|

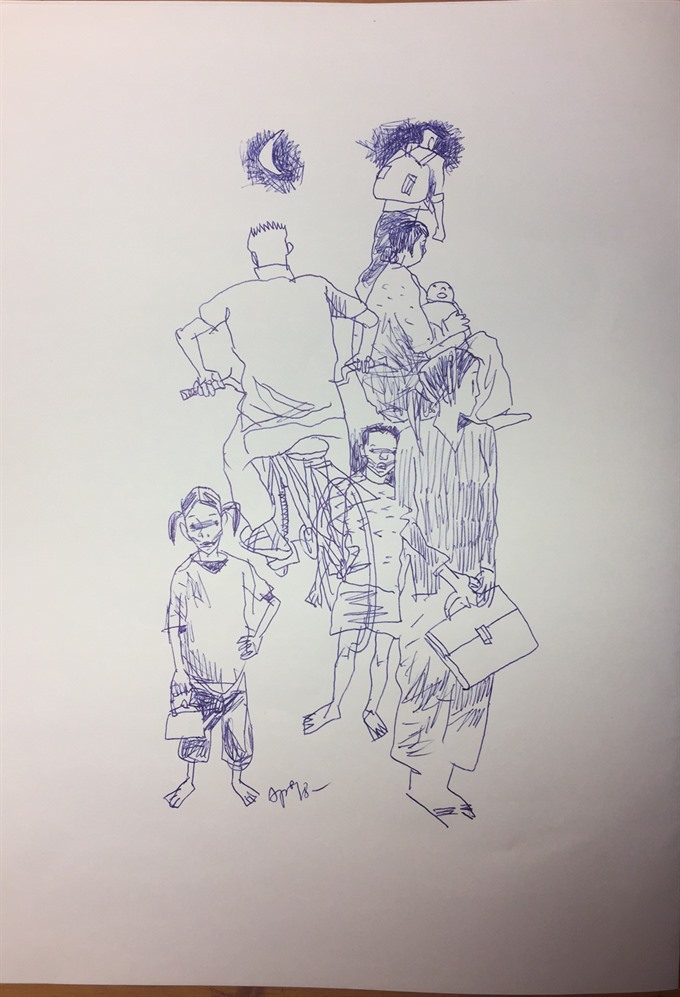

| Illustration by Đào Quốc Huy |

by Phan Mai Hương

The hot and dry westerly wind howled and swirled, whipping up the dull red soil into the sky then dumping it down. Two uneven rows of houses with dusty brown-and-grey palm thatch roofs lining the road choked in the pinky brown dust. In all directions mountains shot up, bristling and tottering as if they would collapse after a slight collision. At the T-junction, there was a banyan tree with ancient roots and a canopy spread wide like a huge umbrella, shading the ground. Around the foot of the tree, children and a few adults were selling peeled and separated pomelo pulps which were withering under the sun, and sugarcane fruits and pineapples which were cut and packaged in nylon bags. Cucumbers, boiled corncobs and sweet potatoes were in baskets, and green tea stored in aluminum pots were offered to passers-by and passengers on buses that stopped for a break. The plastic cups dangling upside down over the spouts of the pots seemed ready to fly off every time the kids took to their heels to entice customers. Receiving a cup of tea from a skinny girl with hard dark skin, a face full of freckles and a nimble and sly look, Thi dispiritedly looked at the sickening sunlight forming colourful circles in the air when she was told that to reach her new school, she would have to travel another two kilometres. A bicycle screeched to a halt right in front of her. The chain was broken, linked to one pedal on one side and a very sharp-pointed crank arm on the other.

“You seem to be going to the high school, teacher?” Thi looked up at the person who asked the question and saw a pair of warm brown eyes under a head of hair which was ruffled like a sparrow’s nest in a storm scanning her from head to toe. Before she had time to answer, a hand lifted up her suitcase and put it on the backseat.

“I’m on my way back to school too so I’ll carry it for you, teacher!” No sooner did Thi say yes and was about to ask who he was than the bicycle shot away, leaving behind a streak of red dust. His slim, curvy back floated forwards in the dazzling sunlight. In the middle of a vast pasture covered with lumpy rocks of all sizes, a few rows of thatch-roofed houses stood alone, making the school where Thi was to teach. Another separate line of houses with arch roofs lying flat on the ground like turtles with broken legs was the school’s board room and teacher’s dormitory. Outside the bamboo picket fence lay an uncultivated field. Later, after staying here for a long time, Thi would come to know that the school was destroyed and had to be rebuilt several times every year because of tornadoes. Her new colleagues gathered to question her vivaciously. Only when they asked where her luggage was did Thi remember it. Right then, the ruffled head of hair appeared out of the blue from behind the bamboo fence gate with a bright smile and an explanation:

“I had to drop by a student’s house to persuade her parents to let her continue to go to school, was pressed to stay and eat with them, could only leave after much protest.”

