Features

Features

Excerpts from memoir Ship With Paper Sails, Story of a Hanoi Newsman* by Nguyễn Khuyến, former Viet Nam News Editor-in-Chief

|

| Nguyễn Khuyến, former Viet Nam News Editor-in-Chief |

Excerpts from memoir Ship With Paper Sails, Story of a Hanoi Newsman* by Nguyễn Khuyến, former Viet Nam News Editor-in-Chief

I cannot claim to have been more exposed to war hazards than were other average residents in Hà Nội in those years of war, and certainly no more than members of the Militia, the Fire Brigade and the Red Cross. In fact, care was even taken to protect me and some other "assets" of the Foreign Desk from unnecessary risks. Early in 1965, Trần Văn Chương and I were secreted to a sort of "safe base," a cave among a cluster of massive limestone outcrops west of the city, where the agency had set up a reserve transmitter. For a week, we were drilled in emergency measures in the utter stillness of the natural bunker.

This protective cocoon notwithstanding, I remained in Hà Nội throughout the American air war, to be close to "where the action is". In the absence of my wife and children, who were evacuated to the countryside again and again, I would stay at the office, sleeping on my desk, cooking my own meals.

To escape desk duties, I would jump at the slightest opportunity to do the beat: to cover fresh scenes of bombing. This activity was virtually safe. By the time you got there, the All Clear had been sounded. All you had to do was collect as much information as you could about the casualties, damage done and, if any, the number of aircraft downed or hit and of pilots captured or killed. You also took a few photos. Then, it was "mission accomplished", provided nothing happened on your way back.

I had many "escapes" this way during 1972, when Hà Nội and Hải Phòng were targeted by massive strikes. One damaged the office of the International Commission for Supervision and Control at 7 Lý Thường Kiệt, next door to the Vietnam News Agency at 5. I wonder now if the VNA had been the real target. This commission, with India, Poland and Canada for members, was set up under the 1954 Geneva Agreements on Indochina to help strengthen and consolidate the armistice. One Indian was killed and the front of the British Government’s representative’s residence at 16 across the street was splattered with bomb pellets.

On Trần Hưng Đạo Street, which runs parallel to Lý Thường Kiệt, the French embassy was hit, as was the Indian embassy.

One night in 1972, the home of my wife’s uncle in a southern suburb got a direct hit. The uncle, his wife and seven of their children were blown to smithereens. Rescuers had to sift through mud for whatever remained of the victims and were not sure if they could ever succeed.

Their graves now occupy a whole row at one of the largest cemeteries in Hà Nội.

The home of my father-in-law miraculously stood after a B-52 raid on An Dương, a densely populated workingclass area. Dozens of inhabitants were killed or wounded.

By sheer chance, I had just moved my wife and my three-year-old daughter from there to a garret at the top of the main VNA building so we could have ready access to a spacious bunker built beneath a newly completed four-storey wing. Some neighbours later turned a cold shoulder on me, as if I had received a tip-off but had kept it from them.

Besides An Dương, I saw some other scenes of carnage and destruction, but none was more shocking than the view of Khâm Thiên Street in the aftermath of the notorious strike at 10 pm on Boxing Day of 1972 that killed some 300 inhabitants. Vast swaths of the street had been levelled, and the place was littered with charred, twisted furniture and shredded personal belongings. The dead had been removed by the time I arrived before dawn, but hair, bloody strips of clothings and human flesh were still stuck on power and telephone lines.

I picked my way down the street for about a hundred metres and I made a sharp turn. I was no quitter, but there was a limit to what my heart could stand. Unbeknown to me, Joan Baez was to come to Khâm Thiên some time later in the day. There, the sight of an old woman in tears looking for her son moved the iconic American folk singer, song-writer, musician and activist to write Where are you now, my son?

I am a resident of Khâm Thiên now, having moved house to an alley just behind that street in 2000. Directly across the street is an open area where two contiguous houses once stood. In the middle is a monument. A woman holds a child in her arms. Memorial services have been held there annually, drawing large numbers of residents among them relatives of the victims. Passers-by who remember the tragic event stop for a moment of silence.

