Society

Society

|

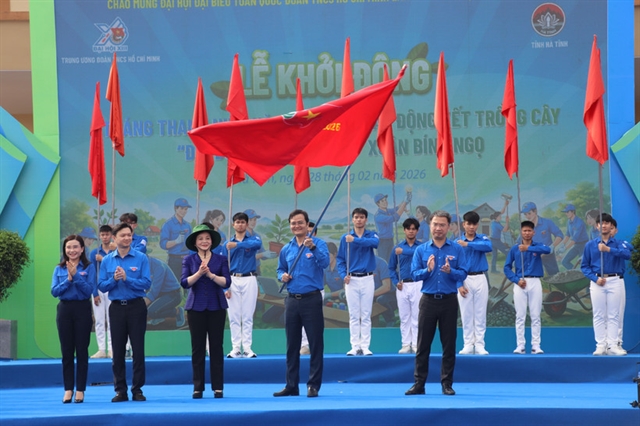

| The NovaWorld Phan Thiết project, developed by Novaland, where a disputed villa purchase led to a landmark court ruling on loan contracts and off-plan property sales. — Photo courtesy of the developer |

HCM CITY — A recent court ruling in HCM City that voided a VNĐ3.65 billion (US$145,000) loan contract between one of Việt Nam's largest private lenders and a local couple has triggered widespread debate in both the real estate and banking sectors.

Beyond the dispute itself, legal experts say the case highlights a deeper “grey zone” in Việt Nam’s property market: the widespread use of informal contracts in transactions involving homes that do not yet exist.

At the end of September, a local People’s Court dismissed VPBank’s lawsuit against borrower Trần Hồng Sơn and his wife, who defaulted on a loan to buy a villa at the NovaWorld Phan Thiết project.

The judges declared both the credit agreement and the villa purchase contract with Novareal JSC invalid, ruling that the broker was not legally authorised to collect deposits and the villa did not meet the legal threshold for sale.

VPBank and Novareal have both filed appeals, arguing that the lower court overstepped its jurisdiction and misapplied the law. But for many observers, the real story lies in what the case reveals about Việt Nam’s off-plan housing market.

Blurred lines of ‘paper houses’

Phạm Thanh Tuấn, a legal expert on property law, says the dispute underscores how buyers, banks, and developers are caught in a legal limbo when it comes to “buying houses on paper.”

“On the surface, it looks like a private dispute,” Tuấn said. “But in reality, it exposes a major grey area in transactions for houses still under construction, in which developers and brokers often sign vague contracts not recognised under housing or real estate laws.”

Under current regulations, developers can only sign sales contracts once foundations or basic infrastructure are completed and the Department of Construction certifies the project as “eligible for sale.”

But in practice, many projects launch earlier, using “reservation agreements,” “deposit contracts” or “memoranda of understanding” that rely only on the Civil Code.

These contracts skirt the stricter provisions of the Housing Law and Real Estate Business Law, creating what Tuấn calls “halfway documents” that give buyers little protection.

Despite the legal uncertainty, banks often extend credit based on these documents. Developers want cash flow and a chance to test market demand; buyers want to secure units at attractive prices; banks see an opportunity to expand lending.

“It makes sense economically,” Tuấn noted. “But legally it’s precarious. When disputes arise, courts struggle to balance fairness and the letter of the law. That’s what we saw in the VPBank case.”

Legal loophole

Current law allows developers to take deposits of up to 5 per cent of a unit’s value once a project is eligible for sale. But as Tuấn points out, that rule is toothless.

“If a project is already eligible, no developer will stop at 5 per cent. They will sign sales contracts and immediately collect 30 per cent,” he said. “So in reality, the 5 per cent rule does nothing to regulate the pre-sale phase.”

Tuấn suggests lawmakers should use the upcoming revision of the Real Estate Business Law to create a clear, transparent framework for pre-sales. This could allow developers to take early payments capped at a modest percentage, for example 10 per cent, but only once minimum conditions are met, such as the land handover and approved design plans.

Crucially, the funds should be held by a third party, preferably a bank, and only released once the project is officially cleared for sale.

“This would benefit everyone,” Tuấn argued. “Buyers reduce their risk, serious developers get transparent financing, and regulators can supervise more effectively. It would eliminate the thousands of ‘grey contracts’ now flooding the market.”

Lessons from the case

The VPBank-Novareal dispute is now on appeal, and its final outcome may set a precedent for similar cases. But regardless of the verdict, experts say the case has already spotlighted the urgent need for stronger legal foundations.

“People need solid contracts to place their trust,” Tuấn said. “Developers need lawful ways to raise capital. But right now, between ambition and reality, there’s a legal grey zone where everyone is left to fend for themselves.”

In the end, Tuấn added, a healthy real estate market is not just about skyscrapers rising from the ground. “It starts with a solid legal footing. Trust in the law is the true foundation of every home.” — VNS

.jpg)