Inner Sanctum

Inner Sanctum

A team of researchers, including Trần Hậu Yên Thế, Nguyễn Đức Hòa and Hồ Hữu Long, have published a book on the nghê, a sacred animal that guards ancient temples and communal houses. Lê Hương spoke with Trần Hậu Yên Thế, chief editor of the book.

|

| Trần Hậu Yên Thế poses for a photo by an ancient stone nghê. Photos courtesy of Trần Hậu Yên Thế |

A team of researchers, including Trần Hậu Yên Thế, Nguyễn Đức Hòa and Hồ Hữu Long, have published a book on the nghê, a sacred animal that guards temples and communal houses.

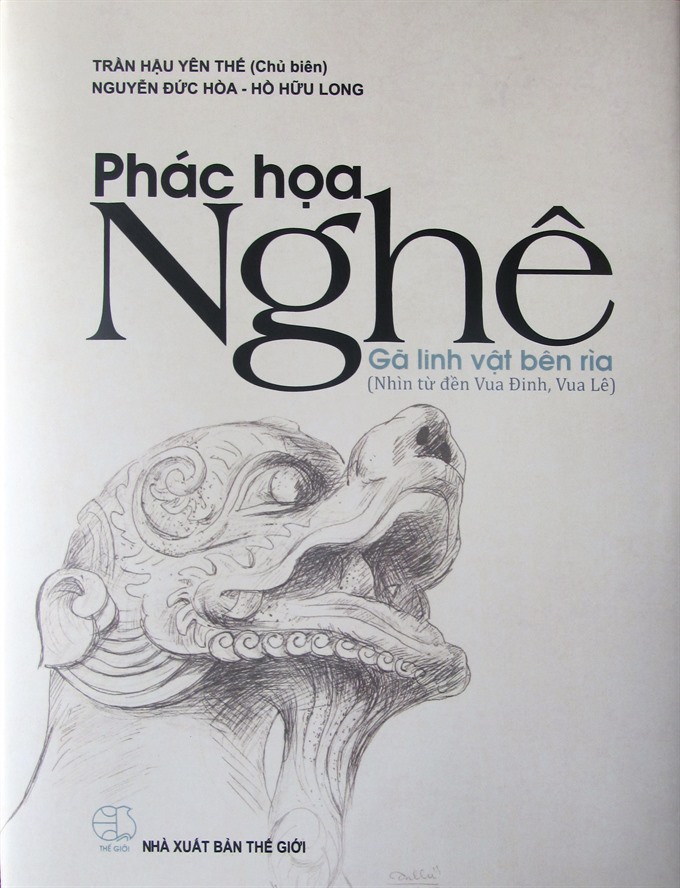

Titled Phác Họa Nghê – Gã Linh Vật Bên Rìa (Sketching Nghê – a Sacred Guardian Animal), the book starts with images of the nghê at temples dedicated to the Đinh (968-980) and Lê (1428-1527) kings in the central province of Thanh Hóa. It then explores the appearance of the animal at holy sites in other regions. The nghê, a mythical creature with a lion’s head, a long tail and a dog-like body, has appeared at temples, pagodas and mausoleums serving ordinary people as well as royal figures.

Lê Hương spoke with Trần Hậu Yên Thế, chief editor of the book.

Inner Sanctum: The book is the result of a 10-year research on the nghê, undertaken by you and your colleagues. Please tell us about the research. Why did you choose this sacred animal? How did you conduct the research?

Work on the book started more than 10 years ago. In 2005, I returned home after a course in Beijing, China. Researcher Lê Văn Thao, head of the Enter Viet Nam Group, and painter Nguyễn Đức Hòa invited me to coordinate with them to write a book on sculptural art in the Đinh and Lê kings’ temples in Thanh Hóa.

I was responsible for studying artworks made of baked clay and stone at these sites. The nghê moved me the most among the works. Two of the seven chapters I wrote were titled Nghê – All Shades and Nghê – From Eyes to Smile, Solemn and Cheerful. These are the two features of the nghê that struck me the first time I researched the animal.

