Expat Corner

Expat Corner

For most expats, moving to a new country is a daunting experience. Transposing one’s life to a new location is difficult enough, but the added hurdles of language barriers and cultural contrasts can make the move a lot harder.

|

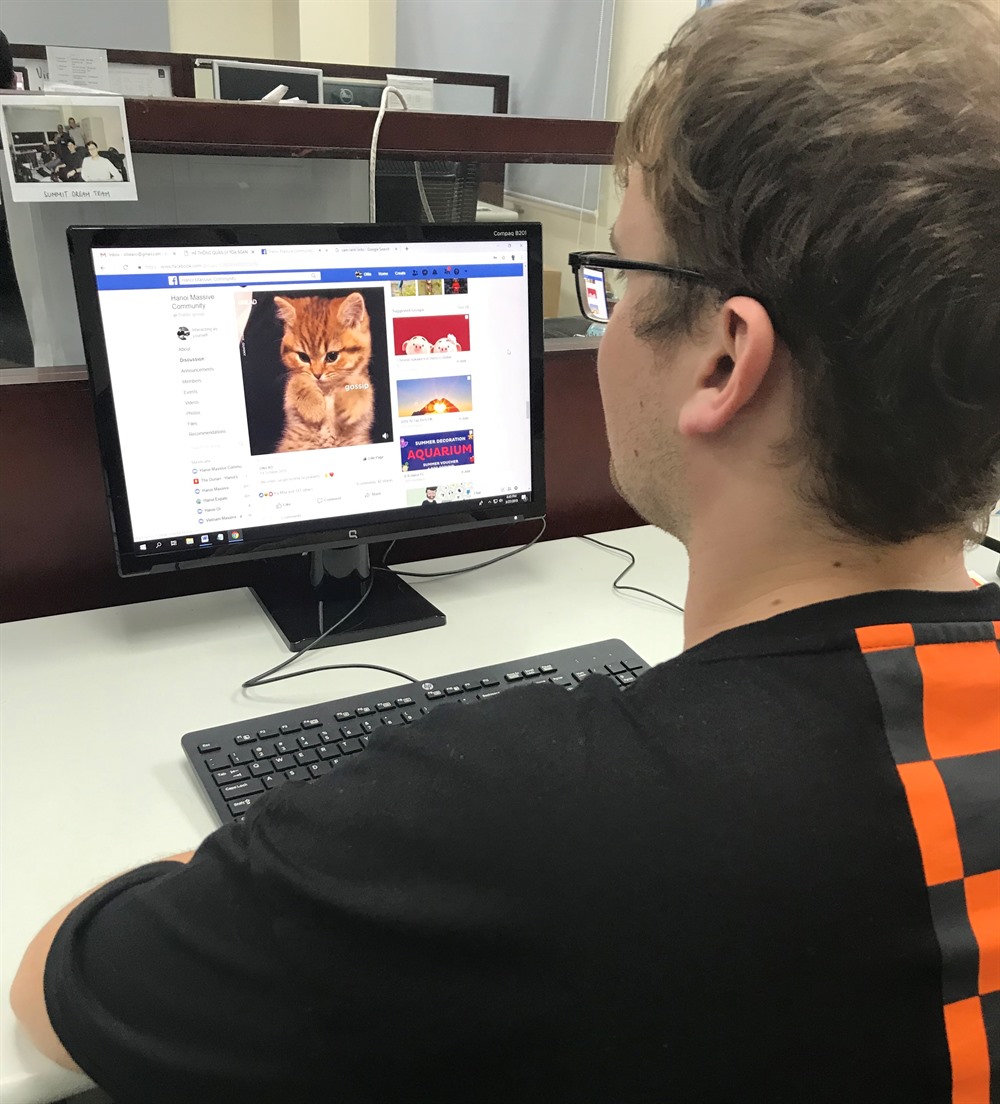

| Addicted: Social media has facilitated the spread of knowledge, but at what cost? VNS Photos Ollie Arci |

by Ollie Arci

For most expats, moving to a new country is a daunting experience. Transposing one’s life to a new location is difficult enough, but the added hurdles of language barriers and cultural contrasts can make the move a lot harder.

