Expat Corner

Expat Corner

John Balaban’s warm smile, friendly manner, sincerity and especially his profound knowledge of Vietnamese folk songs and literature has made him a close friend to many Vietnamese scholars.

|

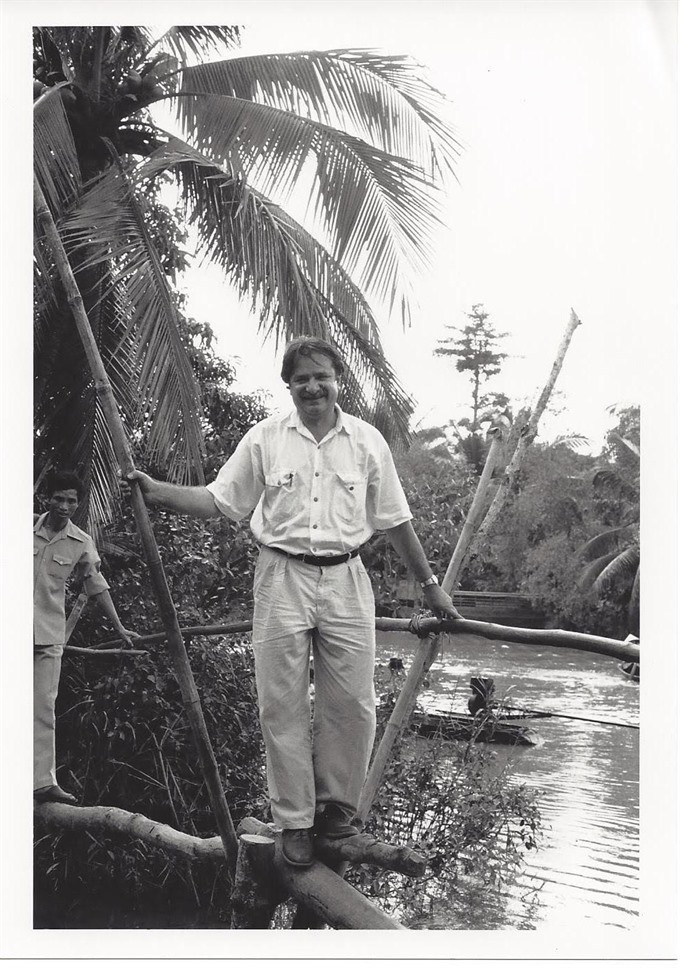

| Delta detour: John Balaban on a trip to Cần Thơ in 1989 to visit a family of one of the children he helped treated in the US for her war injuries. Photo courtesy of John Balaban |

By Lê Hương & Hồng Vân

Coming to Việt Nam during the American war as a voluntary teacher of English at Cần Thơ University, a 24-year-old American man did not know he would find the inspiration for his life’s work.

Over the past half century, over dozens of visits to Việt Nam, John Balaban’s warm smile, friendly manner, sincerity and especially his profound knowledge of Vietnamese folk songs and literature has made him a close friend to many Vietnamese scholars.

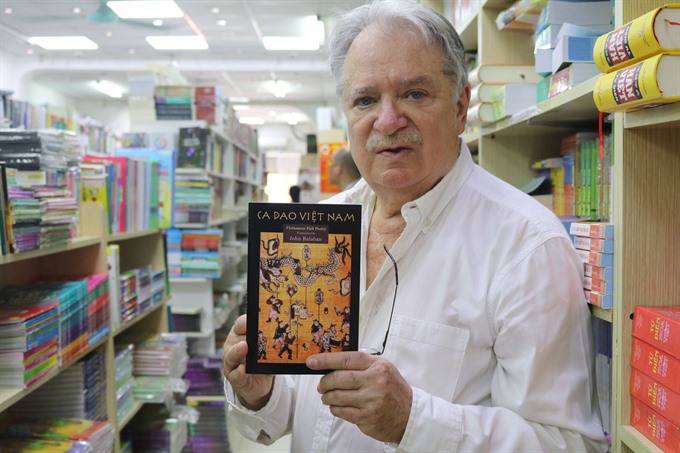

Balaban is the author of 12 books of poetry and prose, including four volumes which together have won The Academy of American Poets’ Lamont prize, a National Poetry Series Selection and two nominations for the National Book Award (one for After Our War, published in 1974, and the other for Locusts at the Edge of Summer, published in 1998).

He has also been known as a researcher of Vietnamese literature and the founder of the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, which helps popularise the ancient ideographic vernacular script of the Vietnamese language over the internet.

He first came to Việt Nam with the International Volunteer Services in 1967, where he taught at what was then called Cần Thơ University until it was bombed during the Tết Offensive in 1968.

