Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

In recent weeks and months, there have been umpteen reports of foreigners of seemingly all stripes in Việt Nam struggling to renew their visas to remain in the country, whether they hold tourist visas, legitimate labour visas and work permits or less legitimately acquired paperwork.

|

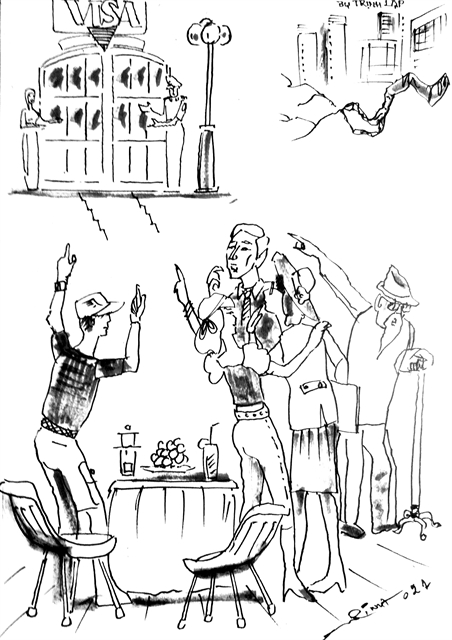

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

By Peter Cowan

The phrase “Think global, act local” has popped up in my head again and again over the last few weeks and months.

More specifically, I’ve been thinking about the first half of the maxim oft-repeated by jargon-loving marketing executives and tree-hugging UN types alike.

Thinking global, to me at least, means taking a step back and making sure you don’t miss the forest for the trees, to use yet another cliché.

Those two words have arrived in my head whenever I’ve stumbled across one of the hundreds (if not thousands) of social media posts about what some have called Việt Nam’s visa “crackdown”.

In recent weeks and months, there have been umpteen reports of foreigners of seemingly all stripes in Việt Nam struggling to renew their visas to remain in the country, whether they hold tourist visas, legitimate labour visas and work permits or less legitimately acquired paperwork.

Part of why so many have faced these problems is the passage of a new decree into law in February making it considerably tougher to qualify for an “expert” visa, while fears of illegal foreign arrivals being a COVID-19 risk has almost certainly also played a part.

It should be noted that enforcing these regulations is part of Việt Nam ensuring its laws match its development and security needs, and anyone can see the country has developed rapidly in recent years, so changes are a part of that, making the term "crackdown" a touch dramatic.

Nonetheless, the changes have caused a huge deal of anxiety and vociferous debate among foreigners in Việt Nam who fear being forced to leave the country, specifically about its purpose and fairness.

The issue has even made local and regional headlines, with anonymously interviewed foreigners given platforms to vent about their visa woes.

While I genuinely sympathise with anyone faced with the possibility of uprooting their lives in the middle of a pandemic, to me the debate among foreigners and the media coverage has largely lacked global thinking.

No comparison

Consider, pre-pandemic of course, the process for a Vietnamese citizen to acquire a visa to visit my home country, the UK.

A friend told me she had to supply bank statements proving she had enough cash to support herself on the trip, proof she had a job in Việt Nam that was giving her time off and proof she was in a relationship with her partner, whose family she was to stay with. On top of that, her partner’s family had to provide evidence that they had sufficient income to support her during the trip.

Meanwhile, a British national who wants to visit Việt Nam for two weeks simply needs to show up with a valid passport and flight booked out of the country.

No wonder the entire experience of applying for permission to visit left my friend feeling “rubbish”.

There is truly no comparison between the two situations, but I’m not trying to make the juvenile point that if person A has to go through something tough, then so should person B.

It’s shameful to admit, but having read far more about immigration and visa problems in the last few months than ever before, the changes underway in Việt Nam have finally made me step back and think more globally about just how unjust immigration policies can be in the western world.

I knew on an intellectual level how tough it was to migrate and travel for many people, and I certainly shared in my friend’s pain about the hoops she was being forced to jump through, but embarrassingly it took a bombardment of complaints from self-styled “expats” to make me reexamine my feelings on travel and migration.

The very idea of passports and visas, at least in the modern sense, comes from World War I when governments felt they needed to know exactly who was coming and going within their borders.

While that’s a simplistic, one-sentence rundown of a complex global system, it does still beg the question: why does it still have to be this way in times of peace?

You don’t need to be an international migration scholar to know about the dangers millions of people face around the world just because of a few squiggly lines on a map; you just need to flick on the news once in a while.

The Essex lorry tragedy of late 2019 is a prime example of the tragedies that can occur when that very human desire to migrate forces people to collide with seemingly impenetrable barriers just because of where they happen to have been born.

Perspective

With just a little bit of global thinking (and I’m certainly no galaxy brain), it’s a lot easier to put Việt Nam’s visa changes into perspective.

Yes, there are still problems with the opacity of immigration procedures here, the manner of immigration law enforcement and the consistency of that enforcement, and I’d wager many in officialdom would agree improvements could be made.

In addition, immigration policies are often designed on a reciprocal basis, so as things change for the better for some, there is hope they can change for the better for all.

Things aren’t perfect here, but the fact of the matter is westerners in Việt Nam are still being treated with far more leeway and compassion when it comes to immigration than citizens of the global south face in the west.

Are newspaper front pages demonising foreigners? Are popular media personalities referring to migrants as “cockroaches”? Are immigration officers dragging people out of their homes and throwing them into vans to be carted off to detention centres?

Immigration is imperfect everywhere and this may come as scant consolation to those westerners being forced to leave Việt Nam before they wish to, but a touch of global thinking and some realism may provide a modicum of solace.

As guests in this country we won’t ever change its laws or customs, and rightly so, but there’s nothing stopping foreigners from raising their voices in their home countries.

Why not demand more compassionate coverage of migration from our media? Why not demand our politicians reject tribalism and embrace just migration policies? Why not demand our friends and families take a closer look at their country’s immigration system?

You may think I’m being naïve to expect such demands to make a difference, and you’d have a point, but a more equitable global migration system is never going to come about if the only people who want one are migrants.

So why not think globally and act at home? It’s certainly a better long-term solution than looking for the next country with lax entry requirements to chance your luck in. VNS