Politics & Law

Politics & Law

|

| Elected deputies attend the first session of the First National Assembly at the Hanoi Opera House on March 2, 1946. — Photo daibieunhandan.vn |

Compiled by Lê Việt Dũng

On January 6, 1946, voters across Việt Nam went to the polls to elect the country’s first National Assembly, a landmark step that came less than four months after independence was declared in Hà Nội on September 2, 1945 and amid severe political, economic and security challenges.

The election was not merely an administrative exercise but a central component of how the new state sought to establish legal authority and national representation at a critical historical juncture.

From independence to institution-building

On September 3, 1945, one day after independence was proclaimed, Hồ Chí Minh proposed that the provisional government formed after the August Revolution organise a general election “as soon as possible,” based on universal suffrage.

The proposed framework granted all citizens aged 18 and over, men and women alike, the right to vote and to stand for election, regardless of wealth, religion or social background.

In the weeks that followed, a series of decrees were issued to translate this proposal into law.

Decree 14 formally called for a general election to elect a National Assembly. Subsequent decrees established an election committee, defined voting procedures and specified that the election would be conducted on three core principles: universal suffrage, direct voting and secret ballots.

Article 2 of the October 1945 election decree stated that all Vietnamese citizens aged 18 and over had the right to vote and run for office, except those deemed mentally incapacitated or deprived of citizenship rights.

The election was initially scheduled for December 23, 1945 but was postponed to January 6, 1946. The delay was officially attributed to the need for additional preparation time and to facilitate broader political participation in a context of national reconciliation.

Election committees were established at multiple administrative levels, down to villages and communes. Voter rolls and candidate lists were compiled and publicly posted. Candidates entered the race either by volunteering or through nomination by local groups.

The election took place nationwide on January 6, 1946, including in regions affected by armed conflict. According to official figures, voter turnout reached 89 per cent nationwide.

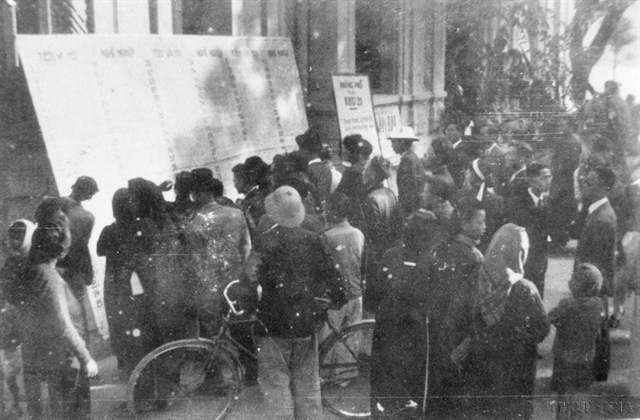

|

| Voters in Hà Nội view the names and biographical details of National Assembly candidates. — VNA/VNS Photo |

In Hà Nội, participation was reported at approximately 92 per cent across 74 inner-city wards and 118 suburban villages. Hồ Chí Minh was elected in the capital with 98.4 per cent of the vote.

The election resulted in a 333-member National Assembly. Official data indicated that 57 per cent of elected deputies were affiliated with various political parties, while 43 per cent were non-party representatives.

The National Assembly included 10 women and 34 representatives of ethnic minority groups, with members drawn from all three regions: north, central and south. By occupational background, 87 per cent were workers, peasants and revolutionary fighters.

The First National Assembly convened its inaugural session on March 2, 1946 and appointed Hồ Chí Minh as the President of the Democratic Republic of Việt Nam. It also began drafting a constitution.

The Constitution of 1946, adopted later that year, defined Việt Nam as a democratic republic and affirmed that all State power belonged to the people. It also codified a range of civil and political rights, including gender equality, explicitly stating that women and men were equal in all respects.

From a legal perspective, the Constitution completed the transition from provisional governance to a formal state structure with a legislature, an executive and a constitutional framework.

International context

The 1946 election took place during a period of global political reconfiguration following World War II, as many countries were rebuilding institutions, redefining political systems or expanding the franchise.

In much of the world, universal suffrage was still a newly-achieved success, unevenly applied or constrained by legal and social barriers related to gender, race, property or education.

In France, women voted in national elections for the first time in October 1945, following a decision by the provisional government a year earlier.

The election of a Constituent Assembly marked a major democratic step after years of occupation, but it also underscored how full suffrage had been achieved even in long-established European republics.

Japan’s April 1946 general election similarly represented a break with the past. Conducted under Allied occupation, it was the first election in which Japanese women were allowed to vote and stand for office, following revisions to the election law in late 1945.

More than 13 million women participated and 39 were elected to the lower house, an outcome widely regarded as exceptional at the time.

In Italy, the June 1946 referendum that abolished the monarchy and established the republic was also the first national vote to include women. Italian women had only gained voting rights at the local level earlier that year and their participation at the national level was still a new and evolving development.

In the UK and the US, universal suffrage existed in law by the mid-1940s but limitations remained in practice. In Britain, plural voting, allowing some individuals to cast more than one ballot based on property ownership or university affiliation, was not abolished until 1948.

In the US, racial discrimination, particularly in southern states, continued to restrict access to the ballot through poll taxes, literacy tests and other legal mechanisms, despite formal constitutional guarantees.

|

| A female voter in suburban Hà Nội casts her ballot on January 6, 1946. — VNA/VNS Photo |

Against this backdrop, Việt Nam’s 1946 election framework stood out for its breadth. The voting age was set at 18, lower than the prevailing standard in many countries at the time, where eligibility commonly began at 20 or 21.

The legal provisions imposed no requirements related to property ownership, tax status or educational attainment, an important distinction in a society where illiteracy and poverty were widespread.

The framework also explicitly granted women equal rights to vote and stand for election nationwide from the outset, rather than through gradual or partial extensions.

In addition, it made no legal distinctions based on ethnicity or religion, extending the franchise across the entire territory and to all recognised population groups.

In comparative terms, the absence of barriers related to gender, wealth and education placed Việt Nam’s electoral framework broadly in line with, and in some respects ahead of, contemporaneous developments in many post-war developed countries.

Function and legacy

Beyond representation, the election served a strategic political function. Internationally, it provided the new government with undeniable legal legitimacy.

A government backed by an elected assembly could present itself as the representative authority of the Vietnamese people in diplomatic negotiations, including those that led to the preliminary agreement with France on March 6, 1946.

Domestically, the election offered a framework for participation that cut across regional, social and religious lines. By bringing different groups into a single legislative body, the State sought to promote national unity by integrating diverse interests within a common institutional framework.

|

| The government of the Democratic Republic of Việt Nam elected by the First National Assembly. — VNA/VNS Photo |

Within months, negotiations with France collapsed and full-scale war followed. Nonetheless, the election marked a pivotal moment in the country’s early State-building process.

It established the National Assembly as a central institution, produced Việt Nam’s first constitution and articulated a vision of citizenship based on broad participation. In historical accounts, the election is often cited as the point at which revolutionary authority was translated into a constitutional framework.

Eighty years later, the vote continues to be referenced as a foundational episode in Việt Nam’s political history, an early effort to define legitimacy, representation and sovereignty through electoral means during a period of profound uncertainty. — VNS