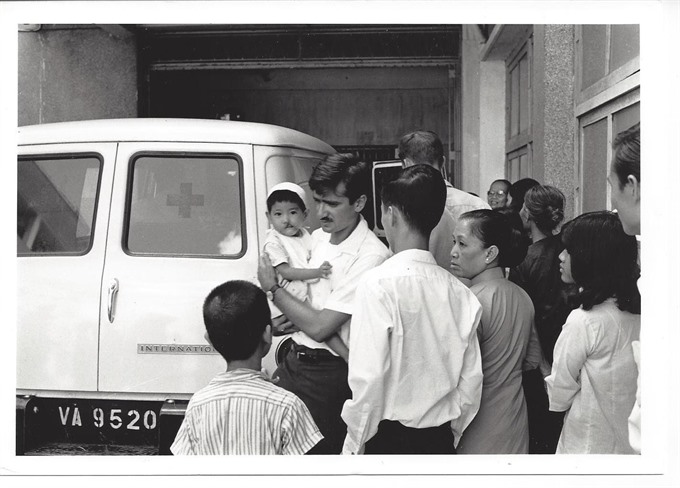

He was wounded in the shoulder by shrapnel and evacuated; after his recovery, he worked for the Committee of Responsibility to Save War-burned and War-injured Children.

“Sometimes I travelled along the rivers, along the Mekong, I could hear people singing folk songs (ca dao in Vietnamese), and I didn’t know what it was,” he told Việt Nam News. “I visited families, I would hear people singing all the time, everywhere, in the orchards, behind the house. I got curious and I decided to collect them on tapes.”

He returned to the US in 1969 but again found himself in war-torn Việt Nam in 1971, to wander around the countryside with a recorder over nine months to record folk songs.

“The singing tradition is almost thousands of years old—everybody can sing, from little children to men and women.”

“The war was going on when I collected ca dao. You can hear rifle and mortar fire in the background on some of them. And so it wasn’t safe for me to go everywhere I wanted, deep into the countryside where ca dao lives. Otherwise, I had nothing but help from the Vietnamese I met, recorded, and spoke to,” he said.

To him, the beauty of the singing and the content of the songs reflect a cosmology that is itself old and powerfully informative.

In 1973-74, he joined Prof Trần Văn Khê and film maker David Grubin to produce a short film titled Ca Dao: The Folk Poetry of Vietnam, which was then screened at many universities in the US.

His first book of translation, Vietnamese Ca Dao, was published in 1980 by the Unicorn Press. The Copper Canyon Press reprinted it with the Vietnamese originals and more authorative introduction. In 1984, the Pennsylvania State University re-distributed his short film Ca dao: The Folk Poetry of Vietnam.

“My one contribution to knowledge about ca dao may be my research into its music; my other contribution -- besides collecting hundreds of the songs on tape -- was in finding a way to date the tradition through lexico-statistics dating,” he commented.

|

| Humanitarian: In a photo taken in 1969, Balaban embraces a little girl who was being sent to the US for medical care. Courtesy Photo of John Balaban |

|

| Bookworm: Prof Balaban poses with a copy of his book on Vietnamese ca dao that he finds at a bookstore in Hà Nội. VNS Photo Hồng Vân |

Ca dao led him to Hồ Xuân Hương, a preeminent18th-century poet of Việt Nam. Some Vietnamese scholars suggested him to do research on Hồ Xuân Hương, whose vocabulary was close to that of ca dao, although of course it is still imbued with the thơ đường luật (Vietnamese variant of Chinese Tang poetry) tradition.

“At first, I did not even understand that she wrote in chữ nôm, or what that is. To understand her, I needed to be educated once again by learned Vietnamese.”

His book of translations of Hồ Xuân Hương’s works called Spring Essence: The Poetry of Hồ Xuân Hương garnered great interest when it came out in the year 2000.

Though he made the translations from modern Vietnamese language as well as the French translation by Maurice Durand and with help from Vietnamese Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng and scholar Đào Thái Tôn, her work showed him the possibility that there was much more literature written in nôm that deserved to be brought to world attention. With the IT experts James Đỗ Bá Phước, Ngô Thanh Nhàn and later Ngô Trung Việt, he started the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation to open worldwide access to all the poetry, history, religion medicine, royal decrees written in nôm, which can be read by fewer than 100 scholars throughout the world.

Since its establishment in 2009, the foundation has praised nine Vietnamese scholars and one Japanese scholar for their efforts in preserving the ancient writing system of Việt Nam.

Balaban said he remembered three words that a monk gave him long time ago: Thiên, Địa, Nhân (Heaven, Land, People) and he used those words to describe Việt Nam and Vietnamese culture, which is a general harmony between the three factors of the universe.

"I find him a person with special love for Việt Nam from a very young age," said Ngô Trung Việt, a retiree from the Việt Nam Science & Technology Institute and a close friend of Prof Balaban since 1999. "His translations of Vietnamese folk songs and Hồ Xuân Hương’s poems have been highly appreciated by both international and Vietnamese scholars.

“He is also an intellectual with good capability to connect experts from various fields to work for a purpose, like for the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation," he added. "He has really done a lot for Vietnamese literature."

Mentioning the changes of Việt Nam over the time, Balaban noted that the country’s colour palette seemed to have shifted from the grey necessities of nation at war to the vibrant hues of a fast-evolving and diverse country.

At 74, Balaban said he was afraid that this would be his final visit to Việt Nam.

"I just retired from teaching as a university professor. I am working on a new book of poetry, my own,” he said.

Looking at his eyes and listening to him reciting Vietnamese folk songs, one could not help believing that he will keep thinking of Việt Nam until his last gasps. — VNS