Society

Society

By Lê Việt Dũng

A woman in the Central Highlands province of Gia Lai is preserving the cultural heritage of the Gia Rai ethnic group through community-based tourism.

H'Uyên Niê, deputy chairperson of the Women’s Union in Ia Mơ Nông Commune, Chư Păh District, established a cloth weaving and basketry club in 2019 to combat the decline of traditional crafts threatened by industrial production.

Her initiative focuses on experiment tours where tourists can take part in daily Gia Rai activities such as weaving, basketry, rice pounding and coffee harvesting. They can also enjoy cultural performances, including gong shows and the grave-leaving ritual.

The initiative has created income opportunities for around 150 locals, each earning an additional VNĐ3 million (US$120) monthly, supplementing their primary income from crop farming and livestock breeding.

Hand-loom weaving plays a central role in the initiative. Rơ Châm H'Xuyết, a club member, says that it takes her at least one month to weave a single piece of patterned fabric and about one week to turn it into a traditional outfit, which can be sold for approximately VNĐ2.2 million ($88).

|

| Gia Rai women weaving the traditional fabric on handlooms. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

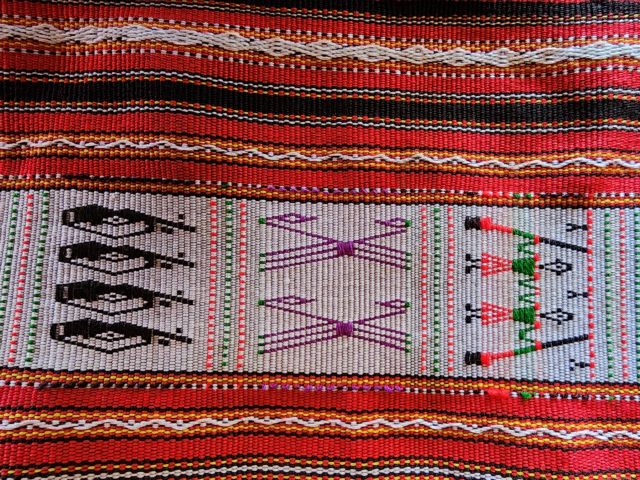

She says that Gia Rai weavers use cotton dyed with natural pigments derived from local plants with indigo for black, turmeric for yellow and tơ-nưng for red.

The fabric patterns often include traditional motifs, such as trees, human figures and chickens.

|

| A piece of fabric with patterns of people pounding rice — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

She also says that pattern weaving is significantly more challenging than embroidery, as it requires weavers to pre-arrange the coloured threads on the loom and use their imagination to form patterns.

Another club member, Rơ Châm Hết, tells how his income improved significantly by selling bamboo backpacks, or gùi, to tourists.

|

| A piece of fabric with human figure patterns— VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

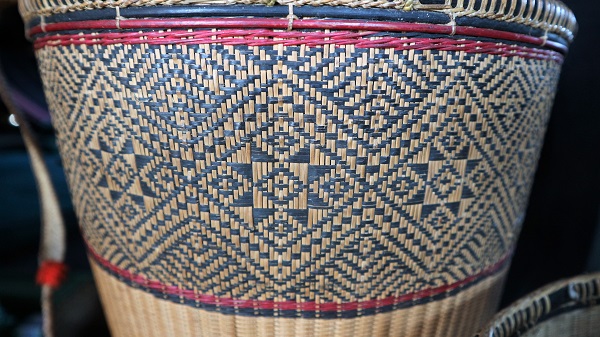

The artisan backpacks come in three types, open-weave for carrying firewood or vegetables, tightly woven for rice or maize, and flat-shaped for hunting supplies.

Basket-making is labour-intensive and involves multiple stages. First, he goes to the forest to pick high-quality bamboo, which he splits into thin strips. These strips are soaked in water, dried and then woven together with rattan to reinforce the base, mouth and straps.

|

| A Gia Rai man weaves a backpack. VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

Each bamboo backpack takes him about two weeks to complete and sells for around VNĐ500,000 ($20).

"Bamboo backpack are durable and entirely handcrafted from natural materials, making them highly popular with tourists," says Hết.

He also says the most challenging backpacks to make are those with intricate patterns, requiring high skills to arrange red strips, stained with a colour made from forest seeds, and black strips, created by smoking bamboo over a fire, in complex configurations.

|

| A bamboo backpack showing beautiful patterns. — Photo baodantoc.kontum.gov.vn |

The tours also include visits to Gia Rai cemeteries, where tourists learn about the community's spiritual practices.

According to Niê, the Gia Rai believe that after death, the soul lingers in the earthly world until the grave-leaving ritual is performed. During this time, family members regularly bring food and other offerings to the grave to "support the soul".

Grave-leaving ritual serves as a transition, allowing the soul to depart for the afterlife and sever ties with the mortal world. The three-day ritual involves family members presenting valuable items at the grave and decorating it with wooden statues, which symbolise love and protection.

|

| H'Uyên Niê (right) explains the meaning of each statue at a grave to a group of tourists. VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

Participants, meanwhile, smear mud on themselves to impersonate Bram (mud spirits) to guide the soul to the other world.

"The statues placed around the grave express the family’s affection for the deceased and serve to protect the site from malevolent spirits," Niê says.

|

| Three children smear mud on their bodies to disguise themselves as mud spirits during the grave-leaving ritual. VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

On the final night, the ritual concludes with a farewell procession that includes a gong performances, puppet shows and traditional dances around the grave.

"I’ve never seen a cemetery like this before, it’s truly unique," says Pranav Seth, an Indian tourist. "I was captivated by the culture, the clothing and how they bury their tribes."

Gong performances are also a highlight of the tours. A set of 13 to 16 gongs is played differently depending on the occasion, such as the harvest festival or funeral ritual.

|

| A group of people perform gong music around a campfire. VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

"Gongs symbolise power, wealth and a connection between humans and the divine," Niê explains, adding that local authorities are organising workshops for the younger generation to preserve this cultural heritage.

The community-based tourism programme in Ia Mơ Nông attracts several thousand visitors annually, 40 per cent of whom are foreigners, significantly boosting local incomes and ensuring the survival of Gia Rai traditions. VNS

|

| Three children catch fish in a lake near their village. VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

.jpg)