Life & Style

Life & Style

Lịch Sử Thư Pháp Việt Nam (The History of Vietnamese Calligraphy), a book by 31-year-old researcher Nguyễn Sử, has just been published by Nhã Nam Books.

|

| Researcher: Nguyễn Sử with a historic artefact. |

Lịch Sử Thư Pháp Việt Nam (The History of Vietnamese Calligraphy), a book by 31-year-old researcher Nguyễn Sử, has just been published by Nhã Nam Books. It is said to be a work of high quality with lots of illustrations and persuasive data by experts. Sử has been a calligrapher since the age of 10, when he started learning the Han Chinese language and script at a pagoda in Ninh Bình Province. He has joined various calligraphy exhibitions at home and abroad. He works full time as a researcher at the Việt Nam Social Sciences Academy and teaches calligraphy during his free time. Lê Hương spoke to him about his work:

Please tell us about the content of your book.

It is divided into two parts. The first is a general overview of the history of calligraphy in countries like China, Japan and South Korea.

The second part explores the development of Vietnamese calligraphy, starting from engraving documents on artefacts like bronze drums, stone stelae during the Đông Sơn Civilisation (700-100 BC) up to the Later Lê Dynasty (1428-1789). It also studies the development of different styles of Vietnamese calligraphy.

How did you gather data for the book? How long did it take?

I spent almost four years on the book. I accessed several libraries and various other sources for information on calligraphy in the past. It required a lot of time and patience.

Another main task was travelling to many areas to copy stelae to print on the book as illustrations for different styles in calligraphy.

Were there difficulties? Please share with us a few memorable incidents.

A lot of difficulties resulted from the fact that ancient objects had been wildly looted in localities. So locals doubted my work because they did not understand what I was doing. I had to prepare a lot of papers to identify myself and my job. But sometimes, they demanded more than the papers I had. At the same time, I also received a lot of support from concerned agencies from the central to local levels.

I remember most a trip to the northern province of Cao Bằng to copy a stele by Lê Lợi (1385-1433). I had to climb up hills and walk through streams as the stele is located in a remote area. It took me several days to erect a bamboo scaffolding of 25m high to climb up the stele. It was scary to climb up the scaffolding to make a rubbing with the stone inscription and it was even more scary when it rained. But God blessed me. I finally succeeded in making a copy of the “document”. A local resident gave me a tasty boiled chicken as a gift. I felt very lucky then.

What are some of your findings about the origins of calligraphy in Viet Nam? Are there any similarities and differences between Vietnamese calligraphy and the art in China, Japan and South Korea?

As other researchers have also noted, the art of Vietnamese calligraphy was born at the same time as the introduction of Han Chinese characters into Việt Nam. The art of calligraphy in Việt Nam in general has developed at the same speed as in other countries in the region that use ideograms.

The Vietnamese people have developed their own styles of writing, like those used during the Lý (1009-1225) and Trần (1225-1400) dynasties.

Each dynasty had its own popular way of writing calligraphy and there have been many distinguished calligraphers throughout our history.

Under the Lý dynasty, the preference was for the style used by China’s Tang dynasty (618-907). Under the Trần dynasty, the stronger influence was China’s Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties.

Which was Vietnamese calligraphy’s golden period? What were the factors involved?

The periods that left behind the most historical documents on calligraphy were the end of Lê Trung Hưng (1533-1789) and the beginning of the Nguyễn dynasty (1802-1945). These periods can be considered as the golden time of Vietnamese calligraphy.

However, I still highly appreciate the art value of calligraphy in the Lý (1009-1225) and Trần (1226-1400) dynasties. Though there are not many historical documents mentioning the art of calligraphy under these two periods, what we can find is a stable foundation for calligraphy, which was as good as those in other countries.

Please tell us about your daily work? What will you do next?

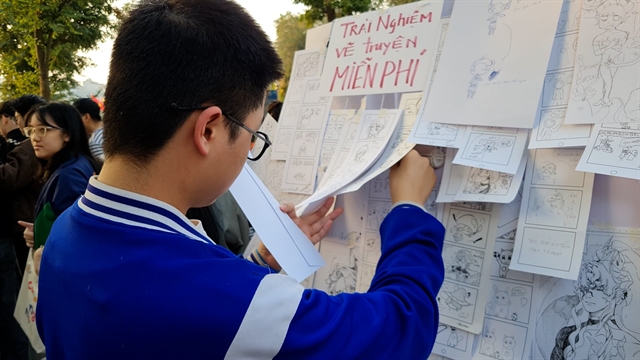

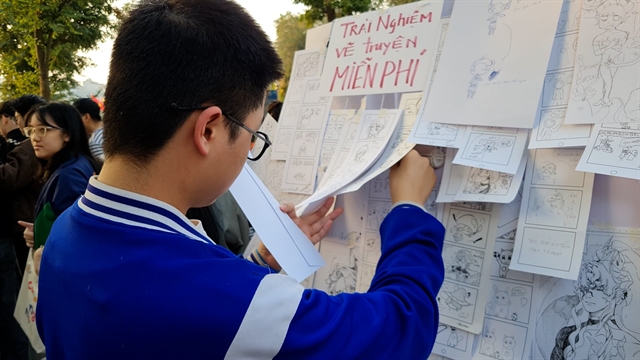

Everyday, I read books, I mostly research Buddhism. At weekends, I teach calligraphy and Buddhism to some youngsters so that they can understand Buddhist aspects of the Vietnamese lifestyle and practise calligraphy.

I plan to write one or two more books, hopefully this year and the next. That’s my plan. Please wait and see whether I am able to realise them or not. — VNS

|

| Dedicated: Nguyễn Sử climbs up the walls of a cave in Lạng Sơn Province to make a rubbing of a stele. Photos courtesy of Nguyễn Sử |