Features

Features

Thousands of elephants, tigers, panthers and other wild animals once roamed the jungles of Việt Nam. They are now crying for help. But are we listening?

|

| National heroes: Somewhere in the Central Highlands around 1963 as captured in a still frame by journalist Wilfred Burchett on a visit to the liberated zones of South Việt Nam. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

by George Burchett

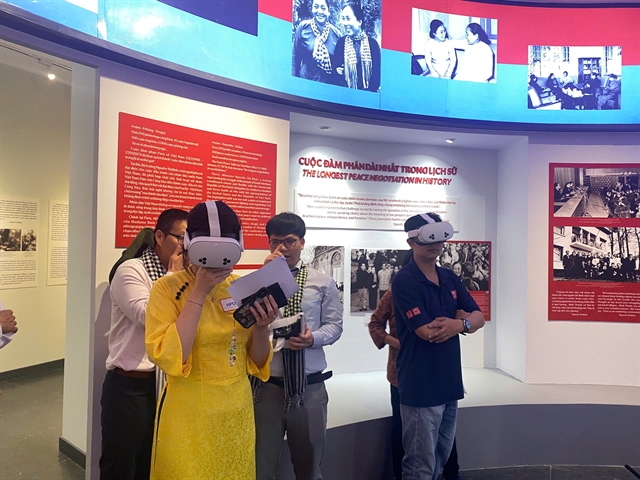

In April 2015, I was invited by the Cercle des Francophones (Francophone Association) of Hà Nội to present the film Loin du Vietnam (Far from Việt Nam) at the Hà Nội Cinémathèque. The film was made collectively in 1967 by some of the great names of new French cinéma: Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Agnès Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, in support of Việt Nam’s resistance to US aggression.

I was familiar with the film, but decided to do some extra research for the occasion.

Quite by chance, I stumbled upon the website of a film festival at Casa de Cinema at the Villa Borghese in Rome titled, Il vietnam e il cinema francese – Việt Nam and French Cinéma. One of the presented films was Wilfred Burchett in Việt Nam, France/Việt Nam, 1963, 44min.

Wilfred Burchett is my father, the Australian journalist, the first to visit the liberated zones of South Việt Nam (Việt Cộng controlled) in late 1963, early 1965.

I knew a film had been made of his visit but had never seen it and had never been able to track it down. And there it was, on the program of a film festival in Rome.

I e-mailed the organisers at Casa de Cinema, who put me in touch with the AAMOD (Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico) film archive in Rome. I contacted them and they kindly made the film available to me.

So I finally watched it for the first time in my life at home in Hà Nội. It was a highly emotional experience to watch the almost half-century-old black and white footage, first downloaded on my laptop, then on my TV screen.

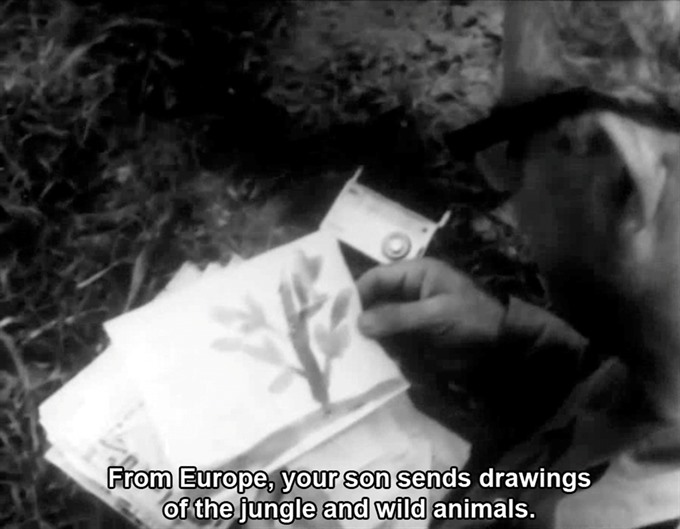

Eight minutes into the film, a VC postman delivers my father his mail. The commentary says:

"From Europe, your son sends drawings of the jungle and wild animals. He is a little afraid for you, but he doesn’t yet know that here the most dangerous animals are American imperialists."

