Sunday/Weekend

Sunday/Weekend

|

| Today Phnom Penh is a vibrant city with more than 2 million people and one of the top travel destinations in Southeast Asia. VNS Photos Nguyễn Vân Hậu |

by Nguyễn Vân Hậu*

Nearly half a century had passed until I planned myself a trip to the old battlefield, where I spent part of my youth and where numerous memories still race through my mind today. As our coach ran smoothly on Cambodia's National Highway heading to Phnom Penh, my mind bounced back to what was going on 45 years ago on this very land.

After April 30, 1975, when South Việt Nam was liberated and our country was reunified, we all thought that we would never have to go through war again. We were young and hopeful, and didn't even have time to make our youthful dreams come true, as once again, we had to drop our pens and pick up our rifles to follow our forefathers and venture out to the battlefield to protect our country.

We didn't know then that between 1975 to 1978, along the southwestern border with Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, under the leadership of Pol Pot, had launched multiple surprise cross-border attacks on Việt Nam, killing many innocent people and destroying many villages.

Việt Nam had just put an end to its 20-year-long war. We only wanted peace to rebuild our war-torn country. The Vietnamese leadership only wanted to protect our border, trying to find peaceful solutions to these provocative actions, but the Khmer Rouge rejected them all.

Việt Nam had filed numerous complaints to the United Nations and called on its peacekeeping force to step in to stop the Khmer Rouge's bloody cross-border raids. But the UN, as well as world powers kept silent and Việt Nam's cries for help went unheard.

We had no choice other than to make use of force to save our own people, and protect the country and its territories according to Article 51 of the UN Charter.

In response to the official appeal of the United Front for National Salvation of Kampuchea (UFNSK) who asked Việt Nam for help, the Việt Nam People's Army launched a large-scale military campaign to drive the Khmer Rouge forces back to their border to protect Việt Nam's territory. Furthermore, the Vietnamese Volunteer Army assisted the Cambodian patriotic force to topple the Khmer Rouge rule and liberate the entire Cambodia from the genocidal regime.

|

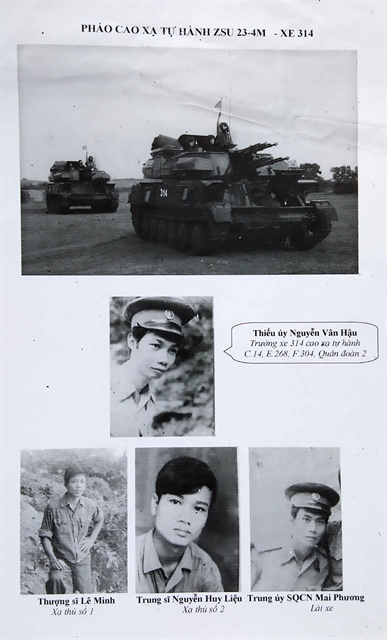

| Second Lieutenant Nguyễn Vân Hậu, chief of the self-propelled anti-aircraft battery No. 314 with his comrades Sergeant Major Lê Minh, Sergeant Nguyễn Huy Liệu and driver Lieutenant Mai Phương. |

Crime against humanity

The Khmer Rouge was a regime that ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979 by western-educated top leaders including Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, leng Sary and Khieu Samphan. During their four years of ruling Cambodia, they killed nearly 2 million Cambodians, including many of Vietnamese origin.

Their hatred foreign policy targeted Việt Nam with military raids, arrested and killed thousands of Vietnamese people on Phú Quốc and Thổ Chu islands and all along the southwestern border between the two countries.

The worst of these series of attacks was a massacre of 3,157 people in April 1978 in Ba Chúc Commune, known today as Ba Chúc Town in Tri Tôn District, An Giang Province. During their 12-day raid the Khmer Rouge troops occupied the commune and they carried out unimaginable crimes against humans, using horrifying methods to torture and slowly kill people. Many people, mostly women, children and the elderly, that had sought refuge in Phi Lai and Tam Bửu pagodas were also arrested and killed.

When we arrived at Ba Chúc in January 1979, upon seeing the blood stains on the pagodas' walls, I felt my heart skip a beat, wishing we had arrived earlier and not let our fellow countrymen die so tragically.

|

| Mộc Bài international checkpoint on the Việt Nam-Cambodia border. Photo Nguyễn Vân Hậu |

We drove on Cambodia's National Highway 1 from Vietnamese Mộc Bài border checkpoint to Phnom Penh, about a 170km journey. We crossed the Mekong River at Neak Leung Bridge on a trans-Asian highway, vital for trade between our two countries. Neak Leung is Cambodia's beautiful and longest cable-stayed bridge inaugurated in 2015, 90km from Mộc Bài.

