Features

Features

The sao la, Vũ Quang ox, spindlehorn, or Asian bicorn (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) is one of the world's rarest large mammals, a forest-dwelling bovine found only in the Trường Sơn Mountain Range of Việt Nam and Laos.

|

| The saola is one of the world’s rarest large mammals, a forest-dwelling bovine found only in the Trường Sơn Mountain range of Việt Nam and Laos. Photo David Hulse / WWF |

The sao la, Vũ Quang ox, spindlehorn, or Asian bicorn (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) is one of the world’s rarest large mammals, a forest-dwelling bovine found only in the Trường Sơn Mountain Range of Việt Nam and Laos. The species was defined following a discovery of remains in 1992 in Vũ Quang Nature Reserve. A living sao la in the wild was first photographed in 1999 by a camera trap set by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and again in 2013 in Quảng Nam Province.

The world marks July 9th as Sao la Day and raise awareness of the critical endangered animal and its scientific importance among the community.

By Hoài Nam

Viên Xuân Liên, a Tà Ôi ethnic man working as a forest ranger at the Sao La Thừa Thiên-Huế Nature Reserve in A Lưới District in the central province of Thừa Thiên-Huế, has trailed after the footprints of the sao la over the past five years in vain since he joined the forest ranger team, a forest protection initiative of WWF under Carbon sinks and Biodiversity (CarBi) project, in the Sao La Thừa Thiên-Huế Nature Reserve.

The last time he saw the critically endangered species was in 1994 during a forest patrol trip, and he has yet to meet it again.

|

| Viên Xuân Liên, a team leader of Forest Guard team in Sao la Thừa Thiên-Huế Nature Reserve, sets up a camera trap to record the movement of wild animals in the forest. VNS Photos Công Thành |

Liên, who was born and grew up in A Ho Village in A Roàng Commune of the central province’s mountainous A Lưới District, recalled that sao la and other wildlife species were once abundant in the primary ever green forests.

“It’s similar to muntjac. The sao la was one of various animals that we used to see in the forest in my teenage years. Hunting was the old trade and a breadwinner among the tribes – the Tà Ôi, Cơ Tu and Pa Cô – living in the Trường Sơn Mountain Range,” Liên recalled.

Liên said he had not known the importance of the sao la until he was recognised by the Forest Ranger model initiated by the WWF in 2010.

Liên said it’s an old story for the Tà Ôi ethnic group where young people prefer profitable jobs in towns, while communication on forest protection is booming under the strict control of rangers in buffer zones in the Thừa Thiên-Huế Sao La Nature Reserve.

The local community has become aware of the importance of the endangered animals and the forest due to regular communication programmes organised by the forest guard team in the Sao La Thừa Thiên-Huế Nature Reserve over the past six years, according to Liên.

“Local born forest guards play as crucial communicators among ethnic communities. We persuade local people to stop illegal hunting and logging, and get them to understand that these activities are illegal,” Liên explained.

|

| A ranger checks the route of a patrol trip using a global positioning system and a map. Rangers often take days long patrols in the forest to track the footprints of wildlife and block illegal hunting and logging. VNS Photos Công Thành |

Changes

Liên, 39, and his colleagues spend 16 days a month patrolling in the 15,500ha reserve in combination with using forest protection communications.

Their efforts have helped dismantle over 75,000 snares and destroy 1,000 illegal huts – shelters for illegal loggers and hunters.

“Rangers in the Sao La Nature Reserve in Thừa Thiên-Huế and expanded protection areas in Bạch Mã National Park and Quảng Nam Province spent 38,000 days over 1,100 forest trips tracking critically endangered species as well as creating thousands of survival chances for wildlife,” said Lương Viết Hùng, protected area manager of CarBi from the WWF-Việt Nam.

“More equipment and new solutions were given to support rangers and enhance their capacity of protecting biodiversity as well as tracking the vestiges of the sao la species,” Hùng said.

He added that a terrestrial leech – a regular blood sucking worm in tropical primary forests – has been used to recover blood samples for DNA identification of species in nature.

Hùng said over 600 blood samples extracted from leeches were sent to laboratories around the world to match with gene sources.