My luck held during the many trips on the frequently attacked railway between Hà Nội and Hài Phòng one hundred kilometres to the south-east. It took a whole night to cover the distance whereas, in normal times, two and a half hours suffice.

All the three bridges on that stretch were beyond repair after repeated strikes. At each crossing, passengers would have to disembark and, bending under their luggage, would trudge downstream, knee-high in mud, across rice fields dotted with bomb craters, to where a half-submerged pontoon bridge had been rigged up in a rush by army engineers to take them to the opposite bank. Then they would drag their feet upstream and, with great relief, board a freshly assembled train puffing impatiently on the tracks.

All the while, an airborne flare might pop overhead, illuminating the night sky with its sickly white glare. People would throw themselves flat on the ground for a tense moment until the flare died down.

Hải Phòng had been relatively quiet until April 1972, when US President Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker to destroy "military targets anywhere" including Hà Nội and Hải Phòng.

This led to the mining of the Hải Phòng Harbour in May and peaked with Operation Linebacker II launched on December 18, which was the last desperate attempt of the Nixon’s administration to "break the will" of the Vietnamese people.

Operation Linebacker II was the largest heavy bomber strike by US Air Force since the end of World War II, conducted mainly by B-52 Stratofortresses rather than by tactical fighter aircraft. Altogether, B-52s and Navy and Air Force fighter-bombers made a total of 729 attacks, dropping some 15,000 tons of explosive on North Việt Nam, mainly on its two largest cities.

In Hà Nội, other than the devastation of Khâm Thiên Street on Boxing Day, the Bach Mai Hospital just two kilometres to the south was hit by a string of bombs on December 22, the fifth day of this massive bombing drive. One wing of the hospital was levelled, and 28 doctors, nurses and pharmacists were killed.

The attacks on Bạch Mai and Khâm Thiên were probably the closest shaves I ever had. Both times I was at home, in a fourth-floor room in an apartment building at Kim Liên, a crowded residential area. Kim Liên is roughly midway between Bạch Mai to the south and Khâm Thiên to the north, and the distance between them is two kilometres as the crow flies. A string of bombs released from a high-flying bomber one-tenth of a second too soon or too late would have been a different story.

My old home at 288 Phan Bội Châu Street in Hải Phòng was not a different case. It was razed to the ground at the peak of Operation Linebacker II.

By sheer chance my family was unscathed. My mother had been evacuated to the suburbs together with my sisters and their children soon after the start of the harbour blockade in May.

In Hà Nội, commuting between work and home was a rather risky affair. In the first two years of my marriage, I stayed with my wife’s family in a northern suburb. Like most residents, I travelled mainly by tram, a very efficient means of mass transport in those days.

The ancient trams — their bells clanging and their wheels screeching on the steel rails, sending forth sparks from time to time — trundled on day in and day out. They were not always on time, what with the difficult passage through the winding, narrow, pedestrian-thronged streets and the frequent delays caused by farmers jostling up and down with their loads of fresh produce for the city’s many markets. But they were cheap effective and had been a fixture of Hà Nội life for as long as anyone could remember.

Regrettably, those beloved trams vanished one after another in the early 1980’s. In an ill-conceived decision, the municipal authority replaced them with what looked like a cross between a tram and a bus - vehicles running on pneumatic wheels and powered by the same overhead wires previously used for trams. As it was, the substitutes, nicknamed "oversized hearses" for their lumbering gait, were soon abandoned because of their impracticality.

Going by tram, then, was the most convenient way to go to work and return to my wife and my newborn baby at An Dương. But I’d then have to run the risk of being caught in the middle of an alert somewhere between the Long Biên Bridge across the Red River — vital for rail and road transport between Hà Nội and Hải Phòng — and the Yên Phụ Power Plant, both repeatedly targeted and heavily damaged but never completely put out of operation.