It was Hoàng Hữu, a geography teacher who was two years older than Thi. Upon hearing his story, the others rolled around with laughter. The school’s president named Luân told Thi: “You were too gullible. You were lucky to have met a good person.”

Only after Thi had left this place which had too much hot and dry wind, frost and rocky mountains but too little water did she feel the truth of his words.

** *

Thủy’s house, a wooden one with a brownish roof, would be a dream compared to the room Thi was living in. Thủy was thirty-two years old. Though she taught history, there was no sight of any history book in her house. All knowledge was swept away under a mess of her concerns. Day and night she took care of three daughters and two parents-in-law who were almost eighty, did gardening work, went to the market, worried herself about birth control, about her driver husband who might try to “secure a son” on the road, which made her face and figure - which might have been pretty in the past - shrivel like a salted apricot dried under the sun. All three of her daughters looked dirty after crawling about in the yard or creeping into bushes all day. Only their eyes remained clean, glistening and crystal clear. Children had countless pleasures which adults could hardly understand. Was this Thi’s future? Was Thi happy or sad? She felt happy because she had volunteered to come here to teach. Thi’s father hadn’t helped her find employment in her home city. His friend, a senior education official, suggested that since she was still young she should teach first in the countryside for a few years to gain experience.

Thi was still daydreaming when Hữu showed up and asked her to go to the market with him. Thi shook her head saying she was busy. Instantly she remembered the day of the market fair when people flocked to town, when the tow of them drew close to a boy carrying a bright green bamboo cage which was holding what looked exactly like a small python. Hữu merrily said, “With just one month’s salary, we can buy the python to raise for some time then kill to make glue. Python glue is incredible and may cure your mother’s backache.” The two labouriously carried the ‘python’ home. Putting the cage down, Thi gingerly opened the lid. The ‘python’ sprang up, puffed, bared a red patch around its neck, flicked its forked tongue. As swift as a deer, Hữu slammed the lid shut. The cage was immediately flung away into the bush outside the fence towards the vast field.

The afternoon darkened. The flaming sun rolled up and descended behind the purple-blue mountains. Dew sneaked round, spinning a blurring web over every crook and corner, freezing the air into a biting cold. Leaves had been shrunken by too much sunlight and frost. The sky looked opaque due to the light radiating from a half-moon. Walking past Thi’s door towards the well with a basket of vegetables in her hand, Nhã smiled at Thi then tilted her chin up towards her room, signaling that Vũ had arrived. Nhã was a Hanoian, who had arrived at the school a month after Thi, was pretty enough, considered teaching secondary to her "primary profession" of trading pharmaceutical products, and had a boyfriend named Vũ. Nhã said Vũ’s family had the biggest shop in the whole street, his mother was an experienced businesswoman and took charge in the house, and his younger sister inherited all of her mother’s good traits. Nhã laughed and said, “I’ll have two mothers-in-law by and by.” Vũ was extremely jealous. Whenever Nhã stayed at school, Vũ would travel 100km only to quarrel with her without talking to anybody else. The sound of them fighting mixed with the hoarfrost, alternating between loudness and quietness, echoing along the dorm. Being tall and handsome like an actor, Vũ nonetheless felt jealous, though nobody knew of whom. No man here dared approach Nhã. Every man here was unfamiliar with Vũ’s type. Vũ made people feel exhausted. Was love good or bad? Nhã said Vũ’s family had spent lots of money to bribe some powerful official to transfer her back to Ha Noi, but she seemed unwilling.

