Inner Sanctum

Inner Sanctum

The book “Khi đại dịch thế kỷ COVID-19 đi qua” (When the COVID pandemic is over), a commentary by writer and journalist Sương Nguyệt Minh has just been released, covering nearly 30 articles from the past two years.

The book Khi Đại Dịch Thế Kỷ COVID-19 Đi Qua (When the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Over) by writer-journalist Sương Nguyệt Minh which includes nearly 30 articles from the past two years, has just been released,

The book tells of medical workers, journalists, soldiers, benefactors and patients in their fight against the pandemic. It is also about the lessons learned in the life and death battle, as well as stories of extraordinary people during tough times. Văn Bảy speaks with the author about his thoughts on the pandemic.

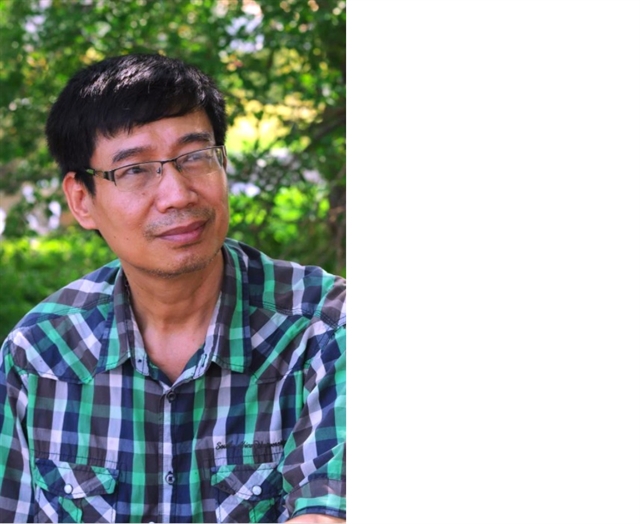

|

| Writer Sương Nguyệt Minh. Photo kienthuc.net.vn |

Inner Sanctum: What were the key reasons you wrote this book?

The more I live, travel, read and experience, the more I realise that humanity is a victim of "natural calamities and enemy-inflicted destruction" but also its own victim.

I wrote: “Day by day, people with washed-out faces hurry to make a living, go out in the morning, go out in the evening, reinforced by concrete buildings which are cool in winter and hot in summer. Humans are living in an ecologically imbalanced environment, living on this rough, diverse and painful globe.”

With the coronavirus pandemic, it was even more confirmed: Humans are victims of the virus and also victims of themselves.

Humans shouldn’t be arrogant as the Lord of all species, controlling and dominating living beings, without knowing how to live in harmony and peace in a balanced ecology, for then all species will be angry and people will receive unforeseen losses, even leading to the destruction humanity.

However, I look at my fellow human beings as well as myself as victims, with eyes that are not indifferent, emotionless or contemptuous, but pitiful and compassionate.

Inner Sanctum: When the pandemic started and you just wrote one or two stories, did you think you would write so many?

I published the first article in Tuổi trẻ & Đời sống (Youth & Life) newspaper on February 1, 2020. At that time, in Việt Nam, there were only five people infected with the virus, including two Chinese patients and three Vietnamese people being treated at Thanh Hóa Provincial General Hospital and the Central Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Hà Nội.

Before this pandemic, many universities allowed their students a week off from class. Many festivals, seminars, and meetings were postponed or cancelled. The Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Justice met and confirmed there was enough legal basis to declare a state of emergency.

I realised the situation seemed tense, and would be for a long time. I have had nearly 20 years working at a top military hospital, and am somewhat knowledgeable about infectious diseases. My friends who are epidemiologists were really concerned.

In addition to the writer's intuition, I felt I might have to write for a long time about this global health crisis. But, I didn’t realise I had written nearly 30 articles. I wrote for almost two years, but still have to write even though I would rather not.

|

| The book 'Khi Đại Dịch Thế Kỷ COVID-19 Đi Qua' by Sương Nguyệt Minh highlights humanity coping with the pandemic. — Photo courtesy of the writer |

Inner Sanctum: The pandemic is still raging but you write "When it's over," so when do you think it will be over?

The pandemic can be likened to a storm, but is different from a storm passing over the East Sea. "When it is over" is a literary meaning, not a narrative that passes with physical, geographical and time elements.

The pandemic breaks out through a commune, a ward, a district, a province and then it moves to another locality. It passes away, and it turns back again. It halts production and transport, separating people from people on a national and global scale. It also makes people reveal all that belongs to them. The pandemic is like a clinical thermometer testing people's hearts.

The pandemic passing is also a situation for the appearance of deceitful people, opportunists, profiteers, and those who are subjective, neglectful, afraid, confused, stigmatized... even insensitive to the pain of human beings. But the majority are still honest, kind, courageous, dedicated, sober people who silently do good work in the context of this cruel disaster.

Inner Sanctum: What was the hardest thing for you to say when writing about the pandemic?

The most difficult thing is to approach reality. During the war, a writer was both a writer and a soldier, participating in reality as an insider. But for the reality of the coronavirus, a writer can’t be a doctor, a nurse, or a cleaner in a field hospital to witness this fierce, most terrible thing.

A team of journalists made a recent documentary Ranh giới (Boundary), when they spent two weeks in Hùng Vương Hospital in HCM City. This reality was hot, happening, and no character had time to give a writer's experience, and no writer is so unfeeling as to take material from characters who have had too little time to treat patients and rest. They are tired and overloaded, with their life threatened by infection.

But, the writer has advantages. I and many colleagues live in the "orange zone”, separated from the "red zone". My alley is only 200m long but has four checkpoints separated with warning cords and solid iron fences. To get to the main road, I have to go through three checkpoints.

For nearly 50 days of living in those semi-quarantine areas, sometimes I was depressed. So I think the doctors and nurses on the frontlines of the pandemic as well as patients must also be miserable. It is this reality that the writer must experience and work. VNS