Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

|

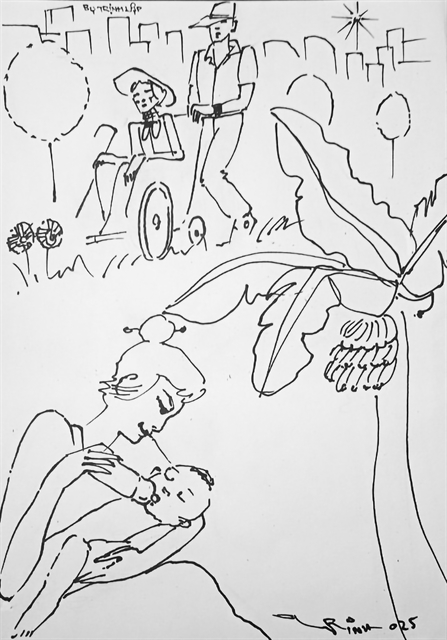

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

These days, it irritates me when some parents blame their children for being indifferent or neglectful towards them in old age. It's not easy to generalise how children should behave when their parents grow older, but I found a recent classroom activity in my teenage child’s school to be a helpful way to start that conversation.

In their microeconomics and law class, the students were asked: “What will you be doing 20 years from now?” While the subject name may sound grand, the course teaches basic, practical skills — like organising a sales booth at the school market fair, planning marketing strategies, investing in ingredients, cooking, styling, selling, and finally accounting for the day’s income. It helps students gain real-life skills, learn teamwork, calculate profit, and, of course, enjoy the leftovers.

As the students imagined their future selves — landing dream jobs, earning financial independence, exploring the world — their teacher dropped a reality check that caught everyone off guard: “Then you’ll start to take care of your ageing parents!”

Starting the conversation early

Is it too early to talk to high school students about such responsibilities? Is it too stressful to introduce the idea of caregiving when they're already juggling hormonal changes, academic pressure, entrance exams, and household chores — all while learning how to cook your favourite meal and clean up afterwards?

Adolescence is a fleeting phase, yet parents and educators often rush to fill it with useful life lessons, fearing that if these things aren’t discussed now, they’ll be harder to teach later. Once a mindset sets in, it can be difficult to shift.

Caring for ageing parents doesn’t have to be a heavy burden. It can start with simple gestures — asking about their day, their work, or how they’re feeling. It's about sharing joy, concern, and building open communication between generations. Setting expectations and acknowledging limitations from both sides can help meet each other’s needs.

In our busy lives, we often forget to ask: “Is this what they really want?” We might go out of our way to make our parents happy — only to find out they didn’t want what we offered at all.

And trying to figure out what our Vietnamese parents really want? That might be as tricky as finding a way up to the sky.

From a parent’s point of view, the last thing they want is to become a burden. Many would prefer not to trouble their children for anything if they can still manage on their own. “No, I don’t want that!” is a familiar refrain, even when the children genuinely want to do something kind.

In fact, many elderly Vietnamese parents go out of their way to help raise grandchildren, support their working children, and never ask for anything in return — a trait not unique to Việt Nam, but certainly strongly felt here.

One viral social media video summed it up perfectly: A Western mother asks her child to help move a heavy object and thanks them afterwards. A Vietnamese mother tries to move it herself, refuses help, finishes the job, then complains her child didn’t offer assistance. It's funny when it happens to someone else — but maddening when it happens to you and your own mother.

When words don’t come easy

It's already hard to know what a parent wants when they’re healthy. It’s even more difficult when they’re unwell or in pain.

If parents could speak frankly about what pleases them — and children could make an effort to understand — then perhaps we really could live happily ever after.

Sometimes, though, it’s okay to get angry. Frustration is natural. We admire those who channel that frustration into love and care — like the middle-aged man patiently caring for his mother with Alzheimer’s, even talking with her in the middle of the night when she wakes everyone up.

Another story tells of a son who tried to slow his mother's cognitive decline by pretending to hit his sister with a shoe — triggering the mother to come to her daughter's defence and whack the son with the other shoe. The whole scene ends with laughter and a kiss on the cheek.

There are many tricks and stories out there. Each family will have its own journey. But as long as your parents are still around, it’s never too early to start learning how to understand them — and that learning might well begin in the teenage years. VNS