To be honest, though the former citadel Hoa Lư is located fewer than 100km from the capital Hà Nội, I set my feet there for the first time in 2005. The temples of the Đinh and Lê kings are among the largest in the country. I was lucky to be chosen to understand the animal’s story. These are stories of happiness, joy and even sorrow, which have been summarised in stone for hundreds of years. This is a fresh feature I found during my research. In general, in the book, I have pointed out that ancient people carved in the nghê their joys, sorrows and their souls.

Inner Sanctum: What challenges did you face during your research?

First, the primary difficulty in conducting research on ancient fine arts is finance. However, I realised that money is important but not decisive. The decisive factor is the research concept. So, the book on fine arts decoration in the temples of the Đinh and Lê kings was sponsored by the Xuân Trường Company, while the book on the nghê at the two temples was sponsored by the Hà Nội Ceramics Museum.

|

| Cover of the newly published book, in which, Trần Hậu Yên Thế has pointed out that ancient people carved in the nghê their joys, sorrows and their souls. |

Inner Sanctum: Could you explain more about the nghê, its history and its role in ancient society in Việt Nam?

The nghê is a sacred animal with a rather complicated origin. According to some historical records, the nghê is a mythical creature, originating from Buddhism.

The nghê was brought to Việt Nam possibly in the 1st century AD by businessmen and Buddhist monks from India and central Asia. The nghê was popular during the Lý reign (1009-1225). Over time, the nghê has been carved in diverse forms and materials, displaying various facial expressions and characteristics. It has appeared in various positions at the spiritual sites of the Vietnamese people.

Sấu is a kind of nghê carved during the Lý reign. It was typically placed along the sides of stone outdoor staircases. Images of the nghê were also carved on lotuses such as at Phật Tích Pagoda (northern province of Bắc Ninh), Bà Tấm Pagoda (Gia Lâm District, Hà Nội) and Sùng Nghiêm Diên Thánh Pagoda (Thanh Hóa).

Inner Sanctum: What do you think of the role of the nghê in modern society in Việt Nam and the culture ministry’s efforts to remove alien creatures from sacred and public places?

Although it appeared very early in the Vietnamese people’s lives, the nghê has almost disappeared today.

The nghê has sometimes appeared in art research books but under different names. The alien mythical creatures imitating the kylins from the Ming and Qing dynasties in China have also wiped out the nghê from sacred sites, offices, entertainment areas and the Vietnamese people’s cultural activities.

The culture ministry has banned on symbols, products and mythical animals that do not match Vietnamese customs and culture.

I think the concerned agencies should implement the ban and, at the same time, work out solutions and policies to educate the people. In particular, there should be policies to encourage design creations to re-introduce the nghê into daily life. Actually, the idea was formed during the Nguyễn dynasty (1882-1945), when artisans carved the nghê playing lutes, holding inkpots or as containers for bonsai. The nghê was even treated like human beings. So why is there no cartoon inspired by the nghê?

Inner Sanctum: Could you tell me a bit about yourself?

I am interested in cultural heritage icons that have been forgotten and negatively affected by the modernisation trend. For example, the decorative iron patterns on the windows of houses in Hà Nội, built in the early 20th century, were discussed in my book titled Song Xưa Phố Cũ (Ancient Windows in Old Streets) in 2013.

Inner Sanctum: What’s your plan for this year?

This year, I will pay more attention to the applied capabilities of nghê images. I am thinking of a funny short comic book for children based on the nghê. Maybe the title will be Cười Như Nghê (Smile Broadly Like the Nghê).

Inner Sanctum: In your opinion, what is the greatest challenge faced by painters and fine arts researchers?

I think the most difficult part of conducting research on fine arts is choosing the perspective and approach. It is better to view Việt Nam objectively, from the perspective of other countries in the region and around the world.

There should be more comparative research, which requires uniform support from research to publication. Sponsors should come from diverse sources, rather than depending solely on state agencies, even though the Government should subsidise the important cultural needs of the country.

I expect that my book on the nghê will receive financial support from the Government to get it re-printed soon. In her introduction for my book, Culture Deputy Minister Đặng Thị Bích Liên commented, “This is a valuable book and is useful for culture managers, researchers and ordinary people to develop Vietnamese traditional cultural heritage in the current period of global integration." VNS