Features

Features

Hồ Văn Tai from Tân Phú Trung Commune in the southern province of Đồng Tháp is considered as the last artisan making fabric pictures in the southwestern region of Việt Nam with 68 years working in the craft.

by Phương Hà

Hồ Văn Tai of Tân Phú Trung Commune in the Mekong Delta province of Đồng Tháp is considered the last artisan producing embossed fabric pictures in Việt Nam’s southern region, after 68 years in the craft.

|

| CREATIVE HANDS: Tai and his wife Thủy make embossed fabric pictures together. Photo tienphong.vn |

Embossed fabric pictures were a popular form of “3D” art from 1956 to 1965. A combination of painting and craft and influenced by the creativity of artisans, the vivid pictures resembled those produced by modern 3D technology.

According to 84-year-old Tai, the artform was founded by Trần Văn Huy, a handicraft teacher in the city of Sa Đéc, in 1948.

“I was a 16-year-old student at his school, and one day, during a handicraft class, we ran out of glue so went to his workshop to find some,” he recalled. “There I saw beautiful landscape pictures Huy had made from fabric. I found them so wonderful I became determined to learn the craft.”

There were many Chinese-Vietnamese living in Sa Đéc at the time. During ritual ceremonies in pagodas or at funerals, they ordered many pieces of fabric around two metres in length and one metre wide, on which paper Chinese characters were attached. When customers ordered up to 300 pieces of fabric, apprentices at Huy’s workshop had to work day and night to finish them on time.

|

| POPPING OUT: Fabric pictures have a 3D effect. Photo tienphong.vn |

Seeing that such products were becoming repetitious, Huy came up with the idea of drawing words on thin paper and putting them on a cardboard backing. The words were then wrapped in fabric and stuffed with cotton, which made them come to life.

Applying the same method, he was able to create many pictures from fabric and extended the themes, from 3D words to animals and landscapes and portraits. Such creativity paved the way for a new artistic trend and a new artform that grew in popularity in the mid-20th century.

In 1956, Huy’s family moved to Sài Gòn and Tai followed his teacher, with both working in a restaurant. The stable jobs gave them handy salaries but the passion for art burned bright in the two men from Sa Đéc.

By chance, Huy learned about an evening class at the Painting and Sculpture Centre by painter Mai Lan and they decided to sign up. Both then worked at the restaurant during the day and studied at night.

After a year and a half, Tai graduated from the painting class and opened his own workshop. In 1960, his Trúc Lam fabric picture workshop opened its doors.

According to Tai, a finished work is made from fabric, cotton, thin paper, and cardboard, with a white silk frame as a backdrop.

|

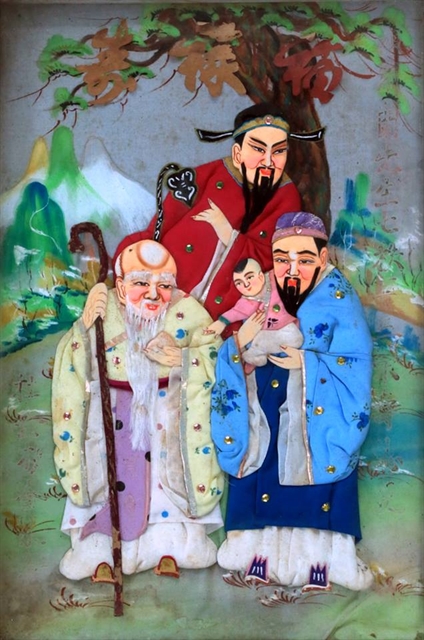

| ON DISPLAY: An embossed fabric picture from Tai portraying three deities - Fortune, Prosperity, and Longevity - was part of an exhibition at the Hà Nội Museum four years ago. Photo baotanghanoi.com.vn |

It takes much effort to create a single embossed fabric picture, he said, starting with sketches of the subject on paper, be it a person, an animal, or a landscape, then using cotton to make the shape.

The image is then wrapped in fabric like brocade or silk to create folds. Finally, the fabric images are glued to a canvas on which the background has already been painted.

Tai is fortunate to have his wife, Nguyễn Thị Bạch Thuỷ, who has always been an enthusiastic assistant

“Every step in this craft must be done slowly,” she said while carefully tearing off pieces of cotton to shape an image of a buffalo. “It requires great patience. Anyone who is quick-tempered or impulsive could not possibly pursue it.”

Thủy didn’t know how to make fabric pictures when they first met but it was the artform that bonded them together.

After they were married, their Trúc Lam workshop became increasingly crowded and agents started to arrive from the north and the south. Seven or eight young people applied for apprenticeships at Tai’s workshop.

Pictures of Buddha used to be popular in the 1960s and both teacher and students had to work long hours to finish dozens of pictures.

“The lights were on in the shop every night,” Thủy recalled about those golden days. “When the daily preparations in restaurant opposite began in the morning, we were just going to bed.”

Then came the chaos of war, forcing Tai and his wife to return to Sa Đéc. The artisan continued to make fabric pictures but on his own, without any apprentices or assistants.

“I used to take care of the cooking and caring for the children, as I didn’t know anything about the craft,” Thủy added. “But after watching my husband work by the light of an oil lamp every night, I began to study the craft and have been his assistant ever since.”

Due to falling demand and the meticulousness required, few artisans pursue the craft these days and it’s sadly falling into obscurity. Tai and his wife are the only ones now involved in the craft.

The old artisan still has customers from Mekong Delta cities and provinces such as Cần Thơ, Vĩnh Long and Kiên Giang.

He has created more than 3,000 embossed fabric pictures in his 68-year-career, which have been exhibited throughout the country.

His works were on display at the Hà Nội Museum four years ago, which showcased 12 typical types of Vietnamese folk paintings, such as Đông Hồ and Kim Hoàng.

“I think this craft will be lost, because there are few enthusiasts nowadays,” Tai said sadly. “It takes a great deal of time to become a skilled artisan, and I’m already too old to teach others.”

He now views making embossed fabric pictures as a way to enjoy his twilight years.

“I still dream that, as long as my health allows, I could hold an exhibition of 70 or 80 of my fabric pictures,” he added. “I also dream that such an exhibition would be people’s final memory of me.” VNS