Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

The Association of Cultural and Culinary Societies of Việt Nam recently proposed hosting a festival dedicated to bánh chưng and bánh dày, honouring Lang Liêu as the “founding father” of all Vietnamese culinary traditions.

|

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

Last week seemed to go on for longer than most, despite a national holiday commemorating the legendary “founding fathers” of Việt Nam falling right in the middle of it. The acts and deeds of the Hùng Kings have long been regarded as legend, though. But if you found yourself at Kings Hùng Temple in Phú Thọ Province during the week, you would have found monuments to all of these Kings, legend or not.

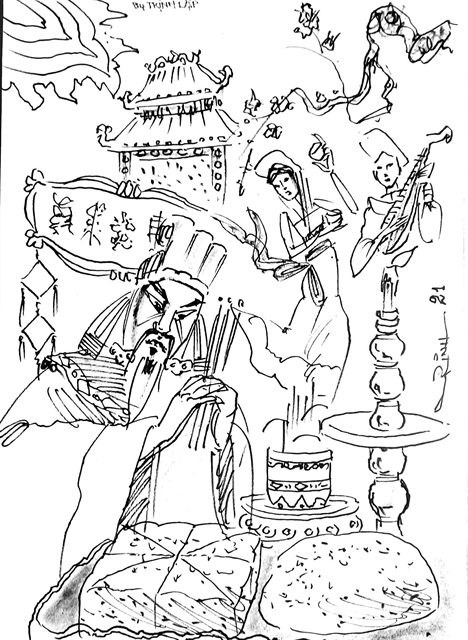

One of the most popular Hùng Kings was the 7th, Hùng Chiêu Vương, who won a challenge his father arranged among his 20 sons to find the most exquisite items the land possessed, as an act of filial piety. Lacking the resources to venture far and wide, he instead created a dish that rich and poor alike could indulge in - bánh chưng and bánh dày sticky rice cakes. The simple yet meaningful square cakes resemble the earth, with green foliage, the rice and beans the forest, providing meat, and white sticky rice the sky.

Legend has it that Lang Liêu was a prince, but he lived poorly and lost his mother early in his life. When his father the King arranged the contest, Lang Liêu had no means to fetch rare and precious items from far beyond. Legend also has it that he had a dream, where a deity came to tell him that, “Out of all things on earth and under the sky, there’s nothing more precious than the rice grain. Rice nurtures people to become strong, and you’ll never tire of it. Now, take the sticky rice to make two types of food: one square and the other round. Then add good ingredients inside, and wrap it in green leaves that hint at the immense gratitude for your parents’ giving birth to you!”

It’s a story not unlike David and Goliath, with sincere and simple ingredients made with love and gratitude winning over rare and costly items that show off one’s power and capacity. Love and gratitude coming in simple yet delicate food is not only a good story to tell, it also won over the taste of King Hùng VI.

The Association of Cultural and Culinary Societies of Việt Nam recently proposed hosting a festival dedicated to bánh chưng and bánh dày, honouring Lang Liêu as the “founding father” of all Vietnamese culinary traditions. A roundtable discussion is set to take place by the end of April, where those attending will decide on a day to commemorate Prince Lang Liêu, who later became King Hùng VII (either on his birthday or his death anniversary).

“No, no festival, no public gatherings!” responded one netizen to a post in a closed culture-culinary group. “No public gatherings or festivals until the pandemic is over. We are in no rush!”

“No to yet another festival, which is totally made up and where there is no concrete proof about the king’s birthday or death anniversary,” read another comment.

Those who oppose the idea of celebrating yet another festival touched on the legend of bánh chưng and bánh dày, which were first recorded in Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái, or the “Selection of Strange Tales in Lĩnh Nam”, a 14th century semi-fictional work collected and written in Han Chinese script by Trần Thế Pháp. A note in the text states that the stories were picked from myths and legends popular in the Lĩnh Nam area.

“Taking a myth and turning it into a specific activity, and even turning a mythical figure into a real-life person, just means you’re making something up and calling it history. This is unacceptable,” wrote one member of the Culture-Culinary Society, who said his opinion would be elaborated upon in a paper to be presented at an upcoming discussion.

He also pointed to a view expressed by acclaimed historian Trần Quốc Vượng, who argued that bánh chưng and bánh dày have now become regular dishes around Việt Nam and are no longer restricted to religious offerings, as was once the case.

In an essay, Vượng wrote that the square shape of bánh chưng was not the only shape it had, and questioned whether the round sticky rice represented the sky. Việt Nam was not the only country to make sticky rice into round buns, as Japan has mochis, or to make sticky rice into stuffed food wrapped in green leaves, which southern China has examples of.

“So don’t think these were created by ancient Việt people, or are only authentic in Việt Nam,” was the message I got from reading the essay.

But I must disagree on each and every point the essay was trying to make.

Other cultures and other countries may share similar food with Việt Nam, but that doesn’t mean our tales of bánh chưng and bánh dày are questionable, or that our tradition is to make it for special occasions and offer it as a way to express gratitude to the ancestors.

A new festival could be a forum for neighbouring regions or countries to share their traditions and for Vietnamese to taste similar yet different dishes from elsewhere. But such a festival could easily become too commercialised and the original taste and flavour may be altered.

Only in Việt Nam is the size, the shape, and the stuffing so different and colourful: you have the black sticky rice cakes of the Tày ethnic people in the north of the country, and the red sticky rice with the sweet flavour of sugarcane in the stuffing, in addition to the popular green colour.

You can see a long tube of sticky rice from the northern mountains, and dishes in villages deep in the Mekong Delta, which they make instead of the square cake versions.

Chinese people living in Việt Nam also have a variety of sticky rice and seafood stuffing called bakchang.

While the story and its meaning may, again, come from legend, actual treats are made every year by nearly everyone. In real life, what speaks to the power of any myth or legend more than having people make real food to keep a tradition alive. If your scientific-logical mind needs proof, then go to real communities and meet people who may not have time to argue about the origins of the dish but who make it best.

Watch them first, enjoy the treat, and then we’ll talk about logic later on.

We can all wait until the pandemic comes to an end! Until then, wash your hands and wear a mask! VNS