Inner Sanctum

Inner Sanctum

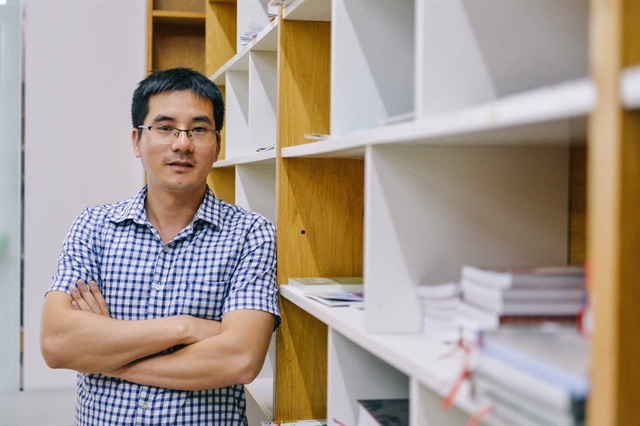

Nguyễn Quốc Vượng, 43, is a speaker and freelance translator who has delivered hundreds of lectures on reading culture and education across Việt Nam. He is also the author and translator of 100 books and more than 200 articles, many of which inspire reading habits, especially among children. Văn Học talks with Vượng.

|

| BOOK LOVER: Speaker Nguyễn Quốc Vượng. — Photo bookhunter.vn |

Inner Sanctum: You’ve taken part in multiple events, particularly talks on reading and reading culture at schools, universities, private businesses, and government offices. What has been the biggest challenge in this work?

I began encouraging reading on a broad scale in 2017 and have continued ever since. These activities include inspirational talks, consulting on library development and book collections, and running courses on reading skills.

After seven years, I’ve seen a shift in public awareness—especially within educational and cultural institutions. However, our efforts are still like a drop in the ocean, as reading culture has long been undervalued in society. Today, children and adults alike are overwhelmed by audiovisual culture.

This work often feels like "fighting windmills". It demands perseverance in pursuing long-term goals while constantly adjusting one’s approach. Many parents still focus solely on extra classes and grades, overlooking the value of reading. At many schools, teachers prioritise competitive achievements for their reports over meaningful educational development. Shifting these deeply ingrained mindsets remains a major challenge for reading advocates like myself.

Inner Sanctum: You spent many years abroad, including eight years studying and researching in Japan. What lessons can we draw from Japan’s approach to building a reading culture?

Japan has a long-standing reading tradition, which was instrumental in its early 20th-century transformation into a global power through learning from the West. Despite enduring various historical hardships, Japan’s reading culture has remained largely uninterrupted.

Strategically, Japan has passed several national laws to encourage reading—such as the Library Law (1950), School Library Law (1953, revised 2016), Law for Promoting Children’s Reading Activities (2001), and Reading Culture Promotion Law (2005). National, provincial, and local strategies for reading culture are backed by concrete action plans.

The Book-Start programme, which gifts books to newborns, has been a nationwide initiative since 2001 and has positively shaped reading habits. Japan also boasts a vast and varied library system, including public, private, children’s, and school libraries. Provincial libraries often house over a million books.

Reading-related events like the National Year of Reading, Library Week, and Children’s Reading Week are also celebrated. At a grassroots level, over 70 per cent of schools nationwide run a "morning reading" programme, where students and teachers spend 10 minutes reading together at the start of the day.

|

| CLASS TIME: Speaker Nguyễn Quốc Vượng discusses reading culture with students of Lomonosov Secondary and High School in Hà Nội. Photo courtesy of Nguyễn Quốc Vượng |

Inner Sanctum: Many nations have become economic powerhouses by fostering reading culture and educational reforms. What lessons can Việt Nam take from them?

People often attribute the success of advanced nations to education, scientific research, and economic policies. However, these are merely the outcomes — one of the fundamental driving forces behind such progress is reading culture. Reading culture serves as both a foundation and a point of convergence for various fields, including science, technology, education, the arts, media, and publishing. Without a strong reading culture, it is impossible to cultivate geniuses, talented individuals, high-quality human resources, a knowledge-based economy, or a civilised society.

What we can learn, in my view, is to thoroughly examine the roots of development and recognise the foundational and guiding role of culture in social life and creativity.

Inner Sanctum: The Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism has since 2019 organised the "Reading Culture Ambassador" contest. Several localities and institutions have also hosted similar competitions to encourage reading culture. How do you evaluate their impact?

I have followed these competitions for years and have attended several national and local award ceremonies. In my view, these competitions have effectively promoted reading culture nationwide, reaching schools, institutions, and organisations while attracting many students and book lovers. They have also helped change families' perceptions, making parents realise that reading is just as important as formal education.

Inner Sanctum: Based on your journey of encouraging reading and insights from other countries, what immediate and long-term actions should Việt Nam take to develop a strong and effective reading culture?

At the macro level, Việt Nam needs a national strategy for publishing, education, libraries, media, and reading promotion, emphasising the value of reading culture. Policies should encourage private library initiatives, reading promotion funds, reading-related awards, and the mobilisation of social resources to support reading activities for different audiences.

We must recognise that reading culture is the foundation for a knowledge-based economy and a civilized society. Reading is learning. If students lack a habit of reading, do not know how to read books, or do not enjoy reading, they are not truly learning or capable of self-learning. When learning is disconnected from reading, it becomes mere test preparation for good grades. Once exams are over, students stop reading.

Thus, encouraging reading is the best way to support educational reform.

At the micro level, families can start by building home libraries, with parents actively reading books and reading to their children from birth to age six. Encouraging children to read and enjoy books as they enter school is crucial. Parents can collaborate to form book clubs for sharing and learning from each other while opening their home libraries for communal use. VNS