Politics & Law

Politics & Law

|

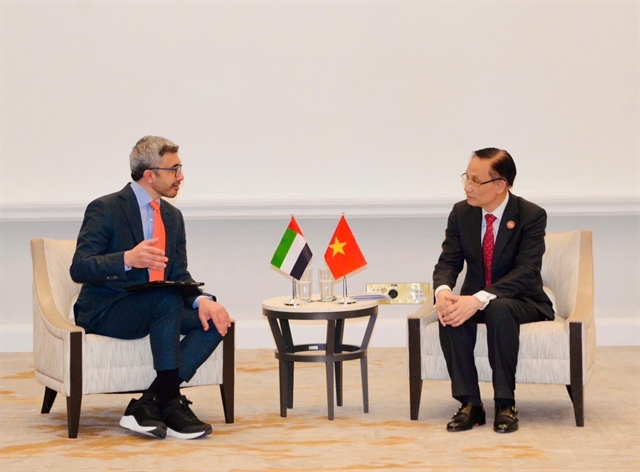

| A drugs trafficker on trial, who was sentenced to death in 2020. Drugs trafficking is no longer liable to death penalty since July 1, following a recent criminal policy reform. VNA/VNS Photo |

Compiled by Lê Việt Dũng

In a sweeping and unprecedented legal reform, Việt Nam has slashed the number of offences subject to capital punishment to just 10, marking the country's sharpest move in a decades-long retreat from the death penalty.

The revised Penal Code, passed by the National Assembly on June 25 and effective from July 1, 2025 abolishes capital punishment for eight more crimes, including corruption-related offences and certain national security violations, continuing what legal experts describe as a deliberate and long-term strategy of gradual narrowing of the scope of the death penalty.

Officials say the reform reflects shifting legislative thinking in Việt Nam and brings its criminal justice policy closer to international norms.

"Slightly over 50 countries out of 193 UN member states still retain the death penalty in law or practice," Minister of Justice Nguyễn Hải Ninh told legislators during the NA June session, calling the reform a historic legal milestone in line with both national development goals and international obligations.

Capital punishment in Việt Nam has never been treated lightly. Article 40 of the 2015 Penal Code classifies it as a 'special punishment', applied only in cases of 'especially serious crimes'.

Since 2019, the only legal method of execution has been lethal injection, replacing firing squads as part of an effort to reduce suffering for the condemned and alleviate the psychological burden on execution personnel.

The procedure involves three chemicals: one to induce unconsciousness, one to paralyse the nervous system, and one to stop the heart.

But the deeper transformation lies in the steadily shrinking scope of crimes for which the death penalty can still be applied.

In 1985, Việt Nam's first Penal Code listed 29 death-eligible offences. Following economic reforms and social restructuring, the number rose to 44 in the 1990s amid concerns over national security and social order.

The 1999 Penal Code reversed course, cutting that number back to 29. In 2009, it dropped to 22; by 2015, just 18 crimes remained punishable by death.

The latest reform, taking effect on July 1, was the boldest yet - eliminating capital punishment for eight more offences, leaving only 10 crimes where it can be imposed.

What was removed, and why

The eight offences no longer liable to the death penalty are: acts to overthrow the people's administration, espionage, sabotaging national security infrastructure, manufacturing/trading counterfeit medicine, illegal drugs transporting, embezzlement, bribery and waging a war of aggression.

The reasons behind the reform are strategic, political, humanitarian and diplomatic. According to lawmakers, the move reflects the Communist Party of Việt Nam's policy to institutionalise judicial reform and a more humane criminal justice system, in tandem with the country's rising international profile.

"It helps build legal compatibility with key international partners and facilitates extradition and legal cooperation," Justice Minister Ninh added.

As of July 1, the following 10 crimes remain eligible for the death penalty: treason, insurrection, terrorism against the state, murder, rape of a minor under 16, illegal production of narcotics, drug trafficking, acts of terrorism, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Observers say the list reflects the government's 'red line' policy, signalling an uncompromising stance on threats to national security, serious violence, and major narcotics crimes.

Perhaps the most debated aspect of the reform is the removal of the death penalty for corruption-related crimes, specifically embezzlement and bribery.

Under the previous law, a provision had already allowed for death penalty waivers in such cases if the convicted voluntarily returned at least three-quarters of the stolen assets and actively cooperated with authorities in the investigation.

