Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

Trần Tố Nga said she is fighting for her life and for her family, and behind her are 3 million Vietnamese also affected by the toxic chemicals the US armed forces used in Việt Nam.

|

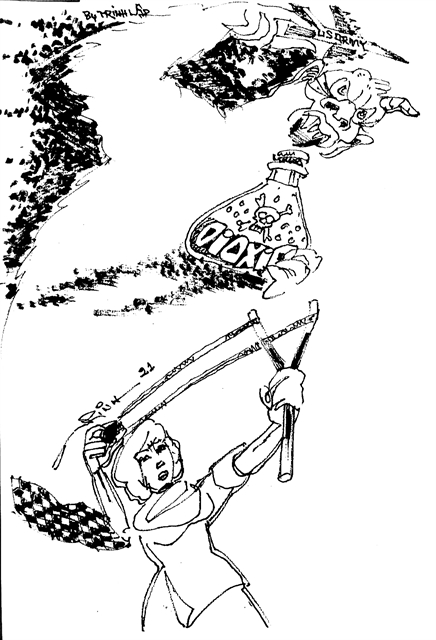

Illustration by Trịnh Lập

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

An international trial taking place in a Paris suburb is sure to touch anyone who has ever read about the deadly consequences of Agent Orange in Việt Nam.

Refusing to continue being a victim of the deadly chemicals sprayed by the US armed forces during the anti-American war in South Việt Nam, Madam Trần Tố Nga, 79, is taking giant American chemical producers to court in France.

Fifty-nine years after the first batch of Agent Orange defoliant was sprayed by a Huey helicopter to clear away jungle near the headquarters of the South Việt Nam National Liberation Front (NLF), Nga, who as a war reporter toiled away under the canopy, is now taking on 14 companies, including Dow Chemicals and Monsanto, in what she believes is the first ever ecocide court case.

It took six years for the court to agree to an initial hearing, scheduled for last year but deferred until January 25 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

She is fighting for her life and for her family, she said, and behind her are 3 million Vietnamese also affected by the toxic chemicals the US armed forces used in Việt Nam. Traces have been found in third and in some cases fourth generations of those who found themselves under the poisonous mist.

The US army sprayed nearly 20,000 US gallons (76 cubic metres) of chemical herbicides and defoliants on more than 31 square kilometres of jungle in southern Việt Nam, eastern Laos, and some parts of Cambodia between 1961 and 1973.

As a frontline reporter from 1966 until 1969 for the Liberation Press Agency of the NLF, Nga worked right where the most spraying was done. She was infected by dioxin, the most toxic chemical in Agent Orange.

She underwent tests at a lab in Germany and testified as an Agent Orange victim at the International People’s Tribunal of Conscience in Paris.

“Conscience” is what her long and arduous fight has been all about, and an army of lawyers have committed to helping her out over the years and promise to continue doing so for as long as she keeps fighting.

Her French lawyer, William Bourdon, reportedly told France’s L’Humanité newspaper that: “The stakes in this trial are considerable, on the judicial, symbolic and historical levels. This is the only such lawsuit to ever be initiated.” He added that there was a previously unsuccessful attempt to file a lawsuit in South Korea by a person who contracted specific health conditions related to the spraying of toxic chemicals by the US in Việt Nam.

Much support has come Nga’s way, with about 300 people defying the pandemic to demonstrate outside of the Crown Court of Evry town near Paris. The case received coverage in the French media, while the companies she’s standing up against have done their best to once again avoid responsibility and their own “conscience”.

The powerful multinational chemical companies have spared no expense in engaging the best attorneys for their defence team. They also know that time is ticking for an elderly woman nearing her 80th birthday and suffering from multiple ailments.

But Madam Nga is by no means alone. France’s top international lawyer, William Bourdon, who specialises in white-collar crime, communications law, and human rights, is representing her pro-bono. His expertise in defending victims of globalisation and crimes against humanity put him among the most powerful of international lawyers.

Sources familiar with French court procedures say that a time-consuming approach has been taken by the defendants’ attorneys. If the judge takes a dim view of the practices of the US corporations, he may well rule in Madame Nga's favour.

But if it can be shown that there is insufficient evidence proving she was in areas sprayed, such as work contracts or official job assignments, or if scientific tests have been insufficient and do not confirm a direct link between dioxins and human deformities and disease, the big corporates will win.

Much work has already been done, however. In the updated edition of “Dioxins and Health”, co-authors Dr Arnold Schecter and Dr Thomas A. Gasiwiecz write that major advances have been made in human epidemiology as well as in animal studies. It is this type of testimony that would support her case.

No matter how the court rules, though, Madam Nga’s bravery and self-righteousness in fighting ecological crime will mean she is triumphant nonetheless.

She told the Tuổi Trẻ newspaper that she was once asked by the defendants’ attorneys: “Both sides use whatever they have in war. Why make such a big deal out of it?”

Her reply was simple: “Is it legal to use chemicals?”

Nga’s fight is viewed by many as a David-vs-Goliath legal battle, but David shall win out, at least in the hearts of so many.

We shall see! VNS