The moon sprinkled its dusty golden light, giving the lifeless dried-up trees a fresher look. Sitting on a sedge mat in the yard, Thi and Nhã turned towards the room in which Đô, who came from Ba Vì, was living. Thi was a little amused by the contrast between the name which meant big and muscular and Đô’s stunted physique. Though he taught Russian, Đô habitually mispronounced the language. Wrestling the bicycle down the yard, Đô patched up a tube in a creative way: plaiting rags into a bun, coiling it up tightly, tying it to the rest of the tube and stuffing everything inside the tire. The two women giggled, pitying the rickety bike which would have to roll over 30km of road to a higher region where Đô’s tall, broad-shouldered, manly girlfriend was teaching at an elementary school. Đô would come home unscathed, carrying along dried bamboo shoots, honey, snakes, turtles and geckoes which his girlfriend had amassed in a week in order to sell for profits which could exceed several months’ salary. Thi found Đô’s love story kind of cool, tinted with familial care. Thi remembered when she was young her parents only discussed money and debts at night when their children had gone to bed, but Thi was still awake so she eavesdropped on them. Knowing her family’s difficulties, Thi always took great care of the garden so that it yielded many vegetables for her mother to sell at the market. Mai swooped down on the sedge mat and told her stories. In her hometown where rocky mountains slept eternally amid white clouds, girls never went to college, shamans made love charms and couples would stick to each other like a pair of glutinous rice cakes made for the Lunar New Year, not even death could do them part. Mai recalled when she was small, she had witnessed a wife who didn’t eat or drink for seven days and fell dead upon her husband’s grave, all because of a love charm. Love charms only worked for three months, and afterwards had to be replaced by new ones. Making love charms was a difficult profession. The shamans only taught it to generous, virtuous people, at night, and for 100 consecutive nights. A late sleep was broken by the mystery of the love charms in Mai’s story. Near dawn Thi was waken by the repetitive clacking sound of the opening of the door next to hers. While Thi was falling back to sleep, a thought kept hovering in her mind: Was money or love more important? Thi saw the light of the oil lamp from Hữu’s room floating away towards the rocky field, gliding after a wriggling snake tail. She saw her mother turning to walk away and herself screaming and running after her. Thi startled up out of sleep, realising it was just another dream. She thought about her father’s words: “Now that you are a government employee, you must take care of your career on your own.” Everything seemed to flicker in bewilderment in the biting cold frost.

***

Thi gathered a bundle of freshly split firewood and poured a little oil on top. No sooner did she drop a match than the fire flared up, exuding the acrid smell of burning oil. Dreaming about a cool breeze, Thi sang quietly, “The afternoon is serene, the wind rustles gently.” Suddenly she heard a thudding sound on the wall: “Thi, eat fast and go out with me.” “What a liar,” Thi retorted. “I’ll thrash you. Everybody knows you’re going down to your girlfriend’s house. Does she come home midweek too?” Thi heard no answer but the crispy crackling of the bike rolling in the yard. Tín, chemistry teacher and secretary of the teachers’ youth union, was meticulous by profession. His Chinese bicycle was always polished and fully pumped. If a tube was punctured, he would haul the bike to the yard and go over every old and new patch. Though the patches overlapped one another, the bike could still carry his sweetheart exceptionally well. After eating dinner, Thi checked the jackfruits her students had brought as presents to see whether any of them had ripened. She spread a sedge mat on the yard and called Nhã. Thi and Nhã loved jackfruits, but in such scorching heat they had had to wait until midnight to satisfy their craving. As for Mai and Hữu, they were indifferent to jackfruits so didn’t participate. Looking at the yellow colour of the jackfruit pulps blending with the golden moonlight, Mai lamented, “It’ll be very hot tomorrow.” After eating the jackfruits Thi went back to her room. She felt very drowsy but couldn’t sleep because of the terrible heat. The diesel oil lamp emitting smoke on her desk only made the air hotter. As Thi was dozing off, she was startled by the crackling of the bike cassette rolling and the clacking of the door opening. Tín cheerfully teased: “Thi, let’s go to the youth union’s meeting.” If only she could get up and slap him on the mouth. Thi lay still, pretending to be sleeping. Yet Tín went on croaking: “Don’t pretend. I know your trick. You can’t sleep without breathing like a corpse like that.” The wall which was supposed to separate one room from another turned out to be useless. Thi heard Tín clack open the door again. “Sleep, where are you?” Thi moaned. “I have five classes tomorrow.” Sleep came fitfully amid the clacking of the door. Thi’s arm felt numb after incessantly fanning herself with a bamboo fan, yet the heat only seemed to thicken. Of all the dorm rooms, only Mai’s door remained open. Unable to coax her eyes closed, Thi went over and looked inside. She was surprised to find Mai assuming an odd posture, crawling with her butt up on a small plank bed writing something amid a disorderly bunch of old smeared yellow newspaper issues. It turned out she was writing a letter of contrition about her pregnancy which had just been discovered by the labour union. She tried to smile at Thi but her eyes brimmed with tears. The Europeans who discovered America might not have been as stunned as Thi now. “Who is the baby’s father?” Thi asked. Mai suppressed a sigh and said she would never tell. She would give birth. She thought it would be a boy. “Will you help me, Thi?” Mai asked. “Please write the letter of contrition for me.”It was a most difficult essay question.” So who is going to read your letter?” Thi asked. “The managing board, the labour union, the party cell, though not the youth union whose members were away,” Mai replied. Then she added, “I was just informed of the meeting this afternoon.” All of a sudden Thi remembered that Hữu had left to visit his hometown and thought this was a strange meeting for censuring a teacher, because only officials would attend. “So what do you feel contrite for?” Thi continued. “Are you going to say that love is wrong? The new law about marriage and family does recognize children born out of wedlock, doesn’t it,” she said. “Yes I know,” Mai said and pushed a Women’s Newspaper copy towards Thi. “Ah! Why don’t I write a report instead?” Mai said. Thi asked: “So what are you going to report? Are you going to report how many times you slept with that man, and in what manner you did so to get pregnant?” Thi’s question stupefied Mai. “Yeah isn’t that right?” Mai said. “I can’t write like that, can I?” Thi said: “You just go and ask the people who are going to censure you to write for you. As for me, I have no idea what those things mean.”

