly never lead such a miserable life,” she said.

From victim to agent of change

Now at the age of 22, Sơ has completed her bachelor studies at the Hà Nội Law University and is offering free legal advice to Mông ethnic people who require support.

"There are numerous instances where a violent woman wishes to file for divorce, but her husband disagrees. They seek out me for legal assistance because they are unable to flee acts of violence," said Sơ.

“In some other certain cases, the woman does not know how to defend her rights in the event of a dispute because the man and woman do not have a marriage registration certificate.

"I want to stand up for women who experience domestic violence. Men have no right to treat women violently, either physically or mentally. I am aware that many women suffer their entire lives because there is no helping hand out there.

“I can become one of the helpers.

“I believe that every individual should be enabled to protect themselves. Many questioned why, at the time of my kidnapping, I did not notify the police. However I could not file a lawsuit against the kidnappers as I did not save any evidence. Having been abducted three times, I believe I should learn more about legal affairs. That’s why I decided to study law.”

There is an additional risk now from the internet which could increase the numbers from ethnic communities forced into early marriage and Sơ recently launched her own online initiative, So Saw Law, which uses the two primary languages of the Kinh and Mông to provide legal information to Mông people on Facebook and, soon, TikTok.

Sơ said: “A lot of Mông people in my neighborhood are illiterate, yet they are rather good at using TikTok. Through the internet, young ladies in the northern mountainous region can make friends with someone in the southern region. Some girls had left the community to get married to strangers they met online.”

She noted that efforts to disseminate policies regarding forced and early marriage in ethnic communities have not been effective.

“Although the majority of ethnic people do not know Kinh language, local officers still use that language to disseminate the policy. They don’t understand what the officers say.

"A lot of ethnic people are unaware that they are breaking the law and do not even know what the death penalty is.

“I want to become a bridge between them and the law,” Sơ said.

Last year Sơ was one of two Vietnamese representatives to speak out against forced and under age marriage at an Asia-Pacific conference on child marriage in Nepal.

|

| Sùng Thị Sơ joins activities at an Asia-Pacific conference on child marriage in Nepal last year. |

Sơ said she wants to serve as a mentor for other girls in her village and to encourage them to pursue higher education.

"I want to show that women are just as capable as men at studying and working. I want to demonstrate to the parents in my village that education allows girls like me to make a lot of positive contributions to the community. They have no reason for stopping their daughters from continuing education.” — VNS