My luck held out throughout a month-long journey to the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) between North and South Việt Nam at the 17th parallel in May-June 1966. Our group — visiting Bulgarian journalist Russi Bojanov; Việt Long, a local VNA bureaux chief; and I — covered the distance of over five hundred kilometres one way in two weeks (the actual mileage was much longer because of the many detours taken to avoid potential bombing targets).

We travelled by night only, hitting the road at dusk, stopping at the crack of dawn. Night driving might as well be called blind driving. In lieu of headlights, a 40 watt bulb attached to the undercarriage was all you could depend on for light. Driving was like crawling. Still, groping in the dark and moving was more enviable than lying flat on your stomach in the weird glare of those hateful airborne flares and waiting for bombs to fall. Moving gave you a sense of being alive.

Yet, despite the anguish of being spotted by the aircraft above, I more than once pushed bulky Bojanov down the only shelter available despite his vehement protest, and remained flat on the ground above close to him.

FULLY ALERT

Quảng Bình

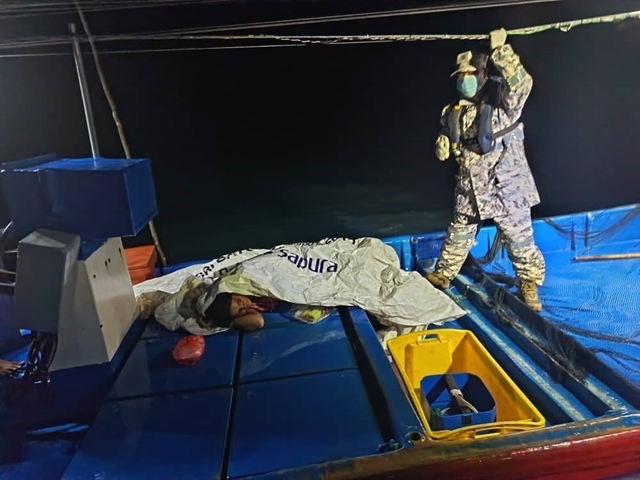

Colleague Việt Long and I (left) on the Nhật Lệ River, Quảng Binh Province, watchful for signs of American warplanes. About 100 km further south is our final destination, the demarcation line dividing Việt Nam at the 17th parallel.

Back in Hà Nội, the first time I came in direct contact with an American pilot was one cold night late in October 1972. As we were huddling in the huge underground bunker at the VNA one night while an air-raid alert was on, VNA Director-General Đào Tùng picked up one of the phones arrayed beside him. He listened for a while and beckoned me. "It’s the Hà Nội Garrison," he said. "They need an interpreter. A car is waiting for you."

I did not know what was expected of me. An excited crowd had already formed in the vast courtyard when I arrived. Shortly after, a white van pulled up and a big American was led down from it. He had been brought directly from the site of a newly downed B-52 bomber. A Vietnamese officer, probably the man in charge, called my name and, after a hurried handshake, asked me to act as his interpreter.

I don’t remember what the officer asked and what the American answered during that brief interrogation. I suppose it was just the usual — the captive’s name, unit, serial number, job, kind of aircraft, home base, and so on. I can’t recall the name of the American either for I didn’t take notes. What is clear in my mind’s eyes now is the image of the captive shivering and mumbling on a night of a Hà Nội winter.

The sight of that utterly broken man caused a stir in my heart. But someone at my back got impatient. "Why don’t you give him a slap to make him talk louder?" he hissed into my ear.

I just pretended deafness and went on with the interpretation. Memories of that unpleasant encounter were still pestering me when, early on January 27, 1973, the Foreign Desk literally exploded with joy: An agreement on ending the war and restoring peace in Việt Nam had been signed in Paris by the Democratic Republic of Việt Nam and the National Front for the Liberation of South Việt Nam on the one hand, and by the United States and the Republic of Việt Nam on the other.