***

In the end no meeting was held because Mai didn’t write anything. Yet people were worried this kind of incident would happen again. So Mai’s affair was handled quickly, after the officials made Mai promise that she wouldn’t make the same mistake twice, because having one fatherless baby was much more than enough. Thi thought it was difficult to be an official, because they must have such far sight. Thi knew Mai would still teach as normal because she was the only maths teacher in the whole school. If she was suspended, the school would collapse. Yet if Thi stayed here for a long time, another five or ten years, who knew if she wouldn’t follow in Mai’s footsteps? Thi felt the road leading her back to the city was so long. Thi went over to Thủy’s well, dropped the rope of the bucket in its full length, but the bucket kept clattering as it touched the rocks at the bottom without scooping up any water. Thủy’s husband who was standing in front of the pigsty called out: “You have to wait a bit until the water comes out.” After washing her rice, Thi went down to the thatch tent which was enclosed into a tiny kitchen for the teachers, piled two wooden chairs upon each other, pulled both legs up and squatted on top. She had to take this posture to avoid ticks, those blackish sesame-sized arachnids jumped and crackled like black magic. Wherever they touched, the skin would swell and fester into a red and itchy lump which would have to be scratched until it bled. Thi was horrified by this blood-sucking species which covered the kitchen ground like black sesame sprinkled on dry pancakes.Ticks and chicken poop loved each other though, and right behind the kitchen was Mai’s hen-coop. Back at home, around dusk, Thi was most afraid of being ordered by her mother to go close the hen-coop. No matter how quickly she bolted the door, a few ticks would manage to jump onto her. Yet this chore also made her pity her mother who out of worry would creep inside the coop to count the fowls to make sure they had all come home to roost, or to pull out those cold dead corpses infected with a disease.

***

It was two weeks before a new school year. The school yard was empty and quiet. Grass grew thickly, purple flowering bushes crawled freely everywhere. A cow and her calf chewed grass in front of the board room. A bag of withered green papayas which might have come from Mai’s lover was hung on the front of her door. Mai briefed Thi on the latest school news. The most surprising item was Tín’s transfer back to his hometown in Vân Đình. His foster father was the vice chairman of his home district and had managed to transfer him. All procedures were processed in just a week. This move was unexpected because Tín hadn’t said anything before the vacation. “So is he going to break up with his fiancé?” Mai didn’t answer Thi’s question and looked away. Yet Thi had caught her eyes reddening and tearing up.

Another earthshaking piece of news: Đô had been killed by the king cobra which he took to Ha Noi to sell. It bit his hand when he was trying to pull it out of the cage. Because of the long distance, only the members of the managing board went to his funeral. So Đô died for a profession which was not his calling. Thi felt both sad and hurt for his fate. Mai said Đô’s girlfriend had cried her eyes out and insisted on mourning like a wife. “She’s loyal,” Mai said. “But we never know, only time will tell. Three years in mourning are a long time, her youth may be wasted,” Mai added. Yet Thi thought everybody had the right to make their own choices. “By the way,” Mai continued hesitantly, “Hữu came back to school once, saying he would travel south.” Thi was silent. So she wouldn’t have another opportunity to drown herself in his warm brown eyes. Thi shuddered upon remembering the three-red-stripe neck of the ‘python’ swelling up and realised she might be the reason Hữu decided to leave.

