A short story by Vũ Thiên Khái

|

| Illustated by Đỗ Dũng |

by Vũ Thiên Khái

My house stood at the entrance to Trại Hamlet, whereas Mr Hậu’s dwelling was at the other end. The little community, with scores of thatched cottages in all, looked like an oasis in the middle of Phùng Village’s rice fields. Every year, in mid-August, when heavy rains poured down on dreary autumn days Hiếu, Mr Hậu’s son, and his younger sister Hạnh and I, together with some other kids, had nothing to do but stay at home listening to an ear-splitting croaking of frogs near and far. At midnight, fish appeared in the flooded rice fields around our houses to lay their eggs. Taking advantage of this rare opportunity, my father would put on a raincoat, grab a calabash-shaped bamboo basket and fishing-tackle, and wade into the submerged fields to catch fish until late morning. Those evenings we had a big plate of fish stewed with herb dumplings and a bowl of delicious fish soup for dinner.

Often when my mother left home with a basket full of fish to Xanh Market to sell, my father gave me a knowing wink. “Go to the pond to take some fish I hid from your mother to Mr Hậu’s family as a token of our friendly relationship,” he told me.

Once when I was doing this, my mother had to return home for something and caught me.

“You’re just like your crazy father!” she reproached me midlly. I just smiled in response. “Adults’ problems don’t matter to me so long as I can have fun at Hạnh’s place,” I thought to myself.

Her Dad was my father’s age, but shorter. As he was quite physically weak, he was on the co-operative tree-growing team with other old men.

Before 1945, Mr Hậu was the head of Phùng Village thanks to his wife’s father’s high position in the pro-French regime, but my father told me he knew nothing about community affairs. During the nine year war to drive the French colonialists out of the country, our villagers led political double lives: pro-French in the day and revolutionaries at night. During the later land reforms, his family was classified as middle-class peasantry, thanks to his neutrality in the conflict.

* * *

In 1954, the district chief Cầu wanted to take the whole family of Mr Hậu, his son-in-law, to join the mass exodus to South Việt Nam, but Mrs Hậu begged him to let her family stay behind to take care of her husband’s affairs and to look after their ancestors’ graves. Out of pity for his daughter, Mr Cầu gave her several taels of gold. When the land reforms reached full swing, reforming cadres took the gold.

Hiếu was like his father because of their poor health. Contrary to both of them, Hạnh, aged ten, and her mother were in good health. They had lily-white complexions, waist-length hair and were in good shape.

Coming from a needy family, Hạnh had only a few pieces of black clothing made of coarse material that didn’t fit her. I never saw her in a flowery blouse. Once, I found her mother staring at her daughter, blushing all over. Despite that, Hạnh’s eyes seemed never sad.

After the August Revolution, us four kids in our early teens in the whole hamlet– Hiếu, and his younger sister; Lác, son of the pig farmer and myself – started going to a village pre-school class. Another kid, Lừng, remained a block-headed little git. In retrospect, I remembered that we often forced him, a cracked bowl in hand, to stand motionless inside a small circle drawn in chalk around his feet. We often forgot he was stood there until we finished playing our games. His father, thanks to his great strength and skill, could lasso a wild dog with just a wave of his arm.

* * *

His father-in-law Cầu’s exodus to South Việt Nam gave Mr Hậu a heavy cross to bear. He especially worried about how his children would get on at school, would they be bullied?

“Your Mum has told me that you’re falling in love with a girl of a notorious clan of this hamlet, aren’t you?” my uncle asked me angrily once. “I’ve been so busy in the office that I’ve taken little notice of you. What’s worse, your Dad is indifferent to politics. Too bad, too bad!” he criticised me mercilessly.

“Uncle, what have I done wrong?” I asked him.

“Next month, a special training course begins in the North. I’ll register you,” he told me.

