Life & Style

Life & Style

.jpg)

|

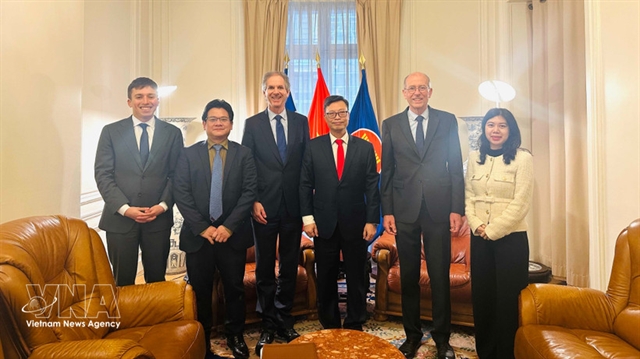

| Filmmaker Lê Văn Kiệt at Bride of The Covenant launching. Photo vov.vn |

HÀ NỘI — Film director Lê Văn Kiệt, a graduate of the University of California’s Theatre and Television Department, has been making waves both at home and abroad. His Hollywood film The Princess was screened at the inaugural Culture of the World Festival in Hà Nội last weekend, drawing attention for its storytelling and production quality.

Kiệt’s latest work, Khế Ước Bán Dâu (Bride of the Covenant), is now showing in cinemas across the nation. The horror film has also been selected for screening in the Midnight Passion section at the Busan International Film Festival, showcasing his growing international reputation.

Kiệt spoke about the making of Bride of the Covenant, highlighting his creative process and dedication to bringing Vietnamese stories to a global audience.

Bride of the Covenant is your return to the horror genre. What inspired you to choose this script and make it?

I didn’t set out to return to the horror genre. But when reading the novel by Thục Linh, I felt it presented a very special and beautiful world, especially one rooted in Vietnamese traditional culture, a niche I had never explored before.

The story in the film coincidentally touched on my own memories. I remember my grandmother telling me about her marriage, a long journey to her husband's house carrying worries and hope as she entered a completely unfamiliar family.

Images that once seemed distant now appear clearly, almost reflected in every opening frame of the film, from the wedding procession to character Nhài's hesitant steps across the threshold of her husband's house.

This time, I did not emphasise the horror element, but I wanted to bring community memories into the film.

When adapting the novel, what elements did you retain and change to make the work suitable for cinematic language?

I set myself a moderate limit when making the film because the novel's world is so large and layered with meaning. In the novel, each character has their own life: from the sons of the Vũ family to each daughter-in-law and housekeeper, all intertwined into a complex picture, both mysterious and colourful.

But cinema is different. It requires concentration and a consistent emotional journey for the audience. If the audience takes on everything, the story becomes scattered, making it difficult for them to stay emotionally engaged until the end.

I chose Nhài as the central character who can transmit the spirit of the work. Through her journey, the audience not only feels the bondage of an unjust covenant, but also sees the loneliness, longing and cultural aftershocks deeply embedded in the memory of the Vietnamese people.

The movie is a period drama with folk rituals. How did you put Vietnamese folk culture in the film to attract the audience?

The film's setting is a fantasy space from the 17th to the early 19th century. It is not too unfamiliar for the audience to connect with. While rare on the big screen, these settings are more common in television series.

The film was shot in the north, and the crew chose locations that retained their mossy atmosphere while avoiding modernisation. The makeup and costume team, the young people with a deep understanding of history, worked hard to create a complete ensemble that preserves and respects traditional culture while opening a creative space for cinema.

With period dramas, I always focus on respecting cultural and historical details. For example, scenes involving rituals, cooking or interactions with the mother-in-law contain small but significant elements of Vietnamese culture. We carefully research every detail to ensure both accuracy and naturalness.

This is not just for filming, but to allow the audience to feel authenticity and appreciate the beauty of traditional culture.

The film was presented in the Busan International Film Festival's Midnight Passion section as a representative of Vietnamese horror. How do you feel?

I had brought Gentle to the festival before, so I was familiar with its openness to new voices in Asian cinema. It is great that Bride of the Covenant is competing in the Midnight Passion category.

This category is reserved for horror and thriller films. The presence of a Vietnamese film at the festival is not only a personal joy but also a strong signal for Vietnamese cinema. It shows that our work is not marginalised, but trusted internationally.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the crew. They faced challenges in production, funding and communication. Their perseverance and never-give-up spirit made the film possible. For me, this recognition is for all of us.

You have made both art-house and box-office films. How do you balance them?

I used to think I had to choose one clear path, either art-house or box office. But after more than 10 years of filmmaking, I realised there is no need to deny or affirm anything absolutely. The important thing is to bring yourself, your core, into each project.

Genre is just a cover. Whether horror, action, romance or comedy, I focus on the character’s experience. I don’t see any conflict between commercial and artistic purposes, only more opportunities to tell a story in different ways.

How have you changed in mindset and filmmaking skill since the beginning?

The most obvious change is the way I tell stories. When I first started, I was still immature and had weaknesses, and in fact I still have much to learn. But after more than ten years of filmmaking, I realised Vietnamese cinema has progressed far beyond what I imagined. Mưa Đỏ (Red Rain) is an example, a revolutionary historical film that stands on par with international productions.

For me, each film is an opportunity to renew myself. House in the Alley is a horror, Gentle is a Gothic-style experiment in modern society, Hai Phượng is the first Vietnamese femail-led action film, and The Princess is a hybrid of John Wick and Sleeping Beauty.

Bride of the Covenant is my experiment with spiritual period drama, a genre rarely explored by Vietnamese filmmakers.

I don’t limit myself. As long as a story is interesting enough for the audience and offers experiences they have never had before, it motivates me to make films. — VNS

.jpg)