One does not always need to use hard materials to build walls to keep flood waters out of fields and villages.

|

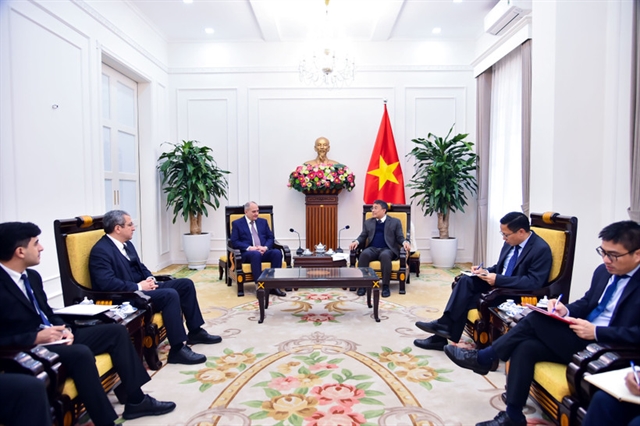

| A soil dyke section in Triêm Tây Village of Quảng Nam Province is covered by native grass to prevent erosion during the flood season. — Photo courtesy of An Nhiên Farm |

One does not always need to use hard materials to build walls to keep flood waters out of fields and villages.

An architect called Ngô Anh Đào has made a soft wall to do the job.

She and her partner, Vũ Thị Mỹ Hạnh used environmentally-friendly material, such as bamboo, sand and clumps of reeds.

They also grew plants on their wall – and it works.

These days it is more difficult to tell when rivers will flood so it is important to have a good wall, or dyke as such walls are called.

By Công Thành

Architect Ngô Anh Đào designed her first “green” river dyke by looking at the natural structures that plants use to survive environmental changes. The dyke provides what she calls a “soft” riverbank protection solution in Triêm Tây Village.

Đào, who studied urban planning and landscape design at the University of Montreal, Canada, used multiple layers of indigenous flora and environmentally friendly material to build the dyke.

She and her partner, Vũ Thị Mỹ Hạnh, director of An Nhiên Farm, constructed it as part of a series of projects to provide social education and skills training for farmers. The farm is an agriculture laboratory of sorts, using natural methods and tools that can be replicated on a larger scale. The dyke is their effort to solve an existential threat facing Vietnamese farmers: ever-worsening floods.

Starting in 2016, they grew local plants to test how well they resisted flood waters, contrasting their “soft” organic design with a “hard” system of man-made walls.

“[The system] means that powerful flood water could be eased by the soft and flexible strength of a deep complex of roots and surrounding soil. It’s based on the natural co-existence of flora and ,” Đào said.

Organic materials used to build the dyke include local grass, bamboo, cloth tubes of sand and reed clumps to anchor the soil that serves as the dyke’s foundation.

Mangrove (sonneratia caseolaris) was chosen to reduce water pressure breaker on the outer layer of the dyke.

“The mangrove can grow quickly, and its roots create a safe shelter for marine creatures, as well as reduce water pressure by allowing free space for water to come in and out easily,” she explained.

“It reduces the breaking force of high tide. Only water comes out through mangrove roots, but alluvial soil are retained. This means that the dyke is naturally reinforced by sand and mud every time the tide comes in.”

First loss

Đào and Hạnh suffered their first setback during their first pilot project, when they planted the mangrove outside the dyke without an anchor. The 2017 flood, which soaked Triêm Tây Village over a period of nine days—the longest flood in the village history—washed away the eight-month-old unanchored mangrove.

“We neglected to build a water shield on the outer layer. Mangrove needs at least two years to take strong root in the soil, but the unforeseen flood lashed the young mangrove,” Hạnh recalled.

They learned from that mistake.

“The next time, we built a bamboo wall on the front layer to protect the mangrove in the initial period, while a strong local grass species was grown behind the mangrove layer to provide another layer to defend the river bank from erosion,” Hạnh said.

The Hanoian said the structure of the dyke, modeled on a diverse forest, which was grown from casuarinas, bamboo and native bushes, has given the farm a strong defence against disaster.

She said a sapling garden of flood-resistant plants was built on the farm to create supplies that can be used to construct a larger green dyke in the future.

Villager Vũ Đức Sinh, a member of the village’s community-based eco-tourism co-operative, said he has witnessed serious erosion in the village for decades. Villagers did not know how to stop the floods from washing away the farmlands.

“As a rule, a heavy flood occurs every five years, but unpredictable water flow from the discharge of hydro-power plants and forest destruction in the riverheads caused the erosion to worsen,” Sinh said.

“The increasing erosions had jolted our lives, with farm lands narrowing each year due to larger and longer floods in recent decades,” Sinh said.

