Society

Society

Some four million men in Viet Nam will have no chance of getting married by 2050 if the current imbalance in the nation’s sex ration persists, experts say.

|

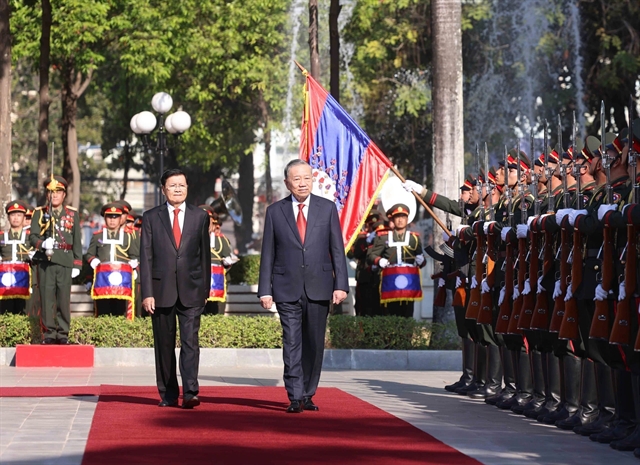

| The gender ratio at birth in Hà Nội remains skewed in favour of the boys as people stick to old conventions and beliefs. — VNA/VNS Photo |

HÀ NỘI — Some four million men in Việt Nam will have no chance of getting married by 2050 if the current imbalance in the nation’s sex ration persists, experts say.

According to the Hà Nội Population and Family Planning Department, the capital city’s boy-to-girl ratio at birth in the first 9 months of this year remained high at 113.6:100.

Seven districts with the highest boy-to-girl ratios at birth are Sơn Tây (131.9:100); Ứng Hòa (130.1:100); Mê Linh (123.6:100); Ba Vì (121.9:100), Phú Xuyên (121.3:100), Thạch Thất (120.9:100) and Sóc Sơn (120.3:100).

Similar imbalances nationwide will lead to a shortage of women, which means that by 2050, 2.3-4.3 million men in Việt Nam will have no chance of finding wives, the General Directorate of Population and Family Planning estimates.

Population experts have warned that the gender imbalance can lead to an increase in the trafficking of women and children, prostitution and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases like HIV/AIDS.

The imbalance in sex ratio at birth and a preference for sons has become a pressing issue in the country.

Since it is common practice that women go to live with their husbands’ family after getting married, the understanding is that daughters are eventually “lost” for good; hence, without a son, there will be no one to take care of parents when they get old.

With this mindset, couples come under a lot of pressure from the husbands’ families to have sons, and this increases if the first child is a girl.

Kiều Thị L. (first name withheld) in Sơn Tây Town’s Đường Lâm Commune, only succeeded in having a son from her 6th pregnancy. She gave birth to 3 daughters and had two intrauterine foetal deaths. Her husband was the head of his family line, the pressure to have a male child was immense.

Another couple in Ba Vì District’s Tây Đằng Commune gave birth to five children in hopes of getting a son. Three of them ended up being infected with the HIV virus from their father who was doing drugs.

Nguyễn Thị Liên, a family planning official in the commune, she visited the house repeatedly to persuade them to stop having babies, but the wife would sneak out every time she came.

“In more well-to-do families, their attitude towards family planning officials is, ‘I give birth to my children so I will raise them, keep your nose out of my business,’” Liên said.

Đỗ Việt Hùng, director of the Centre of Population and Family Planning in Sơn Tây town, said that the hard, exhausting labour required in the fields was the underlying reason for the preference for sons in suburban areas.

Moreover, as 70 per cent of the rural population do not get any pension from the State, they feel insecure about not having a son to look after them when they get old, according to Hùng.

Long-term effort

The preference for sons is so deep-rooted that several measures taken in recent years to tackle gender imbalance, including increasing awareness of family planning, are still facing several obstacles.

Nevertheless, Hùng said, more people should be informed of the consequences of gender imbalance, as well as of the Population Ordinance issued by the National Assembly Standing Committee in 2003, which forbids gender selection of foetuses.

Hoàng Đức Hạnh, deputy director of the Hà Nội Department of Health, said that even though a Government Decree No 114 issued in 2006 regulated penalties for couples that gave birth to the third child, these were only applicable to Party members, not other citizens.

Moreover, the decree was rendered void after the Decree No. 176 was issued in 2013. This regulated penalties for medical wrongdoing but not for couples having more than two children.

Hạnh said reducing gender imbalance is a long-term mission that needs the entire political system to get involved.

Family planning criteria should be integrated into common goals that all citizens agree to, like community conventions or the criteria for villages to be recognised as “cultural villages,” he said. — VNS