The 2025 amendments take this principle further: although capital punishment is abolished for those crimes, life-sentenced offenders are now only eligible for reduced sentences if they meet the same restitution and cooperation thresholds.

This formalises a strategic trade-off: leniency in exchange for asset recovery, which officials say is essential for ensuring effective enforcement and discouraging asset concealment.

|

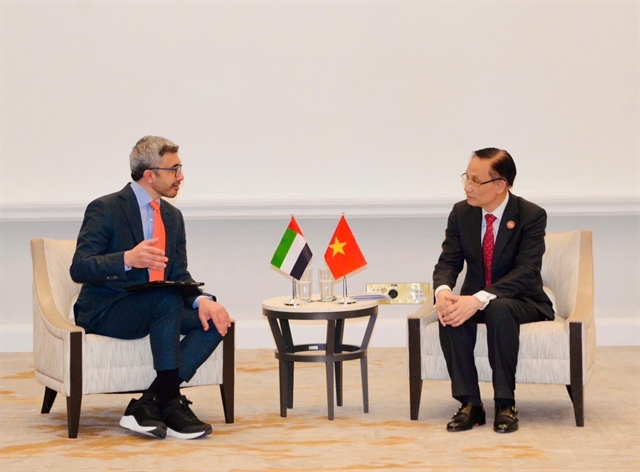

| Real estate tycoon Trương Mỹ Lan was sentenced to death in December 2024 for embezzling an estimated US$27 billion. However her sentence could be commuted to life imprisonment following a recent criminal policy reform. VNA/VNS Photo |

The law also introduces a retroactive clause that reflects the humanitarian rationale behind the reform. Those already sentenced to death for any of the eight abolished offences, but whose sentences have not yet been carried out, will not be executed.

Instead, their sentences will be commuted to life imprisonment by decision of the Chief Justice of the Supreme People's Court.

Legal analysts view this as an important signal that new criminal code amendments should apply immediately, even to those already judged, reaffirming the system's consistency and humane orientation.

Supporters and sceptics

The reform has provoked hot debate, both in parliament and society. Proponents argued that it affirms Việt Nam's commitment to human rights, aligns with global trends, and mitigates irreversible judicial errors.

NA Deputy Nguyễn Thị Việt Nga of Hải Dương emphasised that abolishing the death penalty should be seen not as softness, but as "a more appropriate legal choice that respects human dignity".

Lawyer Nguyễn Thành Công of HCM City's Bar Association, writing in a June commentary, echoed this concern, noting that no legal system is immune to error. "When a wrongful conviction ends in execution, the damage is permanent," Công said.

But the case for reform goes beyond moral and legal principles -- it also touches on Việt Nam's place in the global system.

Maintaining the death penalty, some experts argue, can create barriers to international cooperation, especially with key partners such as the European Union, which regards abolition as a precondition for full legal and diplomatic engagement.

Judicial cooperation, particularly in extradition, is another concern. Many countries refuse to extradite suspects to jurisdictions where they could face execution -- a stance grounded in the international principle of non-refoulement.

By removing the death penalty from more offences, Việt Nam has made its legal framework more compatible with that of its partners, thereby facilitating smoother collaboration on transnational crime.

Some lawmakers, however, fear the reform could weaken deterrence, especially for crimes like drug trafficking or producing fake medicine.

"Counterfeit medicine can kill in silence - it's mass murder," argued NA Deputy Phạm Khánh Phong Lan of HCM City, who believes some offences still warrant the death penalty to send a clear and powerful signal to criminals.

Within ASEAN, only Cambodia (1989) and the Philippines (2006) have fully abolished the death penalty. Other nations, including Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar, still apply it to various crimes. Singapore, in particular, retains mandatory death sentences for certain drug offences.

By contrast, Việt Nam’s reform puts it closer to the global majority. As of 2024, 113 out of 193 UN member states -- nearly two-thirds -- had abolished the death penalty either in law or in practice.

While not an outright abolition, Việt Nam’s 2025 reform represents a calculated realignment of criminal policy. It sends a message that the state can uphold justice, security and accountability without relying on the most extreme punishment.

For now, the death penalty remains, but for fewer crimes, under stricter conditions, and with clearer paths to clemency. In a region where capital punishment remains entrenched, Việt Nam’s cautious but determined steps may signal something deeper: the quiet transformation of a legal philosophy, one reform at a time. VNS