Society

Society

Nhật Hồng

HÀ NỘI — When Đinh Thị Tâm Như set her mind on going to her idol’s concert in Bangkok, Thailand, she woke up early for breakfast, offered incense to her ancestors’ altar for blessing and was ready to enter an online ticket ‘war’ that lasted six hours straight.

“I told myself I would only go once to see what the concert was actually like, but I went twice already – and there is no sign I would stop,” a laughing Như said.

|

| Như travels to Bangkok for her idol Jay Chou's concert in December 2023. — Photo courtesy of Đinh Thị Tâm Như |

Talkative and energetic, she has always loved to be out and about – “My grandma used to say she never saw my face at home,” Như said.

When she is not busy planning her next trip, she can be found translating a book using her self-taught Chinese or working on an illustration as part of her freelance work.

Như’s life appears not much different than that of other young women in their mid-20s, but it is the result of her relentless efforts to overcome life challenges as someone born with HIV – even if she is not fully aware of how much strength it takes.

“A friend once asked me how I managed to overcome it all. To be honest, I don’t know the answer either,” she told Việt Nam News.

Stigma and discrimination have been commonplace for people living with HIV, especially during the height of the epidemic in Việt Nam in the early 2000s.

For Như, this means she was not admitted to the kindergarten near her home due to objections from the school board and the other children’s parents.

When it was time for her to attend first grade, her family had to knock on the doors of three different elementary schools in their area before one of them accepted her. But even then, she was not officially included in the school database and was arranged a separate seat from the rest of her class.

“I got ‘outed’ when I was in secondary school. One of my schoolmates knew about my status through their parents, then told everybody at school. I got bullied after that,” said Như.

|

| Như (first row, third from left) at a capacity training session for young leaders of the Vietnam Network of People living with HIV (VNP+). — Photo courtesy of Đinh Thị Tâm Như |

Today Như has maintained the Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) status for over a decade since she was a teenager, and is an active member in the community of people living with HIV in Việt Nam.

The U=U status means that an HIV-positive person who achieves an undetectable viral load – through consistent antiretroviral treatment and monitoring – cannot transmit the virus to their sexual partner.

Understanding U=U

According to the Centre for Supporting Community Development Initiatives (SCDI), Việt Nam has seen progress in reducing stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV, thanks to the collective efforts of multiple stakeholders.

These include policymakers who put forward regulations that ensure the privacy of people living with HIV, the media who convey objective, accurate stories of this community and especially peer support groups, who are working to increase access to testing and treatment services.

However, discrimination still exists in more subtle and complex forms that cannot be addressed solely through legislation, such as unfavourable attitudes or implicit bias during recruitment towards people living with HIV, said SCDI’s Community Support Programme Manager Nguyễn Thị Kim Dung.

“The message of U=U is one of the most important factors in reducing stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV, changing public perceptions and helping to alleviate fear and prejudice toward those living with HIV,” she said.

“Access to U=U can help facilitate support, care and treatment for people living with HIV when they understand that early, effective and consistent treatment enables them to live long, healthy lives, to have children and not worry about transmission.”

Data from Việt Nam’s most recent Stigma Index regarding people living with HIV, released in 2021, also show that internalised stigma is common among this community.

Internalised stigma, also referred to as 'felt' stigma or 'self-stigmatisation', is used to describe the way a person living with HIV feels about themselves, specifically if they feel a sense of shame about being HIV-positive.

Of the 1,623 study participants across seven cities and provinces, 88 per cent responded that they find it difficult to tell people that they are HIV positive and 86 per cent hide their HIV status from others.

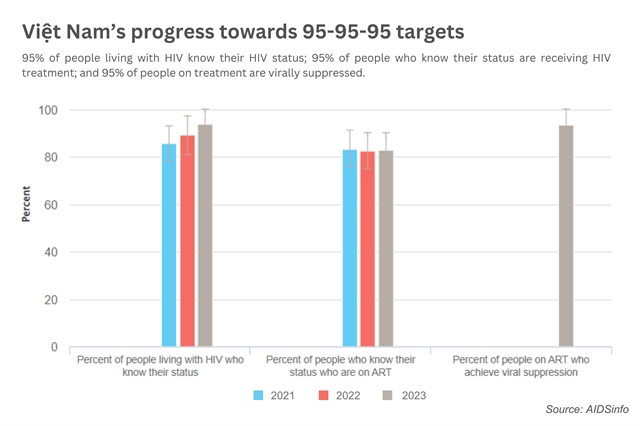

Stigma and discrimination are viewed as one of the key reasons behind the considerable gap between the number of people living with HIV who know their status (94 per cent, per 2023 statistics) and those who are on antiretroviral therapy (83 per cent) in Việt Nam.

|

| The 95-95-95 targets in global HIV response are stated in the Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Ending Inequalities and Getting on Track to End AIDS by 2030, which was adopted by United Nations' member states on June 9, 2021. — VNS Graphic |

Beginning antiretroviral therapy (ART) means people who acquired HIV have to go to a medical facility, to see their doctor and nurse, and other people visiting those facilities, said UNAIDS Việt Nam director Raman Hailevich.