Mai cheerfully continued: “And here is some good news for you, Thi. Your student Nghĩa has just passed the entrance exam to the University of Education. She said she was most indebted to you, because if you hadn’t urged her mother to let her finish high school, she wouldn’t be here today. You bring honour to our school Thi. This is the first time our school has had a student pass the university entrance exam. Well, Nghĩa still looks dark and scrawny though she’s already a college student. But she studies extremely hard and shows great determination, the determination of a poor fatherless child who has worked to feed herself since she was small.”

Mai went into labour. When Thi and the midwife arrived, the baby had already shown its head. Thi held the baby, and the midwife cut the umbilical cord and removed the placenta. Thi hadn’t expected Mai to risk giving birth at home. Yet Thi knew Mai refused to go to the hospital because she was insecure and afraid of having to hear people gossip. It wasn’t much of an exaggeration to say that in this little rural district, a sneeze would wake up all the inhabitants, let alone a teacher giving birth out of wedlock. Now Mai’s small room resumed its usual quietness, flooded with diapers, drowning in an iffy milky newborn smell and a stinky mother odour. Thi easily detected these scents, because she was getting used to serving mother and child.

The boy was healthy and seemed to foresee his destiny, so he didn’t fret or cry, but fell fast asleep after sucking his mother’s breasts. Because of her meagre diet, Mai didn’t have much milk and had to feed the boy with rice water mixed with sugar. Yet the boy was satisfied, showing no sign of complaint. The only problem was that there was no word from his father who had fled without a trace. The son looked exactly like his father, starting from the toes and fingers, or so his mother Mai said. Thi thought all the sneers and censures deserve to be thrown into the deep stream and flooded away. Mai said she didn’t want to force the issue, love must be voluntary, and she was willing to let the father return to his hometown, though in the future he would have no right to claim the child. Mai also smiled, half jokingly, and said, “If I put a love charm on him, there’s no way he can run away, really!” Thi’s mind was again filled with the clacking sound of the door opening and closing at night that echoed from Tín’s room. Mai bewildered Thi, making her wonder whether love charms really existed. Thi wondered how the father could reject such a cute boy. The afternoon felt disconsolate, turning dark purple at the foot of the mountains. Dew started to pour out. Thi could smell the coolness of the dew permeating the air. Thi thought how bold Mai was, but perhaps Mai had made the right decision.

Nhã went up to the school on her business trip to collect money from customers. Getting wind that Mai had given birth, she visited Mai, bringing chicken eggs, honey and some clothes for the boy. Seeing Thi, Nhã prattled away joyfully. Nhã boasted she had been confirmed of her transfer back to Hà Nội. “I’ll miss this dreary brushwood, especially you, Thi!” she said, “but I may not teach again! I’m getting married, but not to Vũ. Will you come to my wedding, Thi?” Thi heard buzzing in her ears, understanding nothing, burying a sigh in her chest, smiling and congratulating Nhã. Nhã would be happy for sure, because though she was also a literature teacher, Nhã was practical. She didn’t think as much as Thi. Thi remembered Hữu once telling her, you shouldn’t think too much or else even your body will melt into thoughts.

So what was happiness? Was it getting jealous, missing someone, being possessed? Thi didn’t know. Carrying a basin of dirty clothes from Mai and her son to wash, Thi walked past the opening of a cave by the stream and remembered the man who had warm brown eyes, whose ears and arms both trembled uncontrollably and reddened feverishly when he had dared to embrace and kiss her, during break at a work event of the youth union. The sweet kiss made Thi miss Hữu dreadfully, so much so that whenever she thought about him she felt like a stone was choking her chest. If Hữu was here, Thi would throw herself into his arms. Thi missed the brown eyes that sank deep into sadness, throughout the final week, before the summer vacation. Hữu went back to his hometown without saying goodbye to her. Thi returned to school early in part because she wanted to see Hữu, hoping he would understand that her heart was torn in two. One half was for the warm brown eyes and the children running like the wind with their green tea pots. The other was reserved for her beloved city, where her family and childhood friends lived. When she was back home, Thi wanted to return to school, and when she was at school, Thi wanted to go home. So where was Thi’s love charm? To that she had no answer. Thi only knew she had lost the warm brown eyes, dropping them down the deep cold waters.

Translated by Thùy Linh

.jpg)