In addition to democratising the internet, social media has made expat life a lot easier. Facebook, in particular, has allowed the creation of a virtual town square, where neophytes and veterans of a particular town or city can gather and share information and tips on how best to navigate your new home. There are no stupid questions, and, even if there were, someone has probably asked them before.

Among the plethora of groups are those dedicated to finding jobs or apartments, marketplaces for sellers and conferences of self-confessed gastronomes, alongside other, more general, venues for chat. Some of these enjoy the participation of thousands, if not tens of thousands, of users.

Social media, for many people, is now a completely necessary part of life. In Việt Nam, Facebook facilitates a significant amount of trade and business – it’s not a stretch to say that livelihoods depend on it. For expats it is often the first port of call, more local than a Lonely Planet, helping forge connections in a new place.

The ideal of the virtual town square, where genuine actors act in good faith, has been proven a fantasy. There are undeniable benefits to social media, and bringing a diverse and disparate expat community together is certainly something to be celebrated. The success has also been its downfall, with the rise of bots and trolls, the fact that scandal and intrigue garner more likes, comments and shares than any wholesome content.

The anonymity of the platform means that people can reconstruct their identities and say things they otherwise wouldn’t. This is especially true when the identity in question has already moved from their home to live overseas. Suddenly, everyone is a philosopher, photographer or psychologist. The flattening of content creation cheapens the previous bastions of truth, and the old gatekeepers of information are relegated to the sidelines. News is playing catch up, but the sad fact is it will never catch up with the way gossip spreads online.

