Society

Society

|

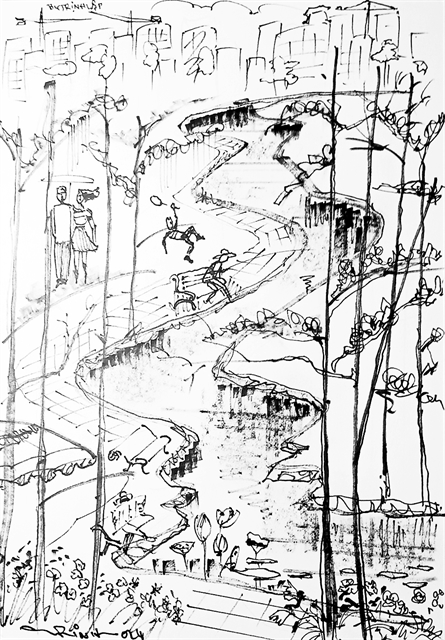

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

By Hoàng Thạch

The Tô Lịch River, once a meandering and vibrant waterway that embraced Thăng Long Citadel, now runs through western Hà Nội—a shadow of its former self.

For centuries, the river was a vital and picturesque feature of the city. It served as a segment of the Red River, flowing along the western side of the citadel, where kings would set sail. The river was named after Tô Lịch, a legendary figure and village leader of Long Đỗ, the precursor to the historic Thăng Long Citadel.

However, over the past 30 years, the river has been fragmented and reduced to a wastewater channel, carrying tonnes of sewage from Hà Nội’s rapidly expanding urban areas. The more the city grew, the more polluted and lifeless the Tô Lịch became, a far cry from the poetic verses once inspired by its beauty:

"Sông Tô Lịch vừa trong vừa mát,

Thuyền em kề đỗ sát thuyền anh."

(River Tô Lịch is both clear and cool,

My boat halts alongside yours, darling!)

Historical gem

Historical records and maps, such as the Hồng Đức địa dư [geography book] from King Lê Thánh Tông’s reign in 1490, depict Thăng Long Citadel surrounded by rivers. The Red River bordered the citadel to the east, while the Tô Lịch flowed along its northern and western edges. The rivers were not just a natural boundary, but also key trade routes, carrying goods and supplies to the citadel.

Legend has it that Tô Lịch, a benevolent village chief, opened his family’s granaries to feed locals during hard times. After his death, he was revered as a saint, and the river was named in his honour. For centuries, the Tô Lịch symbolised both the cultural and practical lifeblood of the city.

Under the Đinh, Lý, Trần, Lê, and Nguyễn dynasties, the river’s silt-laden gates were often dredged to allow small boats to navigate its waters and supply the citadel. However, by the late 19th century, during the Nguyễn Dynasty, the river’s gates became so clogged with alluvium that the Red River could no longer flow into Tô Lịch. In 1889, French colonial authorities filled parts of the river near the citadel’s northern walls, paving the way for what is now Hà Nội’s Old Quarter.

Today’s Hàng Lược, Nguyễn Siêu, and Ngõ Gạch streets trace the former path of the Tô Lịch, with Chợ Gạo Street recalling its role as a bustling rice market. What remains of the river flows from Bưởi to Hoàng Quốc Việt Street, along Bưởi Boulevard—a diminished 14km stretch far removed from its historical prominence.

For many Hanoians, River Tô Lịch remains a symbol of heritage and nostalgia. Dreams of restoring its waters to their former clarity and vibrancy are shared by those who cherish the city’s past. This hope gained momentum recently when Bùi Thị Minh Hoài, Hà Nội Communist Party secretary, made a bold statement: “River Tô Lịch shall be clean.”

Speaking at a meeting on December 4, Hoài emphasised that the city would prioritise comprehensive efforts to treat pollution in the Tô Lịch and other inner-city rivers.

“We must tackle the sources of pollution at their root to revive the river,” she said. She proposed connecting the Tô Lịch River to the Red River to flush out stagnant water and eliminate the foul odour that currently plagues it.

In the first for Hà Nội, the Party secretary—a woman in this position—has set a clear deadline: the city aims to transform the Tô Lịch into a clean, romantic waterway, worthy of pride for the capital’s residents by National Day, September 2, 2025.

To achieve this, she has instructed the city’s Department of Construction to install a water supply system from the Red River, using two steel pipes under West Lake. One pipe will provide fresh water to the Tô Lịch continuously, while the other will supplement West Lake’s water levels as needed.

Challenges ahead

Despite these ambitious plans, technical challenges remain. The city must secure approval from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development’s Dyke and Natural Calamities Management Department for the proposed solution. Over the years, many attempts to clean the Tô Lịch River have fallen short, leaving residents disillusioned about the possibility of a healthier environment.

Yet optimism persists. The Party secretary’s hands-on approach, including her recent visit to the river, has reignited hope among Hanoians. Her promise to improve the city’s water and air quality has resonated with a population eager for meaningful change.

Restoring River Tô Lịch is about more than aesthetics; it reflects a broader commitment to environmental sustainability and quality of life in Hà Nội. Clean water and air are fundamental to the well-being of the city’s more than 8 million residents. While technical solutions and government initiatives are crucial, public support and cooperation will also be essential to achieving these goals.

The Party secretary’s vision for a revitalised Tô Lịch River is a reminder of Hà Nội’s rich heritage and the possibility of a brighter future. As the city works to restore this historic waterway, all Hanoians can take pride in supporting efforts to create a healthier, more vibrant capital. VNS