Well, that son is me, artist George Burchett. Yes, these were my drawings "of the jungle and wild animals", inspired by the letters my father sent my brother, sister and me – then living in Moscow – in which he explained why he was away for so long. To make it more interesting for us, he told stories of tigers, elephants, monkeys and other exotic creatures from the jungles of South Việt Nam.

|

| Jungle stories: Mail delivery somewhere in the jungles of South Vietnam. Still photo of journalist Wilfred Burchett on a visit to the liberated zones of South Việt Nam,1963-64. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

Motorised cavalry

Sixteen minutes into the film, my father crosses a river on horseback – very heroic-looking, like Indiana Jones – and suddenly this extraordinary panorama fills the screen. The narration says:

"After an arduous journey you are now in the Central Highlands.

Have you ever seen so many elephants?

Did you know they are the heavy motorised cavalry of the local guerillas?"

Extraordinary. Like some lost world suddenly re-discovered. When this scene was filmed, thousands of elephants, tigers, panthers and other wild animals roamed the jungles of South Việt Nam. Elephants played a special role.

From my father’s letters from the jungles of South Việt Nam:

"There are lots of tigers and elephants; lots of deer and wild pigs around where I am. I found out lots of interesting things about elephants and the more I hear about these animals, the more I like them. They are very, very intelligent and very sensitive. They worry about things just like human beings. I heard of one the other day who loved his master very much. They had worked together in the forest for many years together, the elephant pulling the trees away from the land being cleared for cultivation and afterwards, carrying the grain and master together back to the village. The master got quite old and died and the elephant wept and was very unhappy. For a whole week he would not eat and then he died.

The elephant becomes very affectionate towards everyone in the family with whom he works. If there are some big rows, between Mummy and Daddy for instance, or between Annichka and George, the elephant simply cannot stand it. He stalks off, deep into the forest and someone must go after him, blowing a certain note on a buffalo horn, and then talk to him nicely and explain that there will be no more quarrelling. Then he agrees to come back."

My father’s words merged with the scene of elephants in the shimmering water. It took a long time for this image to reach me, and it reached me in a strange, round-about way. So I invite you, who read this, to look at it very carefully. I’ve counted about 60 elephants, each with a man riding it.

Verge of extinction

There are about 60 wild elephants left in Việt Nam today. Not in one big group like in the image I am sharing with you, but scattered around the few remaining wilderness areas of Việt Nam. Another 100 or so lead a miserable existence carrying tourists, mostly in Đắk Lắk Province in the Central Highlands. These figures are provided by Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. And they are dire. The number of wild elephants in Việt Nam is unsustainable and the elephants are on the verge of extinction. Yes, extinction.

What bombs and defoliants could not accomplish, modern man is on the verge of achieving: the total elimination of elephants in Việt Nam. The main causes are deforestation and loss of habitat, man-elephant conflict, poaching. Elephants do not reproduce in captivity. Those who die from exhaustion, malnutrition or disease cannot be replaced. So domestic elephants are also doomed.

Elephants have played an important role in Việt Nam’s long history of resisting invaders. Elephants carried the Trưng Sisters into battle against the Chinese invaders. The virgin lady warrior Bà Triệu also rode an elephant into battle. As did many other great Vietnamese heroes. And elephants were the "heavy motorised cavalry" at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ during the war of resistance against French colonialism and in the jungles of Central and South Việt Nam during the war of resistance against US imperialism. They should be treated like national heroes, with the respect due to war veterans.

Saving the elephants of Việt Nam should be a national duty and a matter of national pride. Elephants, tigers, rhinos and many other species are being hunted and exterminated to satisfy man’s vanity.

Yes, there are economic and social realities that mean that wilderness areas are shrinking to make way for crops and other forms of land exploitation. Everybody understands that. But everybody should also understand that unless we embrace models of sustainable development, not only the elephants of Việt Nam will be doomed, our whole planet will be doomed.

The jungle and its animals were Việt Nam’s allies in the wars against invaders, colonisers and imperialists. They are now crying for help. But are we listening? VNS

.jpg)