Opinion

Opinion

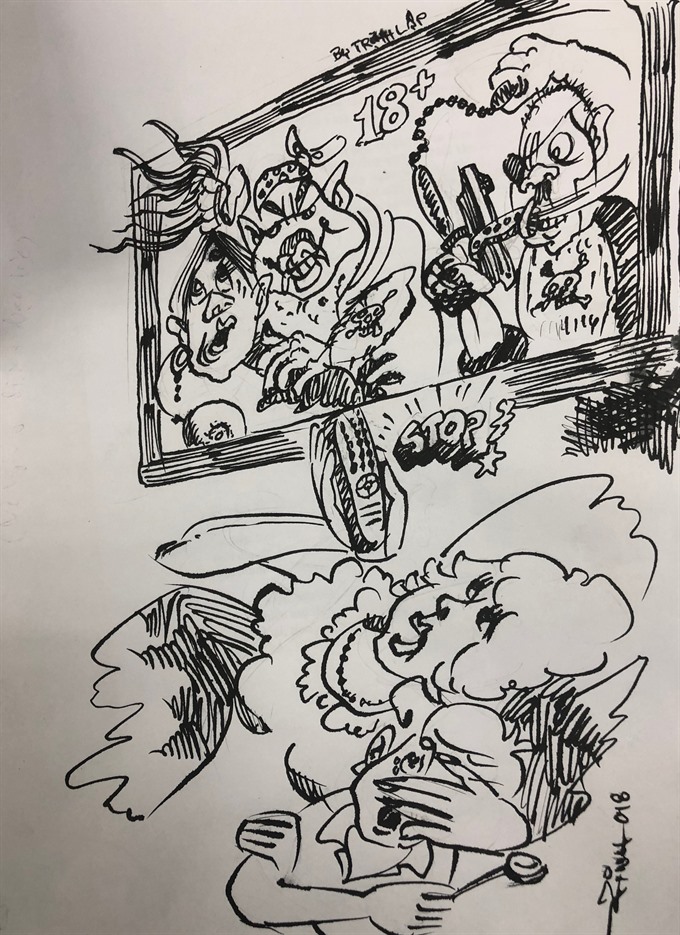

Sensationalised and graphic depictions of prostitutes, gangsters and everyone in between have been a big part of Vietnamese movies and television films for the past two decades.

|

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

By Linh Do

On a recent Sunday night, pedestrians flooded the area around Returned

“It’s because it’s been raining hard, locking people inside for the past few days,” a parking lot guard explained to a friend.

The sight of crowded streets, where too many people jostle for too little space in an endless circle of shopping, eating and drinking, brings to mind something French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss said in one of his last interviews before he died in 2009.

“There is today a frightful disappearance of living species, be they plants or animals,” said Levi-Strauss. “And it’s clear that the density of human beings has become so great, if I can say so, that they have begun to poison themselves…”

How far we have begun to poison ourselves is a matter of debate. As far as visual culture is concerned, I think audiences must be feeling quite sick by now.

Turn on a TV channel these days and you are treated to one dish after another of loudness, vulgarity and mediocrity: endless singing and dancing reality shows, dragging sensational local and foreign soap operas and melodramas.

Here is a scene from episode three of director Mai Hồng Phong’s 30-episode series Quỳnh búp bê (Quỳnh the Doll) about prostitution:

Two pimps wait outside a hotel room for any sign of trouble from Quỳnh, who has been kidnapped and sold to their brothel in disguise and is now being forced to serve a client for the first time. The pimps hear the client slap Quỳnh and rush inside. The client angrily shouts, “Did you two bring a pregnant hen here to fool me?!” It turns out that Quỳnh, who was expected to fetch a high price because she is supposed to be a virgin, had been raped before she was trafficked and is already four months pregnant.

Sympathy for real victims of human trafficking aside, I’m fed up with the sight of sex workers and gangsters in Vietnamese films these days.

Sensationalised and graphic depictions of prostitutes, gangsters and everyone in between have been a big part of Vietnamese movies and television films for the past two decades. The war classics such as Đặng Nhật Minh’s Bao giờ cho đến tháng 10 (When the 10th Month Comes), with their compact symbolism, have faded away.