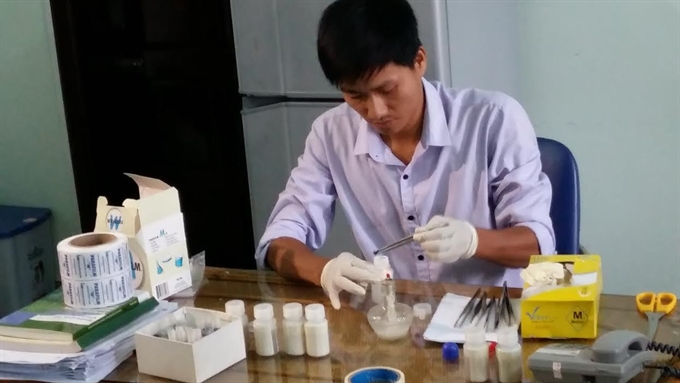

|

| A tropical leech is used to supply a blood sample for DNA identification at a laboratory. VNS Photos Công Thành |

“It’s very new research on biodiversity in the world. Forest guards are trained to collect the blood suckers in the deep jungle to identify species on a map,” Hùng said.

He added that camera traps and regular patrols had helped record the appearance and existence of the sao la and various other endangered species including the Trường Sơn muntjac (Muntiacus truongsonensis), the Trường Sơn striped rabbit (Nesolagus timminsi), the red-shanked doucs (Pygathrix nemaeus) and the Asian black bear in recent years.

Hùng stressed that traps and snares are still the toughest challenge in the Sao La Nature Reserve.

Lê Quốc Thiện, a member of protected area officer of CarBi, WWF-Việt Nam, said traps were sharply reduced by 50 percent in early 2011, but had begun increasing again in 2014-15.

“Illegal hunters do not set up snares in a mass, but hide them in multiple sites to make sure they catch animals. None of the wildlife species can completely escape from this trap system,” Thiện said.

“Although local people have positively raised their awareness of wildlife protection, life hardships can still lead them into illegal hunting and logging,” he said.

He stressed that the masterminds of illegal hunting groups often come from other provinces, as locals can be easily detected by rangers.

Thiện said restaurant owners from other provinces willingly cover the costs for traps and snares, and sometimes even portable hand-made air guns.

He said easy money would lure local hunters, while punishments have yet to provide a deterrence from illegal actions.

Thiên, 28, said traps and snares are dangerous tools that can lead to the extinction of endangered animals and species, especially in the Thừa Thiên-Huế Sao la Nature Reserve where there is easily accessible transport.

He said the hunters spend one or two days in the forest setting up traps using steel wires, each with lassos on two sides of them. They then return a few days later to collect the animals they have caught.

Weasels, squirrels, muntjac deer, wild boar and civets can easily fall prey to the traps at night, he speculated.

|

| A ranger team treks in the 15,500ha of the Sao La Nature Reserve Centre in A Lưới District in the central province of Thừa Thiên-Huế. VNS Photos Công Thành |

Livelihood

Log farming and wood processing development is seen as a positive and long-term sustainable solution in A Roàng Commune.

A hectare of acacia farm can bring in revenue of VNĐ30 million, while a rubber farm can add to a resident’s coffers, Vice Chairman of A Roàng Communal People’s Committee, Viên Xuân Danh, said.

“Stories of sao la and biodiversity are regular topics at all meetings in villages, communes and primary schools. As a result, 85 percent of the 2,500-population commune is aware of the sao la,” he said

Danh, however, said that the 60 per cent of the population living in poor conditions could be a pressure on wildlife protection in the reserve.

“Local administration plans to build a wood processing plant to collect from the log farm, while local people also benefit from payments from a forest environment services (PFES) programme are both better solutions that involve local residents in forest protection.”

According to Lê Ngọc Tùng, head of A Lưới ranger station in the Thừa Thiên-Huế Sao La Nature Reserve, rangers face many difficulties in tracking poachers.

The area is out of mobile phone service range, so communication between the station and rangers on patrol is still limited in dealing with poaching.

WWF-Việt Nam has been planning an afforestation of indigenous trees including rattan, medicinal herbs and log – that exist in the forest – in changing the livelihoods of the locals.

|

| A local man shows the remains of a sao la, which was defined following a discovery of remains in 1992 in Vũ Quang Nature Reserve in Hà Tĩnh Province. Photo David Hulse / WWF |

Hồ Xuân Nhàn, a Tà Ôi man in A Roàng Commune, said he quit hunting as he recognised it was illegal and he could be imprisoned for it.

Nhàn, 37, said he became involved in the PFES programme and the forest guard team in the Sao La Thừa Thiên-Huế Nature Reserve about five years ago.

“Hunting was a favourite among ethnic groups living near forests for generations. We could not find an easier job than trekking for forestry products. If local people are given better jobs with stable incomes, they will stop poaching,” he assured.

Lê Quốc Thiện from WWF said the protection of the sao la in Việt Nam is a prolonged programme that needs strong commitment among NGOs, State agencies and the local community.

He said well protecting the environment and forest would play a crucial role in allowing the return of the sao la in Việt Nam.

However, camera traps in natural forests of Huế and Quảng Nam have yet to capture the appearance of the rare animal again. — VNS