At long last, the tough negotiations that dragged on and on from 1968 had come to an end. Gone were our long, bleary-eyed night shifts.

The great news also filled me with expectation — reunion with my wife and children, who I knew were on their way back from the countryside, where they had gone long before the start of the last waves of American bombing.

I was restless throughout the day. At night, while preparing for the last newscast, I kept glancing from the VNA third-floor window down the road below, straining my ears for any noise of heavy vehicles.

I took a moment to see a reflection of myself in a cracked window glass pane. Surely I was now just 50 or 51 kilograms, and gaunt before my time. It seemed just yesterday I had appeared heavier and stronger, and my smiles would have been more or less part of my known persona, for I was not naturally a negative person, but someone always trying to see the positives in life.

That was the feeling I wished to have once more about myself and life, after this recent wave of destruction. I saw the bright headlights long before I saw the vehicles or heard the friendly low-geared revving of their powerful motors. So vehicles had dispensed with the glow-worm lights under the radiators which were mandatory for night driving under bombing.

I sprinted down the stairs, my feet hardly touching the treads, and joined other staffers gathered on both sides of the street to welcome their loved ones.

We craned our necks towards the far end of the street where it intersected another street at a sharp angle. Then the first lorry — a Molotoba — rounded the corner, followed by another and still another.

We cheered as the dust-caked vehicles pulled up along the kerb, headlights full on, horns blaring madly. From inside their tarpaulin covers came excited chatters. No familiar faces in the first vehicle! Then from the second, or was it the third? I thought I heard a distinctly familiar voice calling my name. It was my wife. I shouted back. Out of the flap at the rear of the vehicle, I received from her, first the youngest daughter, aged 4, then the older, aged 8. My mother, who had been with us for the past month, clambered down all by herself. My wife was the last to join me on the road, weighed down by a bag of clothes. They had changed since I last saw them a month before, much thinner. Clutching them to my breast I could feel how frail they were.

We went home in our own convoys — two bicycles — I and my daughters on one; my wife, my mother and our belongings on the other. On the way, we had a treat of phở. "Wonderful!" my 74-year-old mother chuckled, and my children laughed in response. It was not clear whether they were thinking of their safe home-coming or of the steaming, appetising food before them.

Whatever my family were thinking, peace must have been topmost in their minds. And peace was in my mind when I was covering Operation Homecoming — the hand-over to the United States a total of 591 American prisoners of war, from privates first class to colonels.

The operation took two months — February-March 1973 — and the various transfers were made at Gia Lâm Airport, Hà Nội. In batches, the POW’s were brought from "Hilton Hà Nội", the name given by the Americans to the French-built central prison next to the Court House in the heart of the city. Neat in new grey uniforms issued by the Vietnamese authorities, they were lined up at the apron.

As their names were called, they stepped forwards one by one, fell into line, and marched towards a waiting C-141A Starlifter. Moments later they were airborne and out of sight. I brought my five-year-old daughter to Gia Lâm several times. It was not my intention to show Kiều Sương some of the Americans who had "scared" her and hundreds of thousands of other little children with their planes and bombs. I only wanted to catch in my daughter’s limpid eyes a reflection of the clear blue sky above from which dark clouds of war were gone for good, and to show her that beyond the horizon was a greater world for her to explore.

But my optimism was short-lived. Like most people, I could not foresee that despite the formally signed peace agreements, the war in Việt Nam, then beginning to be "de-Americanised", would drag on for two more years in the south, until the collapse of the RVN government in Sài Gòn in April 1975.

From Dockyard to Maiden Voyage

In 1991, Đỗ Phượng, who by then had replaced Đào Tùng, put the Vietnam Weekly and the Vietnam Hebdo under VIETNAM PRESS, a proposed non-governmental information, press, and publishing group, the first of its kind in the country. In fact, as early as 1988, Đỗ Phượng had represented both the VNA and the VIETNAM PRESS at a Warsaw conference for heads of news and press agencies from the socialist countries.

