Life & Style

Life & Style

Modern mammals, including humans, owe their keen sense of hearing to three tiny bones in the middle ear that were absent in their reptile ancestors, but the point at which this transformation occurred has remained unclear.

|

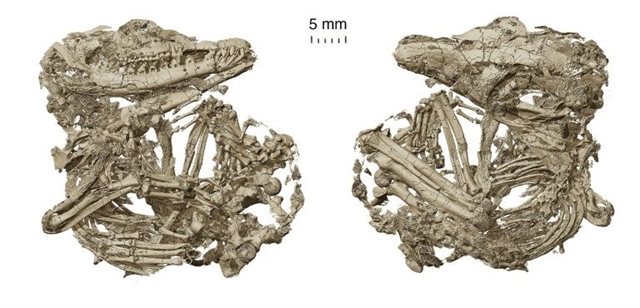

| Using high resolution CT scans and other imaging techniques, the Chinese-led team were able to describe the well-preserved specimens in detail, including the structures of their auditory bones and cartilage. — AFP/VNA Photo |

WASHINGTON — Modern mammals, including humans, owe their keen sense of hearing to three tiny bones in the middle ear that were absent in their reptile ancestors, but the point at which this transformation occurred has remained unclear.

Scientists have now identified the transitional stages in the remains of a newly discovered species that lived 125 million years ago in what is now northeastern China: effectively a missing link in the evolutionary chain.

Their findings were published in the journal Science on Thursday and welcomed as a landmark moment in the field of paleontology by peers.

"It's a fantastic set of evidence," Guillermo Rougier, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Louisville who was not involved in the research said, adding that the specimens the team had studied were "breathtaking."

Senior author Jin Meng of the American Museum of Natural History in New York explained that the study was based on the remains of six individual animals, proto-mammals from the Early Cretaceous they have named "Origolestes lii," who lived alongside dinosaurs and were rodent-like in size and appearance.

Reptiles use their jaws to both chew and to transmit external sound via vibrations to their brains, unlike the more delicate and complex hearing system in mammals involving the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones responsible for everything from musical appreciation in humans to echolocation in dolphins.

Scientists have hypothesised that the so-called "decoupling" of the hearing and chewing system removed the physical constraints the two processes placed on each other, allowing mammals to both diversify their diet and improve their hearing.

Using high resolution CT scans and other imaging techniques, the Chinese-led team were able to describe the well-preserved specimens in detail, including the structures of their auditory bones and cartilage, which lacked the bone-on-bone contact of earlier species.

"Now we have provided the fossil evidence in the evolutionary time which echoes the hypothesis," said Meng.

Rougier meanwhile said the discovered fossils were a treasure trove for researchers. "It's an embarrassment of riches, truly."

He added it was a "big step in our ideas and concepts and the material basis on which we can discuss very intricate evolutionary processes."

But the study now posed a new question, he said: whether this process happened in all mammals or a small subset of mammals.

"Did it happen once, did it happen in different groups? We're moving the boundary of what we can ask."

Meng said he and colleagues were now examining other parts of the Origolestes fossils including the brain cavity, the topic of future papers that delve further into the early evolution of mammals. AFP