Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

Tết traditions: How can we respectfully preserve or adjust time-honored traditions?

|

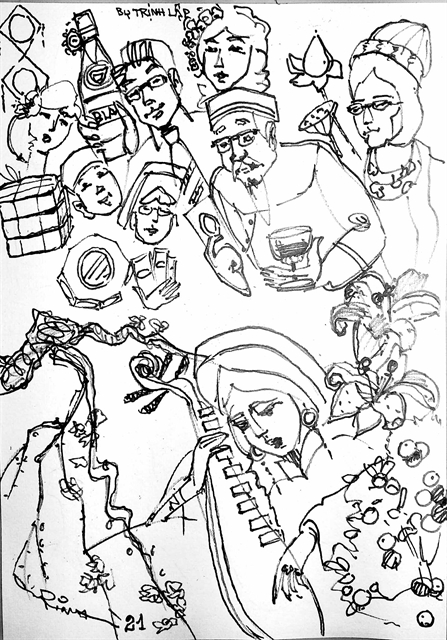

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

The recent Lunar New Year marked the end of the Year of the Rat and everyone was looking forward to the Year of the Buffalo (which fell on February 12 this year) with high hopes for better times.

Every family had a lot to do in preparing to welcome in the New Year, and the week-long process was exhausting, taking up a lot of what was the longest holiday of the year.

Given that most families decided to stay home due to the recent COVID outbreak, everyone had been preparing for Tết (the Lunar New Year festival) since the first Tết-related ceremonial offering on the 23rd day of the last lunar month. This meant at least 10 days of just festivities and the preparations involved.

Because of how demanding the workload can be preparing for Tết, some families looked forward to getting away to escape from the mundanity of it all. Modern families sometimes do the minimum in terms of ceremonial offerings and escape to a sunny place to relax.

One common tradition is the burning of joss paper as a way to send money and goods to the ancestors or relatives in the afterlife. One group, it seems, went to sleep while burning joss paper to farewell the Kitchen Gods, and when their house caught fire they perished in the ashes.

Apart from such upsetting fire hazards, burning votive offerings also has a serious environmental impact, affecting not only respiratory systems but also emitting harmful gases. The more one wants to send to the ancestors, the longer the burning takes and the greater the impact.

Another beautiful tradition -- buying festive trees for Tết -- also comes with environmental issues. Besides cherry blossoms and kumquat trees, many other flowers are sold to beautify and brighten up the home with new spring energy.

Many farmers spend long periods ensuring they can sell their most beautiful branches and earn a profit. But as I passed by deserted flower markets during Tết, many trees and plants were still on site, wasting not only the efforts of the farmers and the natural resources involved but also creating yet more waste to be disposed of post-Tết. And since flowers only bloom once, those that are bought are also discarded as soon as the holiday ends, adding yet more waste.

The Western tradition of buying pine trees for Christmas has also been criticised for its negative environmental impact, so some people have begun to replace real trees with DIY trees made from recycled materials, which can still bring a festive feeling to the home. Such thinking is yet to reach Việt Nam, and it’s hard to imagine a time when alternatives to festive trees are widely accepted.

The third negative element is the amount of food and food waste created. Some blindly follow tradition, with many glutinous rice cakes made and whole chickens boiled. Since every family prepares the same feast, one can’t help but get sick of eating the same dishes at least six times throughout Tết. After those festive days comes the pressing issue of food waste, with no one working towards getting leftover food to those who really need it.

The making of ceremonial offerings is an arduous task. Traditionally, as the official Tết holiday covers four days, including New Year’s Eve and the first three days of the New Year, each day includes at least one ceremonial offering. These include one to farewell the passing year and another to celebrate the coming year, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, and the last one on the third day to mark the ending of Tết. Add to that the one on the 23rd day of the last lunar month.

Since each feast includes multiple dishes, preparations can run throughout Tết, which is supposed to be a time of rest and bonding with families and friends. Of course, people nowadays no longer conform to every single ceremonial offering, but this still creates externalities like incense production and smoke that does damage when inhaled.

Keeping traditional values is important, as respecting the ancestors is ingrained into Vietnamese values, mindsets and culture. But where can we draw the line between old and new traditions and treat them with due respect? How can we maintain a festive atmosphere while everyone is constantly concerned about preparations? Perhaps the younger generation may invent a new type of eco-friendly incense in the near future, or DIY cherry blossom trees could become the norm. VNS