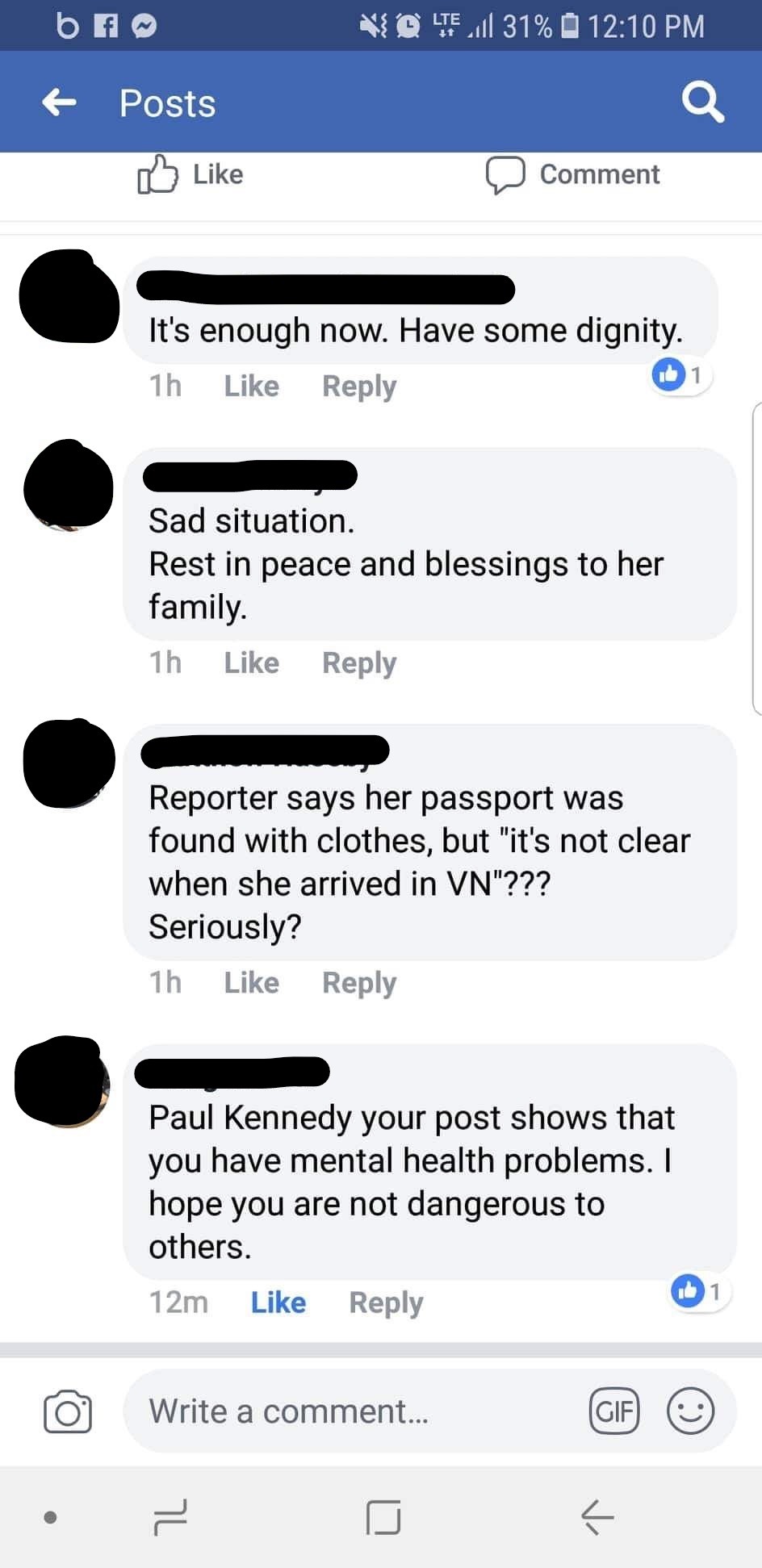

The age of instantaneous information has uncovered the dark side of social media, the one that every few weeks or so rears its head. The most recent example being the tragic death of a young woman in Hà Nội. Like in any social group, rumours travel fast. The first indications of the incident were uncensored images shared on Vietnamese Facebook groups. These quickly made the leap onto their English counterparts, and before long the death of a young woman was being shared ad infinitum along with all details that could be gleaned from her own Facebook profile.

It’s sickening for any parent to find out their child has been involved in some sort of accident, even more so when the news is broken via half-truths on your mobile phone screen. Indeed, for many of us, our first click of the day is not the news, but the newsfeed.

Before the media had a chance to pick up the story, many of the details were already known. The girl’s Facebook page was quickly littered with well-intentioned if misplaced expressions of mourning from strangers, while family members sifted through searching for scraps of fact.

This, unfortunately, is the new reality. Following the spike in posts on the topic du jour comes the outrage and anger, the blame and digital lynch mob. The pattern repeats until the next subject attracts ignominy. Whether it’s a cancelled festival or a thoughtless comment, the sanctimonious brigade will not be far behind. The court of public opinion is harsh, even more so when judgement is handed down immediately. Evidence now lives forever on servers and in screenshots.

Rubbernecking at someone else’s misfortune will never go out of fashion, and whether through algorithms or graphic design, our social media overlords have deftly engineered our experience to be as addictive as possible. Gamified, the virtual town square becomes less a forum and more a fight, with cheap point-scoring elevated above human dignity. The rules are clearly different from those applied to reality, and so they should be. These platforms will only become more pervasive, and no one is suggesting anything so draconian as a code of conduct. Already, legal systems across the world are wising up to the threats of online speech, protecting businesses from defamation. Still, the individual is largely unprotected. A rude comment in a bar may get you into a scuffle, but from safe behind a screen there’s little chance of repercussion. The democratisation gives everyone a voice, the true target of freedom of speech.

As a society and community we have not yet come to terms with the risks of living most our lives online. There will be many more scandals to come, and the impulse to post and comment on them will endure. Social media will continue to be source of knowledge and aid to expats, it will help in the search for labour, leisure or love. We will experience more explosions of scandal and ensuing opprobrium. Hopefully, at some point, there will be the realisation that we can and should treat someone’s avatar as we would treat their face. VNS

|

| Backlash: Anonymity online means that everyone is an expert. |