Forty-five years ago, from January 1st-5th, 1979, Việt Nam's volunteer armymen and soldiers of the Kampuchean United Front fought together in a joint battle to win back the strategic port of Neak Luong in Svay Riêng Province in Cambodia.

On January 6, 1979, the first groups of the 7th Division of Vietnamese army volunteers and a Kampuchean United Front battalion captured the east side of the ferry port. During that night, Vietnamese sappers set up a floating bridge; landing crafts and amphibious battle vehicles carried the infantrymen across the river to capture the west side of the port to clear the path for the next day.

On the next day, our great army including infantry, tanks and artillery battalions all crossed the Mekong to liberate Phnom Penh. Looking back, it took us only seven days since we advanced from Tây Ninh to arrive in Phnom Penh.

The Khmer Rouge forces ran away hiding near the border with Thailand, and still aided and abetted by some countries to continue their war.

On January 7, 1979, the capital Phnom Penh was liberated. The next day, the People's Republic of Kampuchea was formed with Heng Samrin as President, closing the most painful chapter of the Angkor land history.

Trip back in time

|

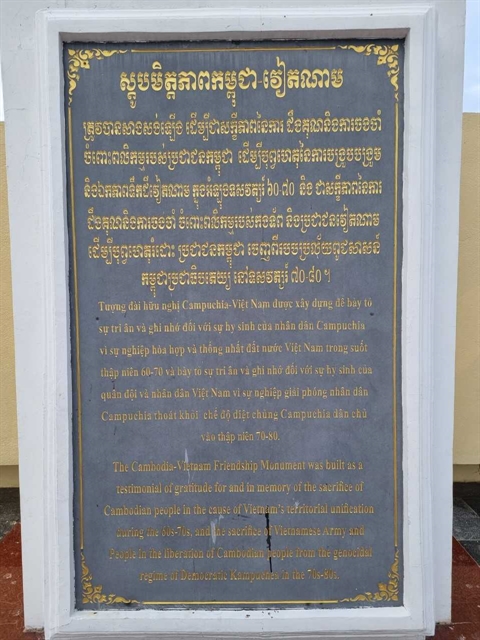

| The plaque at a Việt Nam-Cambodia Friendship Monument commemorating the mutual sacrifices made by the people of both countries to ensure lasting peace. Photo Nguyễn Vân Hậu |

A trip without preparation means that you have prepared for failure. Not all trips to Cambodia would take me to where I wanted.

I chose the four-day tour that led me to Sihanoukville, and closer to the destinations closest to my heart. It was here I stepped all those years ago and shed some blood in a minor injury I suffered during the fierce battles fighting the Khmer Rouge.

Names of Phnom Penh, Kampot Town, Bokor Highlands and the beach town of Sihanoukville, only 20km away from the military port of Ream were the places we passed through 45 years ago.

I had Googled them all and my heart skipped a beat when I found the roads, the stops, hamlets and villages where we used to fight, station, or march through. I worked on my itinerary, having to miss out some remote destinations in the forest. A careful plan that would take only four hours to complete was ready for me to revisit, and I would bring it up with our tour guide during the trip.

Travel companies would not allow tourists to stray too far away from the registered itineraries for visitors' safety, but our guide said my "plan to escape" for four hours was within reach and he helped out.

Valuable visitors

After the war I left the army, like many fellows of my generation, I didn't have a job, let alone a good career. I eventually found myself in the South where I was swept away with work, setting up a family, raising our children. We rarely met with our former friends from the battalion that had stayed in my home province of Quảng Trị or elsewhere in the North.

Many attempts to team up with former comrades-in-arms in my battalion ended in failure so I decided to undertake this journey with my spouse as my only companion. We checked our passports at the Mộc Bài/Bavet checkpoint in Tây Ninh/Prayveng without delay and our guide told us: "Cambodia treats Vietnamese passport holders as VIP guests!"

Mộc Bài was a busy border checkpoint with people and vehicles passing through. When border guards in Cambodia saw our passports, they let us pass without any delay, which made me believe our guide was right.

On further research, I found out that according to Cambodia's Ministry of Tourism, Việt Nam is a stable tourism market with a lot of potential. In 2022, Việt Nam topped the list of visitors to Cambodia, followed by Thailand and China. In the 10th month of 2023, more than 880,000 Vietnamese visited Cambodia and 300,000 Cambodians came to Việt Nam.

