Economy

Economy

The fifth plenary meeting of the 12th Communist Party of Việt Nam Central Committee in May issued an important resolution which acknowledges greater contribution of the private economy to the country’s socio-economic growth and asserts the role of the private economy as “an important driving force of the socialist-oriented market economy”.

|

| Cà Mau Fertiliser Plant with annual capacity of 800,000 tonnes located at Cà Mau Gas-Electricity-Fertiliser industrial cluster in Khánh An commune of the southern province of Cà Mau’s U Minh district. — VNA/VNS Photo Huy Hùng |

It asserts the role of the private economy as “an important driving force of the socialist-oriented market economy”.

After 30 years of Đổi mới (renovation process launched in 1986), one of the most remarkable achievements of Việt Nam’s economic reforms is the emergence of a dynamic private sector.

However, this has not been a smooth process. It has been complicated and rough. The complications are reflected in how the terms used have evolved, from the so-called “multi-sectoral commodity economy” and “market mechanism under State management” to “socialist-oriented market economy.”

Before Đổi mới, Việt Nam was essentially a centrally-planned economy in which the Government administered supply of physical inputs and outputs and the economy recognized only State and collective ownership of means of production. There was basically no business autonomy.

For the private sector, the year 1986 marked the beginning of an irreversible change in ideology, following which the Government pushed forward a mixed market economy model with a multiple ownership structure.

In the early 1990s, Việt Nam adopted a radical and comprehensive reform package aimed at stabilizing and opening the economy, and enhancing freedom of choice for economic units and competition. For the first time, the Government demonstrated its support for development of the domestic private sector.

The year 2000 was the next important turning-point for private sector development. The introduction of the Enterprise Law significantly reduced administrative burdens for business registration, resulting in a dramatic increase in the number of registered private businesses.

Since then, the private sector has been growing strongly, accounting for 39-40 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). It is noteworthy that the private sector also became a major source of employment, absorbing about 85 per cent of the 1.3-1.4 million new labour market entrants each year.

We can now see the image of a dynamic and prominent private sector with a large number of entrepreneurs covering three to four generations, struggling to succeed, as well as a powerful start-up movement. In 2016, the country saw a record number of newly-established enterprises, over 110,000, bringing the total number of private enterprises to 610,000.

So the main factors in the development of the private sector are State acknowledgment of its role, private property ownership and business autonomy, as well as the Government’s support policies.

The new Resolution endorsing it as a prerequisite for national growth reaffirms the Government’s commitment to providing a solid momentum for the private sector to grow in a sustainable manner.

Strong numbers, weak growth

Việt Nam currently has around 610,000 private firms, but a majority of the registered enterprises are micro-sized with 70 per cent of them employing less than 10 workers and having a registered capital of below VNĐ5 billion (US$220,300).

The number of big companies has been growing, but they are yet to demonstrate their leadership in innovation and driving growth.

Another concern is the downsizing trend among private enterprises, which has prevented productivity gains through economies of scale, specialization and innovation. Many small household businesses have refused to register as formal enterprises, citing bureaucratic and regulatory problems, concerns over the security of property rights and high transaction costs.

Private companies have a prominent position in several industrial clusters, like textiles and garments, footwear and others. But it is notable that the overall structure of the private sector is not balanced, with over 80 per cent concentrating on trade and services sectors with low productivity and low value-added products and services. The number of private firms in manufacturing and processing is small.

It can also be seen that private enterprises have been facing many difficulties in doing business, with the rate of loss-making and bankrupt companies at a high average of 45 per cent in the 2007-2015 period.

The Việt Nam 2035 Report shows that the productivity and competitiveness of Vietnamese private sector are decreasing. Vietnamese firms are engaged in the global/regional production network but with weak positions in the global/regional value chains.

All of these facts suggest that there has been a lot of obstacles for private businesses to grow and eventually make it to the top.

The impediments

The low quality growth of the private sector can be attributed to many factors, including weak property rights, uneven playing field, distortions in factor markets, difficult access to production factors, as well as high transaction costs.

Legally, the greatest weakness is probably the framework responsible for ensuring private property rights and securing free and fair competition. Weak enforcement of land-use and intellectual property rights has impeded the emergence of large and competitive private firms.

The fact that the State-owned enterprises dominate many industries and enjoy preferential treatment through cozy relationships with government officials is also reducing business opportunities for private companies.

The unfair business environment is also shown in inadequate access to land, capital, information, infrastructure and labour for the private sector, raising transaction cost, which is arguably very high, given the unofficial costs caused by red-tape.

Meanwhile, the competition authority has not done its job well due to rather weak power and independence.

Matters are not helped by the weak capacity of private firms in terms of legal and market savvy, development vision and networking, not to mention weak corporate governance and culture.

The right path

Economists and entrepreneurs have discussed and proposed several initiatives and measures to the Government to spur sustainable growth of the private economy along with equitisation and reform of State-owned enterprises. But this is a long process which needs both consistent effort from private firms and consistent support from the Government.

Stronger institutional reforms are needed to move forward, relaxing bureaucratic scrutiny on doing business, while securing fair competition by improving access to land, capital, information and other production factors for private firms.

In the context of Việt Nam integrating deeper into the global market, the establishment of strong industrial clusters (IC) so that the private sector has a site to do business will help boost productivity of Vietnamese firms while promoting exports and encouraging innovation.

The Government should identify already existing clusters and potential “seeds” and avoid institutional complexity. It should consider the development of supporting industries and local SMEs an important component of IC policy.

For promoting innovation, the Government has issued policies and established funds to support research and development (R&D), but the efficiency and spillover effect have been limited.

Looking at the experience from South Korea and Japan, where SMEs have a leading position in R&D activity, the Government can offer direct and indirect financial support, including tax relief for hi-tech firms and providing funds to firms with good track records.

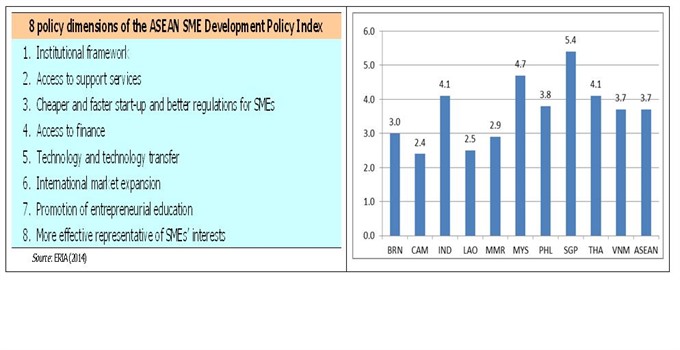

ASEAN and Việt Nam have a strategy to improve the business environment for SMEs to become more competitive, innovative and dynamic. This is based on eight policy dimensions. Việt Nam has an average position on SME Policy Index compared to other ASEAN members, which means there is a lot of room for development.

We have to think of private business as ours and take ownership accordingly. It is vital for our economy. Having a dynamic and competitive private sector is a solid guarantee for Việt Nam’s development and prosperity. Its success will depend on how we bring into reality the right institutions and support policies.

* Võ Trí Thành is a senior economist at the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) and a member of the National Financial and Monetary Policy Advisory Council. A doctorate holder in economics from the Australian National University, Thành mainly undertakes research and provides consultation on issues related to macroeconomic policies, trade liberalisation and international economic integration. Other areas of interest include institutional reforms and financial systems. He authors Việt Nam News’s new column, “Analyst’s Pick,” which will run on the first Tuesday of every month.

|

| Võ Trí Thành |

|

| The ranking of Asean SMEs development policy index. — Photo economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) |