Society

Society

For the last 21 years, there have been nearly 400 children with special needs taken care of at Hy Vọng Centre, founded by a retired doctor in Hà Nội.

|

| Founder of Hy Vọng Centre Nguyễn Thị Nga teaches children at the centre to fold clothes. VNS Photos Vân Nguyễn |

By Vân Nguyễn, with additional reporting by Minh Phương and Anh Trang

HÀ NỘI — For the past 20 years, the Hy Vọng (Hope) Centre has been home to hundreds of children with special needs.

Nguyễn Thị Nga, a retired doctor, opened the centre 21 years ago at a time when specialised schools for children with intellectual disabilities were still rare in Việt Nam.

“I founded this centre so that the children could receive the education that is dedicated for them and suitable for their abilities,” Nga said.

Nested in a small alley on Kim Mã, the centre takes care of children of various ages with different types of intellectual disabilities - autism, sequelae of meningitis, developmental delay due to epilepsy, hyperactive and inattentive children leading to developmental delay, mild cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, mild hydrocephalus, and other diseases.

Nga, born in 1942, was a student of the Hà Nội Medical University from 1961-1966 in the same class as Đặng Thùy Trâm (a battlefield surgeon and author of the bestseller Last Night I Dreamed of Peace: The Diary of Đặng Thùy Trâm).

After graduation, Nga worked in clinical care for a pediatric hospital in Sơn Tây for 12 years before being transferred to the Committee for Mother and Child Care, where she specialised in child nutrition and health. She then became head of the Mother and Child Care Division of Ba Đình District. In 1987, when the division was merged into the education sector, she was transferred and served as deputy director of the Education and Training Department of Ba Đình District.

It was during her work trips to local schools that she noticed some children sitting in the “wrong places”.

“There were children who sit there but learned nothing. They bullied others, grabbed toys from friends and did not learn anything at school,” she said.

Before retiring in 1998, she submitted a proposal to the Ministry of Education to open special training classes for children with special needs.

“It was 25 years ago and no one paid attention. The proposal got nowhere,” she said.

Only in the last 15 years, have people started to become more aware of this, she said.

|

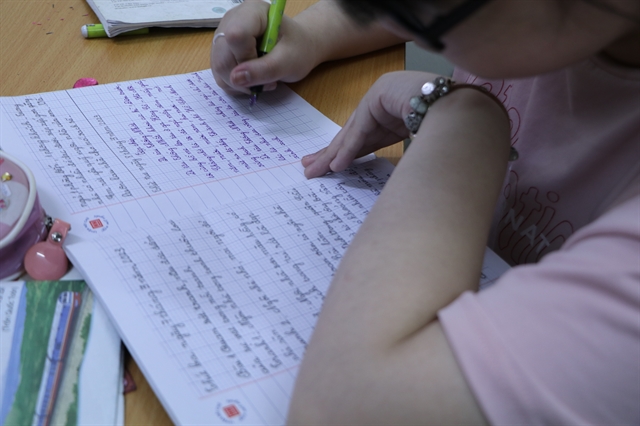

| A student learns to write at the centre. |

“Many even thought that the parents must have done something wrong or were evil and they were punished by having their children like that,” she said.

Caring for children with special needs took a lot of effort and they also face stigma from society, she said.

While she was working at the hospital, Nga also witnessed the desperate situation of patients with meningitis.

Families put huge sums of money into treatment but children returned home with sequelae from meningitis.

“The treatment was too costly, many families had to sell all their properties and after all, their child still had the disease, which was so painful for the family,” she said.

“I could feel their suffering, worries and desperation. I hope I can share what the parents feel and give them some light of hope as they have fought relentlessly for their children,” she said.

Running a centre for special children was not easy in the early 2000s. At first, she received a small group of seven to eight children.

“Our difficulty was to find a place where we could build sufficient facilities for children with disabilities. We haven’t found somewhere to have a big yard, as well as facility rooms like music, and art,” she said.

|

| The centre has received nearly 400 children so far since it opened in the early 2000s. |

“We also experienced difficulties in overcoming prejudices and judgements that stick with the disabilities those children bear throughout their life. Many parents are ashamed of their child’s illness. We had not yet had the compassion from the society, people still judged them a lot,” Nga said.

“We didn’t have sufficient financial support although we did gain some attention from the government recently. We have subsidies, but these are not much compared to the amount of money parents have to pay for treatment,” she said.

For the last 21 years, there have been nearly 400 children taken care of here.

“My goal is helping children care for their own selves, define what is good or bad for them, and how they can be good citizens of the community. We also teach them how to respect their own family members as well as how they can give, take and be grateful,” she said.

|

| Children play and study at the centre. |

“Our goal is to give children whole-hearted care. In our centre, if teachers don’t care whole-heartedly for the children if they hurt them mentally or shout at them, they can’t work here,” she said.

Lê Thị Huyền Trang, a teacher of class A2 for students with severe conditions, said before the children are admitted, the centre tests them on their awareness.

“On some children, we focus on training their skills. For those with higher awareness, we help them learn so they could have more knowledge,” she said.

“Students in my class are in quite severe conditions, so sometimes, they have abnormal actions that can bring tension to teachers and classmates. There is nothing that makes me more happy than seeing them happy in class,” said the teacher, who has worked at the centre for 13 years.

|

| Nga said she hopes to give children a specialised education that is dedicated to them and is suitable for their abilities. |

Eden Saraga, a volunteer at the centre, said: “I really like it, even though sometimes it is a little difficult with the language barrier, and I feel like I could learn a lot from the teachers here.”

“I think the work here is very rewarding. I used to work in childcare before, that is why I notice a little difference here. Children with disabilities tend to use more body language to communicate, and sometimes, they can get very creative in that,” said Eden.

Now in her 80s, Nga’s concern is to find a successor to continue her work at the centre.

“My motivation is to see the children and their parents happy. Just that,” she said. VNS