Economy

Economy

|

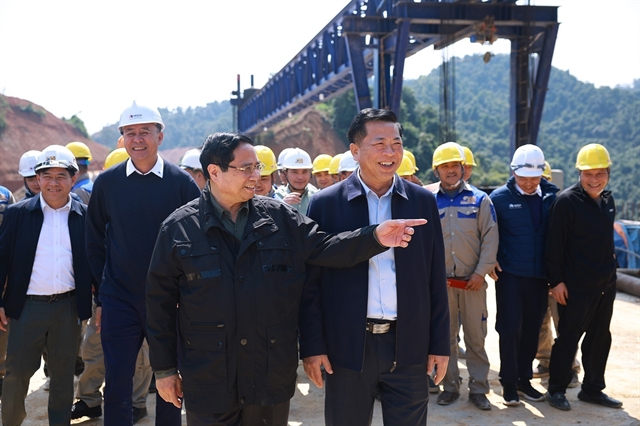

| Coal mining in Quảng Ninh Province. — VNA/VNS Photo Vũ Sinh |

Khánh Dương

HÀ NỘI — Việt Nam’s energy transition from coal power to renewable energy is anticipated to bring both opportunities and challenges to workers in the coal mining sector, experts say.

The coal industry, according to the International Labour Organization, is one of the industries set to experience the most significant decline in job demand due to the transition to sustainable energy. Mining of coal, lignite and peat extraction, as well as production of electricity using coal, is set to see a combined loss of 1.5 million jobs by 2030 worldwide.

In Việt Nam, there are currently up to 100,000 Vietnamese workers involved in the extraction of fossil fuels and the operation of coal power plants. Of these, approximately 78,000 are employed directly in the coal mining industry, while another 9,000 have been hired for positions in coal-fired power plants, according to an estimate by the Institute for Sustainable Futures in Australia.

Việt Nam’s labour structure is anticipated to change as a result of the energy transition in the country’s coal industry.

Vũ Đức Việt, a factory worker at Đông Triều Thermal Power Company under Việt Nam National Coal and Mineral Industries Group in Quảng Ninh Province, said workers approaching retirement age like him will not be affected so much by the country's energy transition.

“Young workers at power plants that are forced to shut down because of old equipment and low efficiency run the risk of losing their jobs, which would reduce their income and have an impact on their family's economy, family life and social life. Social instability is brought on by this,” he said.

Workers have to find new jobs, change careers and have to retrain to adapt to new jobs. They may find themselves struggling to acquire new knowledge due to inertia for working at the old plants for such a long time, Việt said.

Deputy director of Đông Triều Thermal Power Company Nguyễn Đức Sơn, said "With the life of the thermal power plant being about 30 years, after about 19 years, the workers will face the risk of unemployment because Việt Nam is currently limiting thermal power projects. The priority on renewable energy will create fierce competition in the electricity market.

“The plant will face the risk of having to reduce capacity, which means reducing revenue and profits and then, as a direct result, the income of workers will also be affected,” he added.

Workers are confronted with the requirements of improving their qualifications and skills to be able to adapt to different jobs in case coal-fired thermal power is phased out, he said.

The growth plan for Việt Nam’s coal industry is that domestic mining output will not actually decrease and may even increase compared to the present.

Mining output in 2022, 2023 and forecast for 2024 has been 44 million, 45 million and nearly 38 million tonnes respectively, according to the Việt Nam's coal industry development strategy.

But that mining will only focus on coal mines which have high economic value, use modern mining technology and applys mechanisation and automation.

Senior advisor of International Climate Initiative Just Energy Transition global project under the GIZ Energy Support Programme Vũ Chi Mai, said the Vietnamese coal industry will shift from traditional mining to activities with higher added value, such as deep processing and related services, requiring a higher-quality workforce.