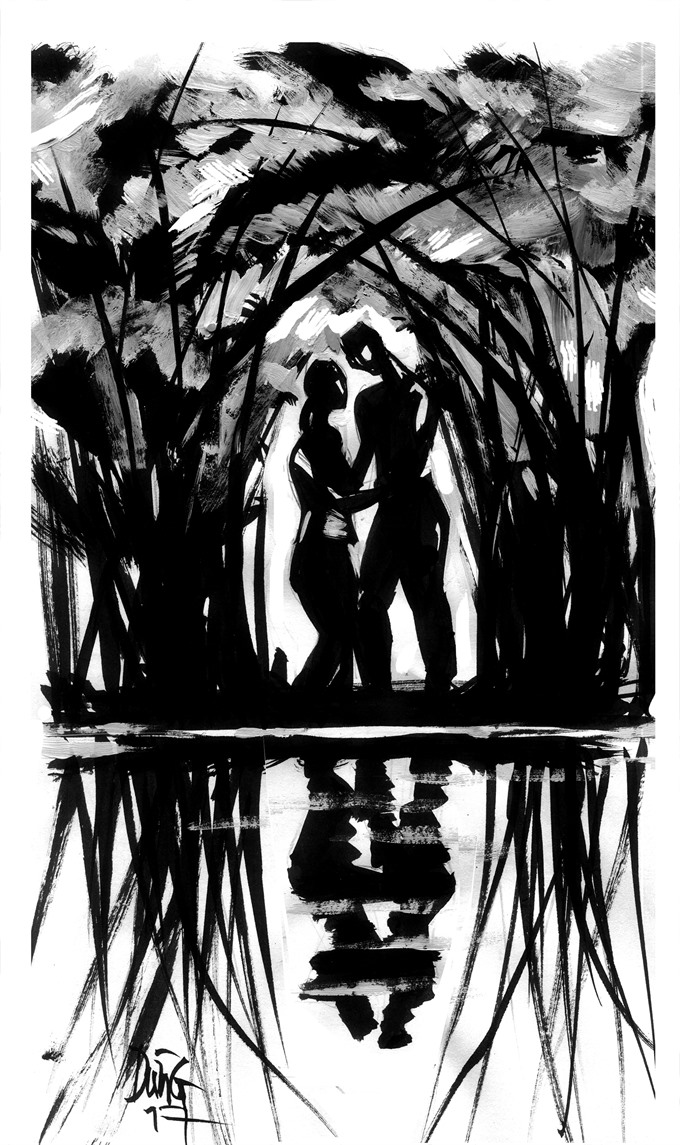

Indeed, early the next month, he took me away in his car. Before leaving, I hurried towards Hạnh’s place to tell her that I would see her later at our familiar get-together. That night, we sat together among the bamboo beside Mr Hậu’s pond, excitedly whispering sweet nothings to each other.

“Wait for me, honey! After only years of studying I’ll come back to you,” I told her.

“I’m worried, my dear,” she said to me.

Early the next morning, we left each other, eyes filled with tears. I remember that she was wearing a Huế-style purple blouse, made from one of her mother’s old ones.

When my uncle’s car passed by her gate I saw her waiting for me. She looked forlorn on that fateful day.

“Can you stop here just a few minutes?” I asked the driver when we came near to her place.

Ignoring me, he sped down the deserted earth path, on which Hạnh and I, hand in hand, had walked to school together, dreaming of a happy life together.

Unfortunately, I didn’t know I wouldn’t be able to come home for years. I didn’t know that her big hug on that last night was the last one in her lifetime. In the end, we were nothing but two grains of sand in the turbulent storm of life.

After twelve years, three months and seven days, I came back to Trại Hamlet. By then our country had been reunified for many years. Sadly, Mr Hậu’s pond was nowhere to be seen. In its stead was a wide concrete road going past the cultural house of the village and leading to the headquarters of the commune people’s committee.

In my old house, only my father with his white hair and bushy beard was left. My mother and several of Hạnh’s relatives, together with hundreds of Phùng Village residents and their children had been killed by bombs from American planes along the banks of the Đáy River.

“What about Hạnh, dear Dad?” I asked.

“She died a terrible death. Her body was found hanged from a bent bamboo tree beside her pond, just like the son of the chief of Phùng Village,” he answered.

At once, I rushed towards her house and found Hiếu in the centre of his courtyard. It seemed he had heard of my homecoming before. He had stood there, waiting for me.