What is left now is mostly forgettable stuff ranging from state-owned studios’ laughable attempts to combine social instruction and entertainment, to the private sector’s trash.

An example of the state-produced unintentional hilarity is Sống cùng lịch sử (Living with History), produced by Viet Nam Feature Film Studio, in which a group of youngsters travel with their backpacks to Điện

An example of trash is Charlie Nguyễn’s action film Bụi đời Chợ Lớn (Chinatown) which dishes out violence from beginning to end with such relish that the film was banned. The censors found the violence unrealistic. Gangs fight continuously on the streets without police intervention.

The first six episodes of Quỳnh búp bê aren’t unrealistic trash, at least. Filled with brutal language, female objectification, rape, torture and terror, the series is a decent portrayal of the slave-like existence of prostitutes. The film is based on the true story of a former prostitute named Quỳnh herself.

In its dark moments of sheer brute force against women, the film calls to mind historian Gerda Lerner’s The Creation of Patriarchy, which says that it was through the control of women that men first learned how to control other men. Human slavery originated in the exchange of women in marriage among tribes. The first slaves were women of tribes conquered in warfare.

Nevertheless, all things considered, one wonders whether filmmakers’ sincere intention to reflect reality has resulted in a series of images that actually work to fossilise a woman’s identity, rendering us all perpetual victims.

Life is so transient and precious that we must immerse in it fully, while still striving to produce and appreciate those aspects of human existence that occur outside the realm of daily life and banalities—that is to say, art. Yet as a woman and an observer of films and culture, I feel robbed.

The ubiquitous camera and films force me to see countless paralysing images of what is supposed to be me: from Bao giờ cho đến tháng 10’s impeccable classical icon of a heroic, patriotic mother to Quỳnh búp bê’s vulgar pictures of girls raped and sold.

Explaining the sex and violence in his film, director Phong told local media that viewers might be shocked, but such was reality. “When we talk about corruption, we need specific numbers,” he said. “When we talk about prostitution rings and disgusting crimes that need to be eliminated, we want audiences to confront the images directly.”

Not necessarily. There are certain things that the eyes and mind can’t take. The show is what happens when we push the limits too far. After receiving negative backlash from viewers, Viet Nam Television channel 1 (VTV1) has recently stopped airing Quỳnh búp bê, even though it tried to warn viewers by labeling the series “18+” from episode five, making the film the first one to be so classified on VTV.

Unfortunately, the show has joined the list of trash entertainment that became a "martyr" in the public eye when it was censored for excessive shows of sex and violence.

A common response to VTV1’s decision is to argue that the series could be aired during a later time slot and on a channel more appropriate for adult films. This would create a sophisticated tiered viewing system similar to those in developed countries, where you can pay to watch whatever you want.

Like the cheeky MasterCard’s “Priceless” commercial, I say, in earnest, “There are some things money can’t buy.” And here we see two things that it can’t buy: justice and creativity.

First, prostitution and other social ills should be treated as realistically and seriously as possible. They had better be captured in investigative journalism and documentaries, not a fictional TV series with a sensational soundtrack that can be watched online under VTV’s “entertainment” section like Quỳnh búp bê.

Second, writers and artists of this century seem to be walking behind scientists in terms of deep originality. While scientists are searching for continuing surprises of the universe, many artists still think that the highest ideal of art is to reflect human reality as it is, rather than as what it could be.

Vietnamese filmmakers tend to play out the same old drama between men and women in familiar genres instead of trying something different and imaginative, like animation. After getting an eyeful of human beings around

When one’s heart honestly cares about justice, and one’s mind tries to be really creative, then films will find their rightful places without fuss, without the need for conscientious but shallow classification: Adults watch documentaries about social issues and do something about society, and children have good animation to see.

Phạm Thu Hằng, an independent documentary filmmaker, supports artists’ free expression and experimentation with what is traditionally considered taboo such as sex, homosexuality or incest. But artists should justify why their characters cross the limit.

Hằng said in Phan Đăng Di’s Bi, đừng sợ! (Bi, Don’t Be Afraid!) for instance, the sexual attraction between a woman and her father-in-law looked like mere lust than anything of substance.

As for me, do I want VTV to resume airing the next episode of Quỳnh búp bê? No! With all due respect, let everything stop here. It’s time for a break, a blank, silence. Everybody, move over please. VNS