“The coal industry's labour force in Việt Nam will tend to decrease in quantity but increase in quality, in line with the trends of energy transition and sustainable development,” she told Việt Nam News.

|

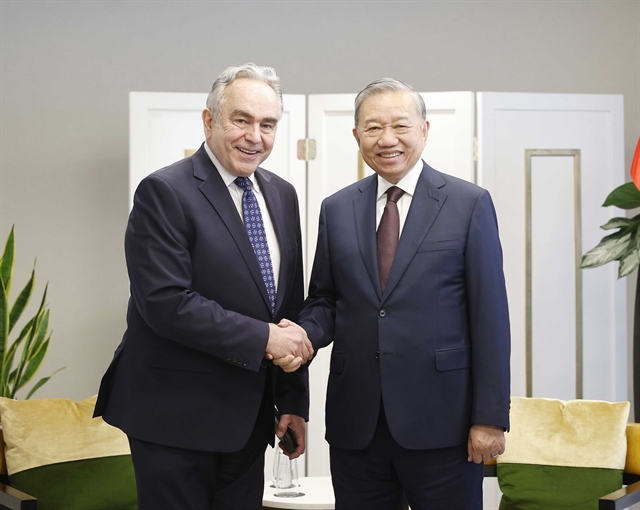

| A miner of Việt Nam National Coal and Mineral Industries Group in Quảng Ninh Province. — VNA/VNS Photo Trần Quốc Việt |

About 78,000 miners, who make up the majority of the current low-skilled workforce, will be the first group at risk of losing their jobs. They are the underground coal mining workforce, open-pit mining operators, technical workers operating mining equipment and supporting screening and maintenance of coal transport equipment. Quảng Ninh Province, home to 90 per cent of the country's coal production, will need to prepare for a major change in the labour structure, Mai said.

The coal mining workers might be transferred to mining restoration projects, such as afforestation, land regeneration, or development of industrial and service zones on the old infrastructure. Some others also need to be retrained to enter industries such as logistics, industrial equipment manufacturing or services, she said.

“The closure or reduction of 26 operating coal-fired thermal power plants and some new plants will have a strong impact on the direct workforce, such as technicians, operators, maintenance workers and managers,” she said.

Older or less-skilled workers in the coal power industry will have difficulty accessing retraining programmes or moving to new jobs. Differences in skills and job requirements in the renewable energy industry may render some workers underqualified, she said.

Related supporting industries such as coal mining, coal transportation, or mechanical equipment manufacturing factories will also be affected by the decrease in demand in the coal power industry. More broadly, areas such as Quảng Ninh Province, which are heavily dependent on the coal and coal-fired power industry, will face the risk of a decline in the local economy and employment, Mai said.

The shift from coal, however, will bring huge opportunities to skilled workforce.

Mai said the application of modern technology in coal mining and processing requires highly qualified human resources, especially mining engineers, experts in automation and environmental management, advanced mining equipment operation, clean coal processing and occupational safety management. The current young workforce can take on those roles, improve their knowledge to keep up with trends and demands.

If Việt Nam's coal industry growth plan is properly carried out, it will lessen adverse effects on the workforce and produce future workers who are more adaptable and of higher quality, she said.

The growth of new energy sectors is expected to create a great demand for labour, from design, installation, operation to maintenance. The transition to clean energy can bring better working conditions and income to workforce from coal-fired power plants, she said.

Timon Wehnert, an expert from Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy told Việt Nam News that this has been seen in Germany, where the coal sector employed 20,000 in 2016 and which will see these numbers fall significantly as the government plans to phase-out coal by 2030.

“During this time, a large number of coal workers will be retired, others will find jobs in the energy sector and most will even stay in the same company, now working on renewables or electricity grids.”

Currently, the big challenge for Germany is not unemployment, but a lack of skilled labour in some sectors and regions. Thus, public support programmes increasingly aim at supporting coal regions more broadly, Timon said.

Beyond creating jobs in the regions, the challenge is how to make the region attractive for high skilled labour to stay in the region or to relocate in. Factors like good schools, a healthy environment, cultural activities and general attractiveness of the region become more and more important, he said.

Female coal miners must be cared

According to coal miners in Quảng Ninh Province, female workers will face more risks than men because they have to take on the responsibility of raising children and taking care of housework. Participating in training courses will be more difficult to women than men and they must be healthy to be suitable for the new job.

Private companies and businesses tend to prefer male workers because of the issue of maternity and sick leave for female workers.

Timon said in many countries, coal miners are dominantly men. Consequently, support programmes often focus on the male miners. However, women often are also strongly impacted. For example, they may need to compensate for household income if the men lose their jobs.

In many regions, women have jobs, which are in support industries but not in mining itself, for example, providing food or other services to miners and those jobs would also be lost if mines close, he said.

Emphasising that training and education is paramount, he noted that it is necessary to actively look for impacts of coal phase-out and mine closures specifically on women. One way to do so is to include them in participatory planning processes in mining regions. — VNS

.jpg)