Economy

Economy

Võ Trí Thành*

|

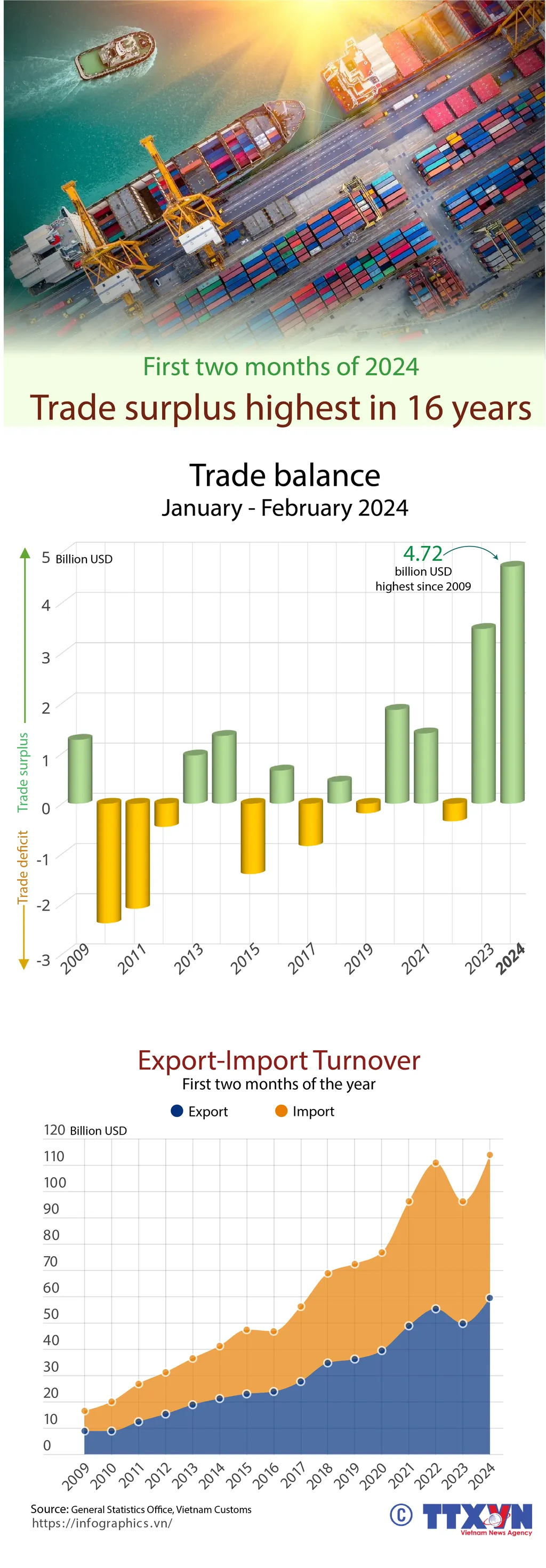

The General Statistics Office (GSO) has announced that Việt Nam’s merchandise trade surplus reached US$4.72 billion in the first two months of the year, higher than the figure of $3.5 billion reported during the same period last year.

A trade surplus is an economic measure of a positive balance of trade, where a country's exports exceed its imports.

In fact, the country’s exports in the January–February period were worth $59.34 billion while imports were valued at $54.62 billion, representing an increase of 19 per cent and 18 per cent year on year, respectively.

Theoretically, countries with trade surpluses will have many advantages. They will see their manufacturing sector improved, volume of goods sold to another country increased, and more work opportunities created in businesses operating in sectors that they have comparative advantages.

Trade surplus means the inflow of foreign currency surpasses the outflow, which can result in a rise in foreign exchange reserves, enabling the countries to pay down its debts – thus improving its creditworthiness – and strengthening its central bank’s ability to intervene in the currency market. This is particularly true in emerging or developing markets, and in countries whose economic growth is highly driven by exports. Việt Nam is not an exception.

Việt Nam started to have a trade surplus in 2012 with $284 million. Since then, the trade surplus has continuously created "new milestones". Especially in 2020, in the context of the world economy being heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, Việt Nam's trade surplus still reached a figure of $19.1 billion. In 2023, Việt Nam enjoyed a trade surplus for 8th consecutive year with a record $26 billion, nearly triple the 2022 figure.

Looking to the overall economic picture, the achievements is really plausible as they have not only contributed to stabilising the domestic macro-economy, generating GDP growth, creating jobs for workers, but also brought Việt Nam to the 22nd position in the world in terms of export turnover and capacity and to the 26th rank in international trade scale.

