Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

|

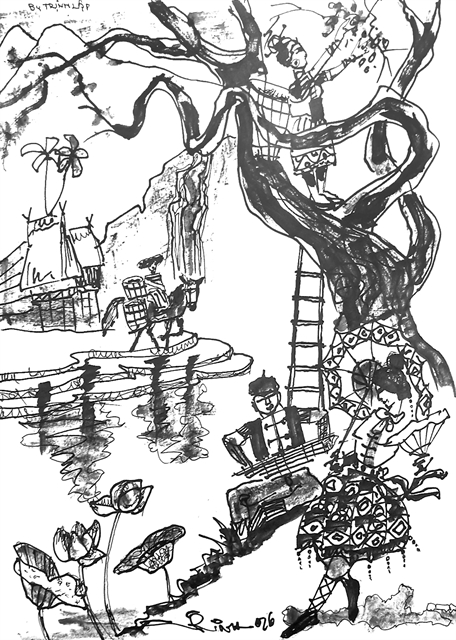

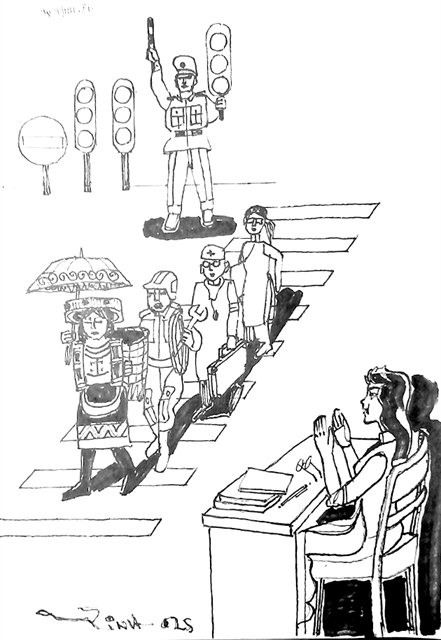

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

Hoàng Thiệu Như

Across the world, in classrooms tucked between mountain ranges or nestled in the heart of bustling cities, children are learning through imagination, laughter, role-play, and questions.

There isn’t always a whiteboard or a textbook. Sometimes all it takes is an old scarf turned superhero cape, or an adventure dreamed up on the spot. In places like these, learning doesn’t begin with tests or grades – it begins with play, where children are free to explore the world in their own way.

That said, educators and researchers, according to UNESCO, are coming to the same conclusion: play isn’t just fun – it is fundamental, especially for children growing up in poverty, trauma or systemic neglect.

Yet in many education systems, especially those under strain, play is the first thing cut. That’s a mistake, and a costly one. Children learn best when they’re actively engaged, using their bodies, their voices and their imaginations.

But for many disadvantaged students, school is more about compliance than curiosity. And when play is removed, what’s often lost is the chance to develop cognitively, emotionally and socially.

For over a century, developmental psychologists have emphasised the role of play in learning. Jean Piaget described play as the foundation for how children construct knowledge through experience.

Lev Vygotsky went further, arguing that social play allows children to operate within their “zone of proximal development” – that sweet spot between what they can do alone and what they can do with help.

Maria Montessori built her entire pedagogy on the idea that children, when given freedom in a prepared environment, learn best through self-directed play.

And the Reggio Emilia approach in Italy has long championed the idea that play is a form of inquiry and self-expression.

These are not fringe ideas. They are supported by decades of research in neuroscience, which shows that play activates brain regions responsible for executive function, emotional regulation, memory and motivation. In short, play helps kids become learners who are focused, adaptable and resilient.

And for children who are disadvantaged, living in low-income neighbourhoods, refugee camps or unstable households, play becomes more than a teaching strategy. It becomes a lifeline.

According to UNICEF, play helps reduce toxic stress in young children exposed to adversity and provides a safe outlet for emotional expression and healing.

When a child who has experienced instability can act out a story, solve a puzzle with a friend or lead a pretend expedition, they begin to rebuild agency, joy and confidence. And those are the very ingredients that make formal learning possible in the first place.

Fortunately, around the world, educators are proving that play doesn’t need a flashy classroom or expensive tools.

In Bangladesh, BRAC’s Play Labs provide early learning through storytelling, music and movement in under-resourced communities. These programmes are run by trained local women and have significantly improved school readiness among children in rural areas.

In Kenya, the Kidogo programme supports daycare micro-centres in informal settlements, where caregivers integrate songs, games and storytelling into daily routines.

In India, rural communities have embraced the idea of toy libraries, which offer children access to low-cost, open-ended learning materials that encourage collaboration and creativity.

Even in Việt Nam, where academic pressure is intense, UNICEF has partnered with the Ministry of Education to help teachers in ethnic minority regions incorporate culturally relevant play, like traditional games or folk tales, into preschool classrooms.

These initiatives succeed not because of wealth, but because of mindset. They recognise that children are not blank slates to be filled with facts, but living, breathing learners who think with their hands and dream through make-believe.

And yet, despite the evidence, many schools still resist play. Why? One major reason is cultural perception. In many places, especially where educational systems are under pressure to produce high test scores, play is seen as a luxury – or worse, a distraction.

Teachers, already stretched thin, may not be trained to use play effectively. Classrooms are often overcrowded, and rigid curricula, leave little room for creativity. Parents, too, may view play as frivolous, especially when they want their children to have a chance at academic and economic mobility.

But even in these settings, change is possible. Some educators have learned to weave play into the existing structure – starting the day with a collaborative story circle, using drama to act out a science lesson or turning maths review into a game.

Others have found ways to reclaim recess or designate short periods of unstructured play, knowing that even fifteen minutes of movement and imagination can drastically improve focus and behaviour.

Training programmes, even simple ones delivered over WhatsApp, have helped teachers in rural areas learn how to use play as a strategy to reach students who otherwise might tune out.

When teachers understand the purpose and power of play, they stop seeing it as wasted time and start seeing it as essential preparation.

The bottom line is this: play is not the opposite of learning. It is how learning begins. And for children facing the greatest challenges – poverty, displacement, systemic neglect – play may be the most powerful tool we have. It doesn’t take money to let kids imagine, collaborate, or pretend.

It just takes a little trust in their creativity and a willingness to rethink what education looks like. Because when we let children play, we’re not lowering the bar. We’re lifting them up. VNS