Society

Society

Trịnh Thu Thanh and Nguyễn Thị Hằng, two researchers from the National Centre for Special Education Research under the Việt Nam National Institute of Educational Sciences, have been given an award for the best project of the "knowledge for education" programme, for developing made-in-Việt Nam tactile books for visually impaired children.

|

| Children with visual impairments read a tactile book from the team at Nguyễn Đình Chiều School, a school for children with visual impairments, in Hà Nội. — Photo thanhnienviet.vn |

HÀ NỘI — Trịnh Thu Thanh and Nguyễn Thị Hằng, two researchers from the National Centre for Special Education Research under the Việt Nam National Institute of Educational Sciences, have been given an award for the best project of the "knowledge for education" programme, for developing made-in-Việt Nam tactile books for visually impaired children.

The programme was co-organised by the Ministry of Education and Training and the Central Committee of the Hồ Chí Minh Communist Youth Union.

Thanh said normal children are familiar with books from a very young age, helping them prepare for learning how to read.

Children with visual impairments also need to be familiar with tactile books to help develop skills, thereby being ready to learn Braille, she said.

“There were no made-in-Việt Nam tactile books until us, so blind children have to begin to learn how to read Braille without having experience with tactile books,” she said.

“Without these experiences, children lack the discovery and joy of reading,” she said.

Thanh and Hằng, with the support of Louise France, a British expert, who has 20 years of experience teaching children with visual impairments in the United Kingdoms, have researched and developed made-in-Việt Nam tactile books for children with visual impairments with the hope to provide them with a tool to practice tactile skills to learn Braille more easily.

Tactile books

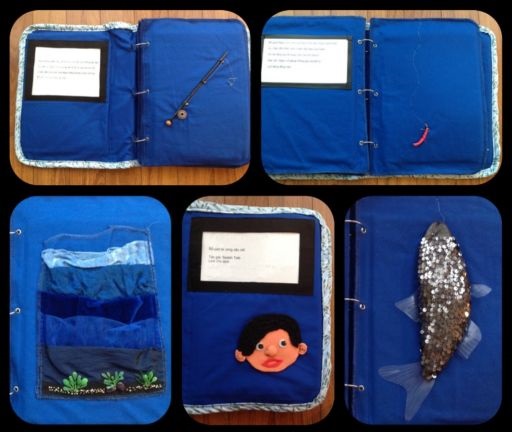

Tactile books, having five to 10 pages, are specially designed and completely handmade on thick canvas or cardboard, she said.

They are designed with small objects and patterns attached to fabric pages, creating images, which can be felt by touch. The tactile pages have both printed and Braille text so that normal people could also read, she said.

The book is divided into four levels; A, B, C, D.

Level A is the easiest level, with tactile books using real objects attached to the pages of the book, along with familiar tunes for visually impaired children to touch and feel.

At level B, books present poems and stories, using simple tactile pictures and models. At level C, books present simple stories, using complex tactile pictures. At this level, the images have more complex symbols such as trees and motorbikes.

The most difficult is level D, the books present stories about the world outside the child's experience, using complex tactile pictures.

Children's books have to be suitable for children's psychology at all ages, Thanh said.

The team wrote their own stories or adapted them from published children's stories. For the adaptation, the team had to contact the author for permission. When adapting content to fit tactile books, the consent of the writers must also be obtained, she said.

Thanh said making a tactile book is difficult because, in addition to the story, it needs also images sewn onto the pages.

Visually impaired children will read books by touch. The more developed the child's touching skills, the greater the ability to visualise to understand the story and the messages from life through the pages of the book, she said.

Therefore, Thanh and her teammates had to spend many years researching to understand the levels of touch ability of visually impaired children, thereby designing different books for children of different levels.

"Before us, no one in Việt Nam has researched and made tactile books, so relevant documents were not available in Vietnamese,” she said.

They had to research by foreign documents, she said.

|

| A tactile book made by the team.— Photo thanhnienviet.vn |

Seeking support

After five years of research, experimentation and making the books, Thanh’s team and volunteers have only made 50 tactile books, partly because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, making a tactile book requires meticulousness so they could not make them fast.

Normally, they need two weeks to make a tactile book, she said.

Thanh and her teammates have contacted a number of deaf people to hire to sew pictures for the books.

Thanh said deaf people are very skilful, so, they can help to make the tactile books faster.

After finishing the books, Thanh needed the first evaluation, so she contacted parents whose children are visually impaired, to send them books for the children to use and make assessments.

At first, some parents were not keen, but the team never gave up.

“We persuaded them day after day,” she said.

Then, parents who witnessed their children reading the tactile books and changing every day started to think differently and began enthusiastically supporting the team, she said.

Thanh said she and her team have planned to establish a library of tactile books for children with visual impairments this year.

The library will have a space for children with visual impairments to read on site. Children can also borrow books to read at home, she said.

Moreover, Thanh said she and her team also wrote detailed instructions on how to make a tactile book so that schools for children with visual impairments can make their own books for their students.

Associate Professor Nguyễn Xuân Thành, head of the Secondary Education Department under the Ministry of Education and Training told Tuổi trẻ (Youth) newspaper that he highly appreciates the idea of making the first made-in-Việt Nam tactile books for children with visual impairments.

Thành also praised the way that the team provided instructions on how to make a tactile book, so that schools for children with visual impairments can make their own books for their students. — VNS