However, trade surplus should be assessed cautiously as in Việt Nam, there have been two problems related to the trade surplus, which makes the picture not necessarily so rosy.

First of all, the trade surpluses have been totally created by foreign invested enterprises. In 2020, foreign invested sector’s trade surplus was recorded with $34.6 billion, while the domestic business sector still had a trade deficit of up to $15.5 billion.

In the first two month of this year, foreign-invested businesses in Việt Nam posted a trade surplus of $8.25 billion while Vietnamese companies posted a trade deficit of $3.53 billion.

According to the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the foreign-invested sector still accounts for over 70 per cent of the country's total export turnover, showing the fact that the competitiveness of domestic enterprises remains weak, and their capacity is not yet strong enough to participate deeply in the global supply chain.

Besides, Việt Nam's processing and manufacturing industries also rely too much on external raw material supplies and intermediate goods because the supporting industry is not yet developed.

That foreign-invested enterprises account for about 20-22 per cent of GDP but make up more than 70 per cent of total export turnover shows they know how to take advantages of free trade agreements (FTAs) of which Việt Nam is a signatory and are enjoying most of the commercial benefits brought by our integration efforts.

Secondly, if looking more closely at the numbers, we will find it worrying that the surge in trade surplus could be thanks to imports turnover falling at rates higher than exports’ revenue.

Specifically, after reaching record high in 2022, exports last year declined by $17.2 billion, equivalent to a rate of 5 per cent while imports dropped by $31 billion, equivalent to a rate of 8 per cent.

Notably, among the four groups of imported goods (namely consumer goods, raw materials and fuel, intermediate goods and capital goods), the largest groups – intermediate goods such as components and capital goods such as machinery and equipment which account for total 70-80 per cent of the imports – decreased, reflecting a deceleration in production and processing capacity of businesses as well as a slowdown in private investment.

|

| Confectionery products of the Bảo Hưng International JSC in the northern province of Thái Bình are exported to more than 30 countries worldwide. VNA/VNS Photo Thế Duyệt |

Bright sides

This year, the Ministry of Industry and Trade has set the target of 6 per cent rise in export revenue growth compared to 2023 with a trade surplus of $15 billion.

The target shows the ministry and Government have a more cautious consideration, taking into account a slow recovery of Việt Nam’s major partners and ongoing geopolitical tensions which have no signs of easing.

However, looking to the bright side, we find that after a period of stagnation, businesses' inventory will decrease and demand may bounce back. To a certain extent, this is reflected in the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) in January and February 2024, which increased to over 50 points.

Orders from some industries such as textiles, garments and footwear also show signs of improvement. Many large businesses said they have orders for goods to arrive by the end of the first quarter of 2024.

In fact, imports of components and machinery and equipment in the first two months of the year rebounced with a 24 per cent rise year on year, which demonstrates that the private sector started to invest more in production.

According to IMF (International Monetary Fund) forecasts, world economic growth in 2024 is 3.1 per cent – slightly higher than 2023. This brings hope that world demand will recover more or less.

Other bright spots in the country’s recent economic performance is that FDI continues to maintain upward momentum (both commitment and disbursement) due to the trend of supply chain shifting; the upgrade of Việt Nam’s strategic partnership in 2023 and the market expansion thanks to the FTAs implementation.

Mindset change

Despite the bright spots, the trade sector needs to exert all-out efforts to reach the target. For a developing country like Việt Nam, maintaining trade surplus is deemed a great success of the country in the past. But creating a trade surplus with more contribution of domestic enterprises would make more sense.

To do so, the Government must take long-term measures to enhance the productivity and competitiveness of local enterprises, helping them to participate more deeply and extensively in the global supply chain.

Global tensions and a rise in nationalism have painted a picture of importers being losers. However, that’s not necessarily the case, especially when everyone is on good terms. Therefore, gaining trade surplus by all means, even exporting natural resources rather than value-added products, should not be encouraging.

Economist Adam Smith, the Father of Modern Economics, opined in 1776 that the wealth of a nation was created solely on the basis of trade specialisation and productivity improvement. He believed that trade is not a zero-sum game as it is “always advantegeous, though not always equally so, to both” (importer and exporter).

|

*Võ Trí Thành is former Vice President of the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) and a member of the National Financial and Monetary Policy Advisory Council. A doctorate in economics from the Australian National University, Thành mainly undertakes research and provides consultation on issues related to macroeconomic policies, trade liberalisation and international economic integration. Other areas of interest include institutional reforms and financial systems. He authors the Việt Nam News column Analyst’s Pick.