“Two years after you left, she died young, hanged on top of a bamboo tree beside our family’s pond, where both of you usually sat at the water’s edge,” Hiếu said to me. “That late evening, in a purple silk blouse, she went away. Before leaving, she left this notebook for you,” he added, handing it to me.

I read the entire booklet, page by page. It recorded what had happened to her from the morning she stood waiting for me by her gate staring at me for the last time.

That afternoon, Hiếu and I went to her grave to pay homage to her. Both of us bowed down before her tombstone, eyes brimming with tears. I imagined that that evening, she had her Huế-styled purple blouse on, the colour of faithfulness, an image I kept in my memory throughout our prolonged separation.

Below are her diary pages

Date…, month…, year 196…

Darling, this afternoon, you asked me to go to the cinema to watch a new film as usual. I waited and waited for you at the normal place in vain. After that I had to go to your house. Your dog wagged its tail to welcome me. Behind the door partly covered with a blind was a mantle lamp in the centre of the table that lit up the whole room. I saw your younger uncle sitting beside you and your father. Recognising your uncle’s voice echoing out loudly I stopped abruptly outside to eavesdrop.

He was began criticising you mercilessly. “Next month, a special training course begins in the North. I’ll register you,” he told you.

I felt as if the ground under my feet was sinking. I was so dazed I couldn’t even find my way home.

Date…, month…, year 196…

I had such a high fever that I had to lie in bed for three days. Not until noon of the fourth day, did I rise.

“Why do you look at me so strangely?” asked my mother. “Do you recognise me? Why do you look miserable? You still have us by your side: your parents and elder brother.”

I grasped her icy hands. She hugged me tightly, crying.

The next morning, she told me about her puppy love as if she wanted to ease my tension.

“I naively fell in love with a farmer who had been a young servant for my family since his childhood. Of course, it was against the wish of many members of my family. My father once roared, ‘I’ll have your hair shaved completely and let you drift out to sea on a bamboo raft.’

“Meanwhile, my elder uncle from Hà Nội warned me. ‘If you decide to marry him, I’ll let my men beat him black and blue before putting him in prison,’ he said.

“My mother had died a long time before, so I could hardly find anybody to stand up for me. I once even thought of suicide. One night I tiptoed to our family’s pond. When I put my feet in the icy water I seemed to hear your grandmother’s voice, ‘If you die young, you think that your mind would be at ease, but you’re quite wrong. Your lover will be punished for his whole lifetime by your stubborn brother.’ After, I slowly retreated back home, and left the rope somewhere behind.”

At this point my mother ended her depressing story.

That was why her eyes always looked so sad.

Date…,month…, year 196…

On the morning when I watched your car shooting away at full speed, I knew I had lost you forever.

I remembered that the year before the local authorities had refused to provide a certificate for Miss Huệ, the grown-up daughter of former canton chief Kiểng, to marry a railway engineer working nearby as her family was ranked as the landlord class.

“Obviously, their social classes were different! As for us, how could we have bridged such a wide gap between our two families?” I asked myself.

When American planes attacked the North, most young people went to the frontlines. In Trại Hamlet, there were only two youths left: Lừng and Lác. For some reason, they were both exempt from military service. While Lác became a deputy chief of the hamlet’s production team, Lừng was still a wasteman. Whenever Lác saw me he would try and chat me up.

“Shut up!” I said to him. “If you were the only man in the world, I still wouldn’t marry you,” I retorted.

“Well, I guess that leaves you with Lừng,” he told me.

“No problem! He’s much better than you.”

Date…, month…, year 196…

To my surprise, when I finished my field work, returning home I found my parents receiving Lừng’s mother and her younger sister-in-law with three high-quality packets of tea on the table. Both strangers stared at me for a short while before leaving.

“They came to ask for Hạnh’s hand in marriage, didn’t they?” Mum asked Dad. He just kept silent.

“Have you accepted their proposal?” Mum asked again more loudly. Dad remained quiet.

“Oh dear, kill both of us before you agree!” she screamed.

“In wartime, how can we find an honest young man?” Dad replied a few seconds later. “Moreover, with the promise of Lừng’s younger uncle to offer Hiếu a place in college, how could I object? Anyway, I haven’t yet.”

My mother moaned bitterly. “Do you know that you’re going to ruin our daughter’s life?” she reprimanded him.