One afternoon in March, we moved to VIETNAM PRESS headquarters at 79 Lý Thường Kiệt Street, which also housed the monthly Vietnam Pictorial. There were only eleven of us to produce the two periodicals. It was raining, but the general spirit was high.

"Rain while moving house is a good omen!" one female reporter quipped. I shared her optimism, but read that auspicious sign in the determination with which we pushed and pulled cartloads of desks, chairs, filing cabinets, typewriters and whatever we could snatch without remorse from the Foreign Desk.

Our new home was on a floor newly added to an ageing building. It was spacious and full of light, ideal for an open-plan newsroom. The only trouble was that the walls were paper thin and there was no ceiling, which turned the place into an oven in summer and a freezer in winter. But at least we now had a place to call our own. No need to say how pleased we were to embark on a new project.

For three months, while carrying on with the usual business of the two weeklies, we sweated over preparations for a regular newspaper in the English language, the first of its kind in reunified Việt Nam.

We discussed at great length the title of the future paper.

Finally, Vietnam News (VNS) was selected from a field of a dozen entries including Hanoi Post and Hanoi Times. We liked the name because it had a national ring to it. The actual nuts and bolts of daily operation were harder to tackle, with lots of trial and error. Compared with the weeklies, the daily was a little more technically "advanced". Thanks to a stand-alone computer loaned by the colleagues downstairs, word processing and layout were no longer a major concern. Yet, the typist sometimes had to change font sizes to make up for miscalculations by the layout artist, who only trusted his pencil and ruler. The result was that a page would more often than not look like a topographical map.

Transmission was the biggest headache for it was essential for communication with the southern branch office. As the paper was to hit news stands in Hà Nội and Hồ Chí Minh City simultaneously, the finished layout had to be sent page by page to our people there for immediate reproduction. This could be done by fax. Photos were different; they had to be telexed for good quality. Somewhere along the way, our inventive boys hit upon an ingenious solution by rigging up a system of modems and software with which they were able to transmit both texts and graphics digitally by telephone line. The process was slow but quality was guaranteed. Manpower posed an almost insurmountable problem.

Among the original group of eleven running the head office in Hà Nội, only five were trained in English and three in French. They were responsible for the editorial aspect of the three publications, which included reporting, translating, subbing, editing, as well as proof reading. The three other staffers looked after printing, distribution and advertising. I was lucky to have with me Nguyễn Tri Bình, a young demobilised soldier who doubled very ably as reporter and translator; Tạ Quang Tuyến, the tireless office factotum; Phạm Thị Thủy and Nguyễn Thanh Hà, our only female reporters and "errand boys",and Đặng Văn Hiến, the copy editor with the Vietnam Hebdo and an associate of mine during my Cambodia interval.

We only had four in the branch office in HCM City – two very enterprising young men, Nguyễn Tiến Lễ and Lý Chánh Dũng; and two not-too-young ladies, Nguyễn Thị Yên and Trịnh Thị Ninh, both wise in the ways of the market economy. They alternated between reporting, printing, distribution, and advertising.

We emerged ourselves in our labour of love, slurping down a bowl of instant noodles and napping on our desks during lunch break, waiting bleary-eyed for the signal from the HCM City office that said the paper had been put to bed safely.

We were in seventh heaven when, in the small hours of June 17, the first edition of the Vietnam News appeared at the same time in Hà Nội and HCM City. This was a momentous event, the crowning of months of trial and error. There was no end to celebrations at the head office in the iron-roofed top-floor newsroom. The staff was ecstatic over copies fresh from the printer’s, some had stayed with the paper from the time it went to press until the wee hours of the morning when it was picked up by newsboys. Congratulations between head office and branch office and from well-wishers kept the wire hot throughout the day. It was mid-summer. The office was a regular oven, which caused many of us to cast off our shoes, sandals and even shirts, giving rise to our so-called "barefoot tradition".

*Published by Vietnam News Agency

Publishing House, 2016

Not for Sale