World

World

The new special UN envoy to Syria began his first trip to Damascus on Tuesday, facing the daunting task of rekindling moribund peace talks and succeeding where his three predecessors failed.

|

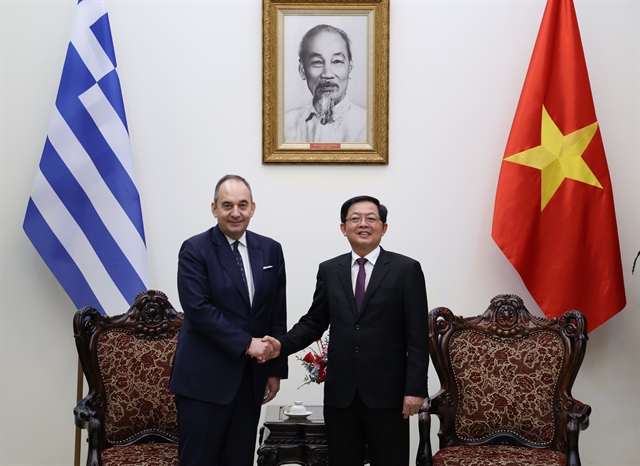

| The new UN envoy to Syria, Geir Pedersen, arrives in Damascus on his first visit since taking up post as the fourth head of the world body’s efforts to bring an end to the civil war which erupted in 2011. — AFP/VNA Photo |

DAMASCUS — The new special UN envoy to Syria began his first trip to Damascus on Tuesday, facing the daunting task of rekindling moribund peace talks and succeeding where his three predecessors failed.

Geir Pedersen’s visit comes at a time of heightened tension between the top foreign brokers of a conflict that has already killed more than 350,000 people and displaced millions.

Turkey and the United States are calling for the creation of a so-called "security zone" in northeastern Syria, a move the Kurdish militia controlling the area sees as a military occupation.

Pedersen, who replaces Staffan de Mistura, is the fourth negotiator to have been appointed UN special envoy to Syria since the civil war broke out in 2011.

The seasoned Norwegian diplomat, 63, held talks with senior Syrian officials, including Foreign Minister Walid Muallem.

Muallem expressed Syria’s "readiness to cooperate with him... in his mission to facilitate Syrian-Syrian dialogue with the objective of reaching a political solution to the Syrian crisis," a foreign ministry statement said.

Pedersen simply said upon arrival he was "looking forward to productive meetings here".

Officials in the government of President Bashar al-Assad had set the tone for the new envoy’s tenure shortly after his appointment was announced in October.

"Syria will cooperate with the new UN envoy Geir Pedersen provided he avoids the methods of his predecessor," Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal al-Meqdad had said.

Assad opponents have said the change in UN envoy would have little impact on the fate of the country as international will and consensus were lacking.

Low expectations?

Pedersen has not yet spoken publicly about his mission and it remains unclear what his approach will be.

De Mistura, who announced in October he was resigning for "personal reasons", ended his four-year tenure with an abortive push to form a committee tasked with drawing up a post-war constitution.

A track of peace talks in Geneva between the regime and the opposition is clinically dead, and observers argue Assad will see little need to revive it.

Three years into the conflict that erupted when the government repressed anti-regime demonstrations, Assad was clinging to barely a third of Syrian territory and his days at the helm looked numbered.

The Syrian president, who has been in power for more than 18 years, has now reclaimed much of the territory lost, largely thanks to military backing from Russia.

Non-jihadist opposition groups across Syria have little or no clout on the ground, and negligible bargaining power in negotiations with Damascus.

One of their main sponsors, Turkey, is pursuing its own agenda in Syria, notably a strategy aimed at undermining the Kurdish militia that controls a large swathe of the country’s northeast.

The People’s Protection Units (YPG) expanded its influence there when it became the main partner of the US-led coalition battling Islamic State jihadists in Syria.

But US President Donald Trump last month announced a complete troop pullout, which will leave the Kurds exposed to threats by Turkey, which considers the YPG a "terrorist" organisation.

‘Aggression’

Washington insists it wants Syria’s Kurds to be safe, but is also advocating for the creation of a buffer zone in northern Syria to protect Turkey.

What exactly such a "security zone" advocated by both the United States and Turkey would entail remains unclear, but the Syrian authorities are opposed to the idea.

Damascus denounced Ankara’s "language of occupation and aggression", after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Tuesday spoke of the buffer.

The "security zone", which Turkey says would run 30 kilometres deep into northern Syria, would cover much of the Kurdish heartland in the country.

The shock news of the US withdrawal, which the coalition says has already started, also raised fears that Iran would be allowed to further increase its own influence in Syria.

Iran has, with Russia, been the main backer of Assad, and its archfoe Israel is concerned that the Syrian conflict has allowed it to extend its military reach in the region.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned Tehran to "get out of there fast" or face increased attacks on its assets in Syria.

The battle however continues against the last IS holdout near the Iraqi border. — AFP