He said at least 50ha of farm land had been washed away by floods over two decades.

Technique

Concrete walls had been built to strengthen the village’s riverbanks, but erosion dug deeply into the soil at the bottom of the wall, severely damaging the structure.

Đào said concrete structure cannot defend a riverbank against long-term attacks of water.

That is why Đào chose organic materials like bamboo, logs and sandbags to anchor the green dyke.

“We divided the work into different sections, and each section connects to the other with plant layers. It’s the way a forest grows, and we just learnt how to build it from nature,” Đào said.

She said the green dyke development also involved the community, as they acknowledged the importance of riverbank protection.

A collection of 200 flora species have been raised at An Nhiên Farm’s sapling garden to create sustainable supply for the green dykes.

Nguyễn Thị Phúc Hòa, an expert in disaster and risk management, said An Nhiên Farm’s green structure wall was a good example of a long term resilience solution to climate change.

She said the nature-based dyke will be an option for climate change-affected coastal areas in the future, as people learn to live with what were once regarded as disasters.

“Mangrove can live in brackish water and it can protect riverbanks from erosion during heavy floods and high tide. The forest-built dyke is based on the natural rule that flora can survive disaster,” Hòa said.

Hòa said Quảng Nam Province had been boosting the development of mangrove forests and seeking sustainable ways of protecting the long coast line and wetland areas from forecast bigger disasters in the future.

‘Green’ development

The administration of ancient Hội An City has been applying the green dyke solution for the worst eroded sections of the riverbank.

Nguyễn Thế Hùng, vice chairman of Hội An City’s people’s committee, said the An Nhiên Farm green dyke was seen as an effective and sustainable protection measure for the city’s riverbanks.

Hùng said the city, in co-operation with the An Nhiên Farm, began building a 700m green dyke section in connection with the farm’s already-built 250m soft dyke.

“We learned from the experience of An Nhiên’s unprotected mangrove layer destroyed during the 2017 flood, so we set rock walls on the outside to protect the newly grown mangrove from damage. Mangrove needs to grow strong as it can protect the inner layers of the grass, bushes and soil dyke,” Hùng said.

“The city plans to set up more green dyke sections to protect the most vulnerable eroded areas in Cẩm Kim and Cẩm Nam villages along the Thu Bồn River,” he said, adding that the green dyke costs only a third of a concrete dyke.

Hùng said the green dyke would help reduce the speed of high tide waves on the riverbanks, while roots retain alluvia to reinforce the base of the soil dyke.

He said Hội An City had been seeking green and sustainable solutions to preserve the city and its landscape as an UNESCO-recognised world heritage site.

"Hội An’s old quarter and its river system is closely linked with the world biosphere of the Chàm Islands, and sustainable preservation will be top priority of the city," he added.

Mastermind of the green dyke Đào said she hoped the solution would help Triêm Tây Village’s dyke stand strong through future floods, and prevent erosion in the future.

“I keep growing more flood resistant plants for the long development of green riverbank protection in the most vulnerable sites in coastal areas in central Việt Nam. Please, behave tenderly towards nature, and we should learn to live with disaster softly,” she said. — VNS

GLOSSARY

Architect Ngô Anh Đào designed her first “green” river dyke by looking at the natural structures that plants use to survive environmental changes.

A dyke is a wall made of earth to stop water coming on to low-lying lands.

Đào, who studied urban planning and landscape design at the University of Montreal, Canada, used multiple layers of indigenous flora and environmentally friendly material to build the dyke.

Urban planning is the planning of towns and cities.

Multiple means many.

Indigenous flora means plants from the country in which they are growing and not plant types that have been brought in from anywhere else.

If something is environmentally-friendly it does not harm the environment.

She and her partner, Vũ Thị Mỹ Hạnh, director of An Nhiên Farm, constructed it as part of a series of projects to provide social education and skills training for farmers.

Constructed means built.

A series of projects means a string of projects that all have something to do with one another.

The farm is an agriculture laboratory of sorts, using natural methods and tools that can be replicated on a larger scale.

A laboratory is a place where experiments are carried out.

Replicated means copied.

The dyke is their effort to solve an existential threat facing Vietnamese farmers: ever-worsening floods.

If something is existential, it exists.

Starting in 2016, they grew local plants to test how well they resisted flood waters, contrasting their “soft” organic design with a “hard” system of man-made walls.

Resisted means “fought against”.

Contrasting means “being different to”

Organic, in this case, means “made from living things”.

“[The system] means that powerful flood water could be eased by the soft and flexible strength of a deep complex of roots and surrounding soil.

If something is flexible it can be changed and moved around.

