Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

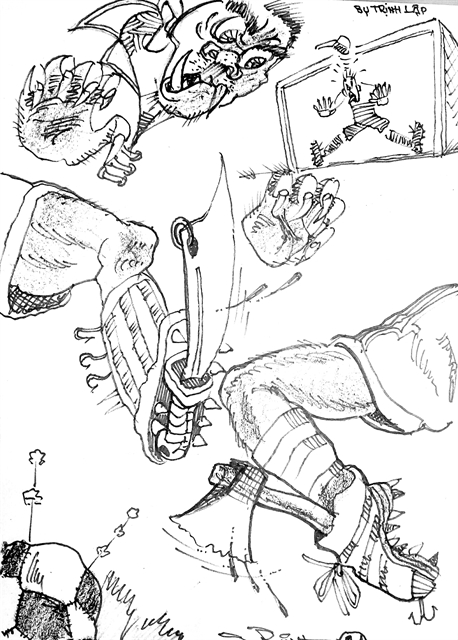

A horror tackle by HCM City FC midfielder Ngô Hoàng Thịnh left Hà Nội FC midfielder Đỗ Hùng Dũng with a broken leg and the prospect of at least six months on the sidelines.

by Thanh Hà

|

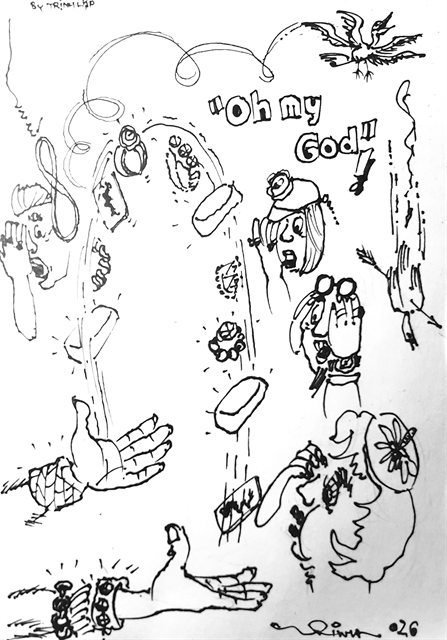

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

A horror tackle by HCM City FC midfielder Ngô Hoàng Thịnh left Hà Nội FC midfielder Đỗ Hùng Dũng with a broken leg and the prospect of at least six months on the sidelines.

The tackle has been massive news in both local and international media, reminding people of similar tackles from years ago that also made headlines.

Defender Trần Đình Đồng from Sông Lam Nghệ An lunged into defender Nguyễn Anh Hùng in 2014 and broke his leg.

Hùng lost consciousness on the field and was rushed to hospital. He spent nearly a year in rehab before returning to the pitch.

A year later, defender Quế Ngọc Hải from Sông Lam Nghệ made a similarly reckless tackle on Trần Anh Khoa from SHB Đà Nẵng.

Khoa went down with ligament damage that ended his career at the tender age of 24.

And June 6, 2020, was a sickening day for midfielder Nguyễn Hải Huy from Quảng Ninh, as he was on the receiving end of a nasty challenge from Hồng Lĩnh Hà Tĩnh defender Phạm Hoàng Lâm. Again a broken leg was the outcome, which left Hải on the sidelines for nine months.

“The sight of Dũng’s bent leg brought many to tears,” said Hà Nội FC defender Đỗ Duy Mạnh, who has only recently returned from months of rehab for ligament damage. “Injuries like that are the stuff of nightmares for players.”

The national team star sent out a message: “Everyone wants to win, every player wants to do their best. Yes, do your best, but don’t destroy your opponent. Football is just a sport, but for many it also feeds their family.”

Thịnh was given a record punishment - fined US$1,700 and suspended until the end of the year. He also has to pay for Dũng’s medical care.

While heavier fines and longer suspensions are the subject of much discussion, professional ethics clearly need to be added to training programmes at clubs.

“Violent play in the V.League is like a cancer, growing season after season,” said Trần Hữu Nghĩa, a member of the Việt Nam Football Fan Association. “We go to watch our beautiful game and encourage fair play, not violence.”

“We could wipe this out if the VFF and the VPF impose really strict bans and referees do a good job. We shouldn’t show any mercy for players guilty of such play.”

Trần Văn Hồng, president of the SHB Đà Nẵng FC Fan Club, agreed. “Players should focus on how to improve their technique and skills and not use violent play to get on top of an opponent,” he said.

“Clubs and league organisers should impose stricter punishment, like longer suspensions and salary cuts. Only when players personally suffer will they stop such behaviour.”

Nguyễn Văn Mùi, head of the VFF’s Referee Council, stressed the role of referees in stamping out violence on the pitch.

“Concessions on the referee’s part and a lack of punishment can sometimes lead to aggressive fouls,” he said. “If the refs can manage the game well, they can stop it from descending into violence.”

“If a player is shown a red card the first time he commits a brutal foul, he’s likely to change his ways. But if he gets away with it, he’s going to do it again and again.”

More than fines and suspensions, education is needed to stop overly-aggressive play.

“This is the last straw,” said pundit Nguyễn Quang Huy. “Clubs must take responsibility for educating players as soon as they join the club. Coaches and clubs need to be really strict and impose heavy fines on dangerous tackles. Players will understand the consequences and not make the same mistake twice.”

Pundit Đoàn Minh Xương said he didn’t necessarily blame Thịnh for the incident because it comes back to the poor training of players.

“When I visited French club Olympique Lyon many years ago, I saw the lessons they give to their U13 and U15 squads,” he said. “They were told they could become stars if they were talented, but with training in technique and behaviour everyone can succeed.”

“The lessons included how to behave with teammates, fellow players, the media, and supporters.”

“In Việt Nam, many coaches push their teams to play hard and aggressively to win, but not all of them tell their players how to avoid injuries or injuring their rivals.”

“Players are also human. When the final whistle blows, they’re friends. Teaching them ethics and good behaviour are the best things to do for their career and the safety of others.”

Coach Hoàng Anh Tuấn suggested players learn about the law and be aware of their profession.

“I don’t think Thịnh intended to hurt Dũng, because they have no dispute,” he said. “In life, no one tries to beat someone else for no reason. Thịnh’s playing style is sometimes too physical.”

“Many players can’t distinguish between playing the game hard and slipping into violence. Once they understand, they would never break the rules.”

According to the former national U18 team manager, players should be taught about such issues from a young age. Together with technical training, they need to be educated about when physicality goes over the top.

“No one can predict when an injury might happen in sport,” he said. “We need to tell them to be competitive, but with controlled aggression.”

Khoa, who is now a coach, shared his thoughts.

“The first thing I tell my players is to keep your legs safe and also the legs of your opponent,” he said. “Anyone can go out there and just be aggressive, but the point is to play cleanly and fairly. This is how we attract interest in the game.”

This is also what Đoàn Nguyên Đức, the owner of Hoàng Anh Gia Lai (HAGL) JMG Football Training Centre, told his players, who he considers to be his sons, “Don’t play ugly on the pitch,” is the message.

“Don’t play dirty football. Players must learn to be a good man first, before training to be a good footballer.”

Such advice has become one of the mottos of the JMG centre, and it’s why HAGL are the most loved team in the country. Their players win the hearts of millions of supporters win, lose or draw. VNS