To date, Việt Nam ranks the third biggest commercial partner of Cambodia behind China and the United States. Among ASEAN countries, Việt Nam is Cambodia's biggest trade partner and with more than 200 investment projects with registered capital nearing US$3 billion, it is the top five biggest investor in Cambodia.

Legacy of peace

|

| Today, Việt Nam ranks in the top five international investors in Cambodia with more than 200 registered projects worth US$3 billion. VNS Photo Nguyễn Vân Hậu |

In 1989, Việt Nam withdrew all of its volunteer troops, leaving behind the immense heritage for the Cambodian people: the complete fall of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and well-rooted peace for development.

Cambodia's former King Norodom Sihanouk said: "If Việt Nam didn't stop Pol Pot, all of the Cambodian people could have perished." In the King's royal family, nearly 20 people, including his children and grandchildren were taken away from Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge, killed or simply vanished.

When we stepped into the Toul Sleng Museum in Phnom Penh, I couldn't keep my eyes on the remnants of the Pol Pot regime's horrors for too long. They were too horrifying. The hairs on the back of my neck stood up as I thought about the crimes carried out by the regime.

Former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen was quoted as saying: "When Cambodian people went to the brink of death, they were only praying for Buddha to save their lives, then Vietnamese volunteer soldiers appeared and saved them. Cambodians called the soldiers, 'Buddha's army'."

Forty years later, in 2018, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), commonly known as the Cambodia Tribunal or Khmer Rouge Tribunal, a hybrid court between the Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations provided justice to the Cambodian people, who were victims of the Khmer Rouge crimes.

The ECCC found serious violations of Cambodian penal law, international humanitarian law and customs including crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979.

Two former Khmer Rouge leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were sentenced to life in prison, Ta Mok and Ieng Sary had died before the court's verdicts. Pol Pot had died before he could be brought to this court to face charges of the crime of genocide.

These court rulings, though late, provided justice and righteousness for the people of Việt Nam, and for us, the volunteer soldiers.

Monument of friendship

|

| Veteran Nguyễn Vân Hậu at the Việt Nam-Cambodia Friendship Monument in Phnom Penh on a recent visit. Photo Nguyễn Vân Hậu |

After less than seven hours, our coach arrived in Phnom Penh, a beautiful and hospitable city of more than 2 million people, one of the rapid growing metropolis in Asia. The city today is a sharp contrast with what I saw 45 years ago. It was then a literally dead city under the Khmer Rouge rule.

I have been to various war memorials around the world, but when I stood in front of the Việt Nam-Cambodia Friendship Monument, it was hard to describe the surge of feelings in my heart and soul.

The monument stands tall in the central square of Phnom Penh, a symbol of the brotherly friendship between the peoples of Cambodia and Việt Nam. It is recognition by the Cambodian people for the sacrifices of Vietnamese volunteer soldiers, who shed their blood to help fellow Cambodians break free from the genocidal crimes by the Khmer Rouge. More than 20 similar monuments had been built across Cambodia, I was told.

I bowed my head to thank the people of the Angkor land, who didn't forget the sacrifices of hundreds of thousands of my comrades-in-arms and had not forgotten us, the soldiers. It is enough that we are in their thoughts and we ask for no more.

We would also like to say that with all the certificates of merit, army-exploit orders and the International Duty awards we received, we also bought frames to respectfully display them.

We only value precious peace and justice. These are the foundation of our friendship that both of us should hold dear to our hearts and nurture for all of eternity.

My time in Phnom Penh comes to an end and as I left the Friendship Monument, birds flock to the memorial. They rested on the sculpture of a Vietnamese army volunteer standing shoulder to shoulder with a Cambodian companion-in-arms. I lingered back to glance my eyes up to the sky, and in my mind bid farewell to the souls of my comrades, whose presence I could feel, gathered here in the cool afternoon breeze. VNS

*Nguyễn Vân Hậu, second lieutenant, Company 4, Battalion 1, Regiment 9, Division 304 of the Vietnamese Volunteer Army fighting to liberate Cambodia from the Khmer Rouge regime. In early March 1979, he was dispatched to fight the northern border war in Lạng Sơn. In 1981, Hậu was chief of the self-propelled artillery battery No 314. He later demobbed to work in a government office. He graduated from Hồ Chí Minh City's Economics College, had a postgraduate degree at the National University of Administration, and was a guest lecturer at the College for Administration and Public Affairs in Lâm Đồng Province. He is now retired and recently visited Cambodia as a tourist.