“I agree, Dad and Mum! You’d better answer them as soon as possible,” I blurted out with a broad smile.

Mum’s face went pale. She stared at me suspiciously.

“After losing my sweetheart, my heart died of sorrow. It doesn’t matter if it ceases beating again,” I said to myself.

Date…, month…, year 196…

After graduating from the village secondary school, my elder brother Hiếu entered the provincial primary teacher’s training college thanks to his ability rather than due to any favours. A week after Hiếu began his studies, Lừng and my wedding took place. I came to his house as a reluctant bride. During our first night as a couple, we lay in opposite directions. We were separated from each other by a long pillow. My husband fell asleep before anything could be consummated. He did the same the following nights. Every night my nuptial bed was shared by two miserable humans: a forlorn wife and an impotent husband.

However, time and again, I dreamt of sitting near my family’s pond, alone with you.

Date…, month…, year 196…

I often dreamt of my mother in the middle of the rice fields. She just stared at me with her inquisitive eyes. Time and again, Lừng’s mother would check to see if I was pregnant by examining the white tulle cloths I hung behind the kitchen. “Nothing special!” she said in a despairing voice.

Days later, I discovered that the door latch of my room was no longer in its former place. One night my door was ajar and I heard several light footsteps. It was Lừng’s mother with an electric torch in hand. At the sight of the pillow lying between us, she dropped it onto the floor.

Date…, month…, year 196…

One afternoon, I returned to my own parents’ place rather late. On my way home, after finishing the field work I walked past your gate, I heard a loud call echoing behind my back. It was your father. “Hạnh, get in, please. I’d like to talk to you for a few minutes,” he told me.

We sat on the bamboo plank near the foot of a longan tree. After a short silence, he began his story. “Your father was taken in by the dog-meat butcher’s brother. I was told that the guy is merely a seal-keeper with no power to ratify any CVs,” said your father. “Hiếu’s admittance into school was normal. So, there were no problems relating to the discrimination about your family’s social class. Your miserable living conditions make my heart hurt greatly. I also pity my son’s unlucky destiny.”

“It doesn’t matter much to me now, kind-hearted old man,” I said. I burst out crying. I took pity on him, on my mother and on myself.

Date…, month…, year 196…

“I married you to my son not for you to play tricks on me,” warned my mother-in-law one morning.

“Mother, what have I done wrong?” I asked.

“We need you to give birth to a baby boy, that’s all,” she retorted bluntly.

A few minutes later, she calmed down: “My dear daughter-in-law, take pity on us by offering us a son. I beg you,” she said.

“So far, it’s my family that has been cheated by yours,” I replied.

Date…, month…, year 196…

After many hot arguments between me and her, I was suspicious of her. The dog-meat butcher also stared at me treacherously. What’s more, Lừng stayed at his uncle’s house for many nights.

I decided to hide a knife under my pillow before going to bed. I also wrapped myself with a mat. Unexpectedly, one night when I had just fallen asleep I found my parents-in-law rushing in and tying me tightly with a strong rope. They attacked me brutally.

“If you give birth to one baby boy for us to maintain our ancestry, we’ll set you free,” she told me. Without waiting for my reply, she stripped me naked and spread my legs wide for her husband to violate me.

Date…, month…, year 196…

The next day, I made up my mind not to tell my parents about the rape. “The die is cast! If they knew what happened, they would do nothing, but die of shame,” I said to myself.

Returning to my home, I tried to forget what happened. All I could do then was put this diary in Hiếu’s desk, as my last act in life. I did not dare to say farewell to my parents either, because I was afraid that I would cry in front of them. I brought with me my Huế-styled purple blouse previously concealed in my mother’s bedroom. Gone were the sweet memories for my mother and the pure heart set aside for you in this piece of clothing! I would put it on this night before going away to the eternal life of my dreams beside you.

At midnight I will go to our pond, look for the rope previously left forgotten somewhere by my mother. I will tie it tightly round my hands. The moment I slowly release my tied hands will be my choice. I will fly towards you now, even if you’re thousands of miles away.

My lover, from tonight on I will never be afraid of anything!

Translated by Văn Minh