Organic materials used to build the dyke include local grass, bamboo, cloth tubes of sand and reed clumps to anchor the soil that serves as the dyke’s foundation.

To anchor the soil means to hold it down.

“The mangrove can grow quickly, and its roots create a safe shelter for marine creatures, as well as reduce water pressure by allowing free space for water to come in and out easily,” she explained.

Marine means to do with the oceans.

“It reduces the breaking force of high tide.

High tide is the tide at the time of day when the sea level gets higher.

Only water comes out through mangrove roots, but alluvial soil are retained.

Alluvial means to do the clay, soil and other debris brought down by a river.

Retained means kept.

This means that the dyke is naturally reinforced by sand and mud every time the tide comes in.

Reinforced means “made stronger”.

Đào and Hạnh suffered their first setback during their first pilot project, when they planted the mangrove outside the dyke without an anchor.

A setback is a disadvantage.

A pilot project is a test to see if something will work by trying it out first on a smaller scale.

“We neglected to build a water shield on the outer layer.

Neglected means forgotten in a careless way.

Mangrove needs at least two years to take strong root in the soil, but the unforeseen flood lashed the young mangrove,” Hạnh recalled.

Unforeseen means not picked up as something that was going to happen.

“The next time, we built a bamboo wall on the front layer to protect the mangrove in the initial period, while a strong local grass species was grown behind the mangrove layer to provide another layer to defend the river bank from erosion,” Hạnh said.

Initial means first.

A species of grass is a type of grass.

Erosion is weathering that changes the shape of the land.

The Hanoian said the structure of the dyke, modeled on a diverse forest, which was grown from casuarinas, bamboo and native bushes, has given the farm a strong defence against disaster.

A Hanoian is someone from the capital city.

If a forest is diverse it had many different types of plants.

She said a sapling garden of flood-resistant plants was built on the farm to create supplies that can be used to construct a larger green dyke in the future.

A sapling is a little tree.

Villager Vũ Đức Sinh, a member of the village’s community-based eco-tourism co-operative, said he has witnessed serious erosion in the village for decades.

Eco-tourism is tourism with an environmental theme.

“As a rule, a heavy flood occurs every five years, but unpredictable water flow from the discharge of hydro-power plants and forest destruction in the riverheads caused the erosion to worsen,” Sinh said.

If water flow is unpredictable, it is difficult to tell what it will be from one day to the next.

The discharge of hydro-power is the fast flow water that comes out of the hydro-electric plant as a result of the plant’s activities.

Hydro-power is electricity made from capturing the energy of fast moving water.

Destruction happens when something is broken and ruined.

“The increasing erosions had jolted our lives, with farm lands narrowing each year due to larger and longer floods in recent decades,” Sinh said.

Jolted means affected in a very sudden way.

A decade is a period of ten years.

She said the green dyke development also involved the community, as they acknowledged the importance of riverbank protection.

To acknowledge something means to accept it.

A collection of 200 flora species have been raised at An Nhiên Farm’s sapling garden to create sustainable supply for the green dykes.

If something is sustainable it can keep on going.

Nguyễn Thị Phúc Hòa, an expert in disaster and risk management, said An Nhiên Farm’s green structure wall was a good example of a long term resilience solution to climate change.

Resilience means toughness.

“Mangrove can live in brackish water and it can protect riverbanks from erosion during heavy floods and high tide.

Brackish water is water that is a little bit salty.

“The city plans to set up more green dyke sections to protect the most vulnerable eroded areas in Cẩm Kim and Cẩm Nam villages along the Thu Bồn River,” he said, adding that the green dyke costs only a third of a concrete dyke.

Something that is vulnerable can easily be harmed.

Hùng said the green dyke would help reduce the speed of high tide waves on the riverbanks, while roots retain alluvia to reinforce the base of the soil dyke.

To retain alluvia means to keep the silt, soil and other things that are washed down a river and land up in the river bed.

He said Hội An City had been seeking green and sustainable solutions to preserve the city and its landscape as an UNESCO-recognised world heritage site.

A world heritage site is a special place that is so special it is not only important to the country in which it is located but to all countries. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or Unesco, decides which places should be world heritage sites.

"Hội An’s old quarter and its river system is closely linked with the world biosphere of the Chàm Islands, and sustainable preservation will be top priority of the city," he added.

A biosphere is a piece of the earth occupied by living things, such as plants and animals.

A priority is something that must be done before other things that may need to be done.

Please, behave tenderly towards nature, and we should learn to live with disaster softly,” she said.

Tenderly means gently.

WORKSHEET

State whether the following sentences are true, or false:

ANSWERS: 1. True; 2. True; 3. False; 4. False; 5. True.

Brandinfo

Brandinfo