“Because of the fear of stigma and discrimination, they might prefer not to do that, or delay doing that, because someone may see them there,” he explained, noting that there are also concerns regarding the confidentiality of their medical information.

Fair and equitable access to HIV prevention and treatment services is also the theme of this year’s National Action Month on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control (November 10 – December 10), aiming to ensure that everyone can receive the health services they need without discrimination.

This is Việt Nam’s response to the 2024 World AIDS Day’s theme of 'Take the Rights Path', underscoring the human rights of people living with or affected by HIV, especially regarding their healthcare – which is seen as a critical approach to reaching the goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

U=U can mean healthy children

Đinh Hoàng Châu Bảo, an active advocate for people living with HIV in the southern Bến Tre Province for the past two decades, is an inspiring example.

She was diagnosed with HIV 25 years ago and has been on ART since 2010.

When HIV viral load testing became available at Phạm Ngọc Thạch Hospital in HCM City in 2015, she was confirmed to achieve an undetectable level and has maintained this status since.

|

| Đinh Hoàng Châu Bảo (centre) at an annual meeting of Vietnam Vulnerable Communities Support Platform (VCSPA), of which she is also part of the governing board. — Photo courtesy of VCSPA |

Bảo’s two children, whom she had with her first and second husband – both HIV-positive – did not acquire HIV.

“My first child could be seen as a fortunate case. But with my second child, I was sort of an ‘experiment’ for my community,” Bảo said, explaining that: “It was a time of transition from crisis to acceptance, when couples in the community came to term with living with HIV and maintain treatment together.”

As their health conditions stabilised, then came the desire for children.

The year after she delivered her second child, nearly ten other children were born in her local group of people living with HIV, all HIV-negative, healthy and well. “Some of them are entering secondary school now,” said Bảo.

U=U means a dedicated life

In 2018, Bảo was recognised by the national Red Ribbon Awards for her commitment to helping expecting mothers in her community to strictly follow their HIV treatment, take preventive measures against perinatal transmission and deliver safe births.

Together with fellow members of her local community, she also formed Bến Tre’s Liên minh Nhân Ái (League of Kindness), which gathers seven peer support groups for those at risk or affected by HIV by reaching out and connecting them to healthcare services as fast as possible, providing consultancy, and assisting in administrative procedures and even employment.

Many people living with HIV in Bến Tre have been able to secure their livelihoods by working at Bảo’s spice and coconut production facilities, but seeking job opportunities for people from the community is always on her mind.

A stable job and income are a fundamental factor for people living with HIV, especially people who used drugs or were incarcerated, to improve their quality of life, she said.

|

| Bảo also runs an annual support programme for children and families affected by HIV in Bến Tre Province to help them continue their education. —Photo courtesy of Đinh Hoàng Châu Bảo |

“My wish is that people living with HIV do not die because of HIV – to me, that feels as though they die unjustly,” said Bảo. “Therefore, I continue to do all that I can to reduce the stigma and use my voice whenever I have the chance.

“When people have correct and sufficient knowledge, they are no longer afraid nor discriminating, then people living with HIV can lead an easier life, and our society becomes more inclusive.”

As for Như, last year, she successfully pitched her idea for a micro grant from Love Positive Women, a project encouraging acts of love and caring for women among people living with HIV, supported by the International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW).

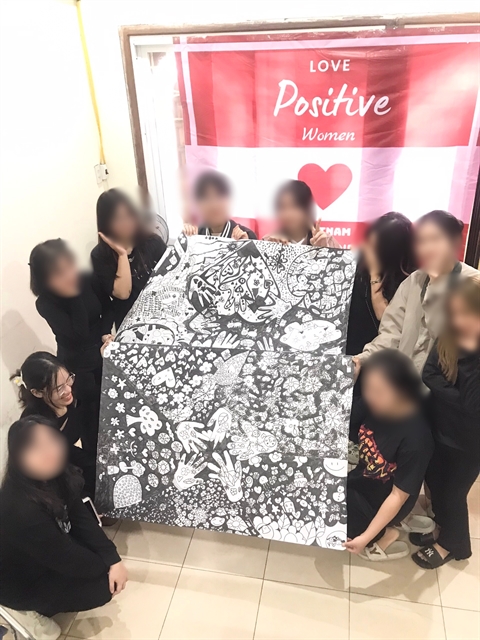

|

| Như and the young women living with HIV in Hải Phòng with the artwork they created together as part of the workshop held in early February this year. — Photo courtesy of Đinh Thị Tâm Như |

Being the only submission from Asia selected in the 2023 funding round, Như’s workshop Art of Connecting was the first activity for young women living with HIV in her hometown – the northern Hải Phòng City – to engage, communicate and interact in activities designed specifically for them.

“Everyone also said that this was the first time they worked in a team and the first time they felt listened to and respected in a group,” Như said. She is now gearing up for this year’s funding application.

Even with the ups and downs of her childhood, Như believes her story extends far beyond what she experienced in the past.

Her focus now is on the future – her health, her job, and her aspirations to support the community. — VNS

*This story is produced with the support of UNAIDS Southeast Asia Against Stigma Fellowship