|

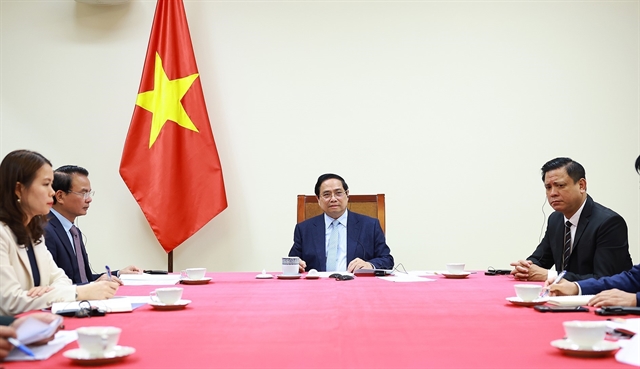

| Deborah Greenfield, Deputy Director-General for Policy at the International Labour Organisation (ILO). |

Deborah Greenfield, Deputy Director-General for Policy at the International Labour Organisation, spoke to Viet Nam News reporter Thu Vân about the Vietnamese Government's efforts to change its labour laws in line with requirements on labour rights in free trade agreements it has recently ratified, like the CPTPP and the EVFTA, as well as the challenges ahead in the world of work.

Việt Nam has recently ratified the CPTPP and signed the EVFTA, and these two trade agreements include provisions on labour rights and require the country to make certain changes to its labour laws. Việt Nam has made changes to its labour code, ratified the ILO Convention 98 and plans to ratify Convention 87 on the freedom of association by 2023. How do you evaluate such efforts by the Government?

First I want to congratulate Việt Nam on ratifying convention 98 on the right to and collective bargaining and organising. This is really a landmark for Việt Nam in its ambitious efforts to really integrate itself into the global economy.

The principles in convention 98 and convention 87 are prerequisites for participating in many trade agreements including the CPTPP and the EU-Việt Nam free trade agreement, so Viet Nam is making huge strides in integrating itself into the global trading system, moving up the value chain, and also creating the kind of a level-playing field and inclusive development that its trading partners are also committed to and want to see for Viet Nam.

The country's done a remarkable job in its efforts to revise the Labour Code. We know that there is more work to be done but, you're on a quite a sustainable path to achieving the results of true reform. Convention 105, for example, on forced labour, or Convention 87 on freedom of association, will come in due time as you continue on the path of economic and social upgrading and inclusion. So we're delighted to help Việt Nam in any way we can in working to integrate the principles of our conventions into your Labour Code.

Of course it's not simply a matter of ratifying a convention. The real challenge is to make sure that the commitments on paper are realised in practice. Is there a system of collective bargaining that works in practice? Is there a dispute resolution mechanism? How are wages set and are they set fairly? What is the nature of gender equality and non-discrimination in the country? We are working with the Government, with social partners in Việt Nam to make sure that you have all the tools necessary to implement the conventions.

Ongoing economic global integration will require further development of human resources. But like many other countries in the region, Việt Nam has a serious mismatch between the education, skills and experience needed to find and keep a job and the current content of education and training. What recommendations or support can the ILO provide regarding this matter?

We know that skills development is such an important component of the future of work.

Every country faces skills mismatches no matter where it is, what's its economic development stage, so we need to think about skills development systems in a holistic way. What we need to think about is lifelong learning. Technology is moving and changing the world of work at such a rapid pace that it will not be enough to have skills for one job when you enter the labour market and use those skills through the rest of your life. People will need to be skilled and re-skilled throughout their lives.

So I like to think of this in three parts. One we need a skills anticipation system. What are the new skills that will be necessary? And that requires the co-operation between enterprises and government and workers' organisations.

As the parties come together to think about what are the industries that the country wants to invest in to move up the value chain, to move into that upper middle-income category by creating decent jobs.

Second, we need to design effective governance systems for skills. How do we deliver skills? When do we deliver them? And how will we allow workers to anticipate that their skills will become obsolete, and when is the moment for them to get training and retraining? They need time off from their jobs. They need support and that requires strong social protection systems.

The third aspect of this is how we finance skill systems and how do we share those responsibilities. A good skills development system is expensive.

We would say that governments and enterprises need to share those responsibilities according to national circumstances. Workers then have responsibilities - they need to take advantage of the opportunities that are given to them.

This is a comprehensive system that needs to be developed through tripartite social dialogue.

Việt Nam’s labour market is set to be increasingly affected by technological progress. Many here are concerned about the impact technology will have on the labour market, for example through automation. What is your opinion on this?

You know the first research on technology was quite alarming because it said almost half of the jobs that we're looking at were going to disappear. We think that's not quite the case. Further research has been done and it's more likely that technology will change parts of jobs. Certain parts of jobs will disappear as a result of technology. But instead of having a pessimistic look at technology, the ILO is working with its member states, including Việt Nam, to look at this as a matter of policy choices.

We also need to broaden our view of technology, and not look at it simply as a job creator or job destroyer, but look at how technology can enhance the work that we do. How it can really improve what we call decent work? How can technology allow us to make sure people aren't working too many hours? How can technology make sure that people are able to move their pensions from one job to another? How can technological developments help the safety and health conditions at the workplace?

So we see this as a huge opportunity, which requires the right policy choices, anticipation and planning. But we are optimistic about technology because we have the capacity, we have the research, the evidence base, and we can have the political will to create the policies that make technology work for us.

This year, the ILO has added a new convention to its body of international labour standards. That is Convention 190 on the elimination of violence and harassment in work. Why is this convention unique, and what would be the steps if Việt Nam wanted to ratify it?

This is a landmark convention for the ILO and for its 187 member states. We started working on this convention several years ago before the #metoo movement, before all the publicity about sexual harassment and violence in the world of work. So it's timely but we were in a sense ahead of our time with developing the convention. This is the first international standard that deals with violence and harassment against both men and women in the world of work and that's why it's so groundbreaking.

First, it defines violence and harassment as a range of behaviours that have the intention of, or will lead to, resulting in harm to workers and others it defines in the world of work. Then it requires states that are our member states to, through laws and regulations, define and prohibit violence and harassment at work, and to take steps to prevent violence and harassment and to educate people about violence and harassment in the world of work.

But I have to say the convention was designed so that it can be ratified by as many countries as possible. It doesn't require the impossible. It requires strong but reasonable measures to deal with this really quite alarming issue at work. Countries will need to examine their laws and their practices, make changes where appropriate. They'll need to deal with the workers and employers' organisations to develop a culture that does not tolerate violence and harassment against men and women in the world of work.—VNS