Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

When the Vietnamese celebrate Tết, they say ăn Tết, literally “eat the Lunar New Year”. During the festivities, which traditionally last a full month in Việt Nam, food is a primary focus.

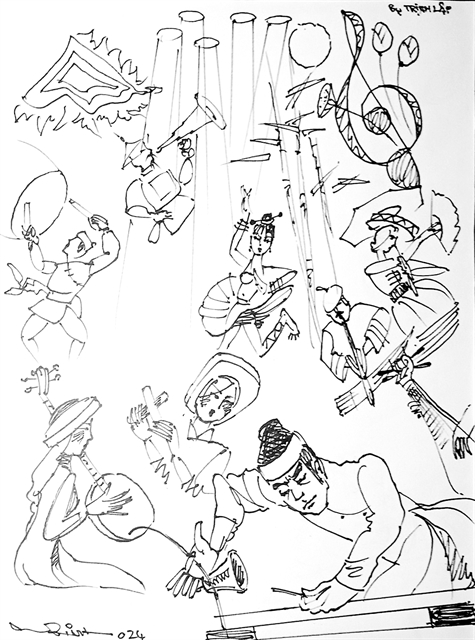

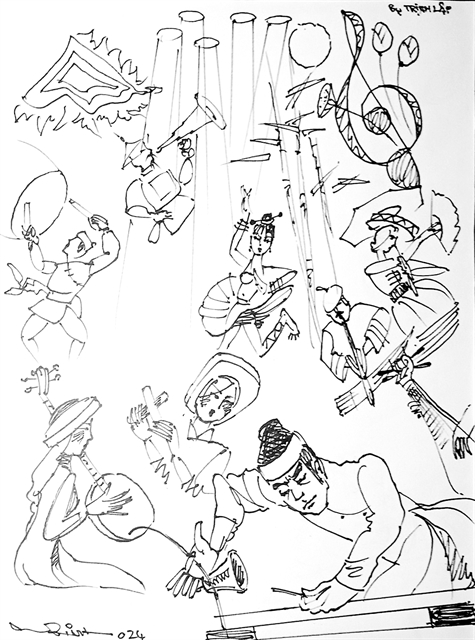

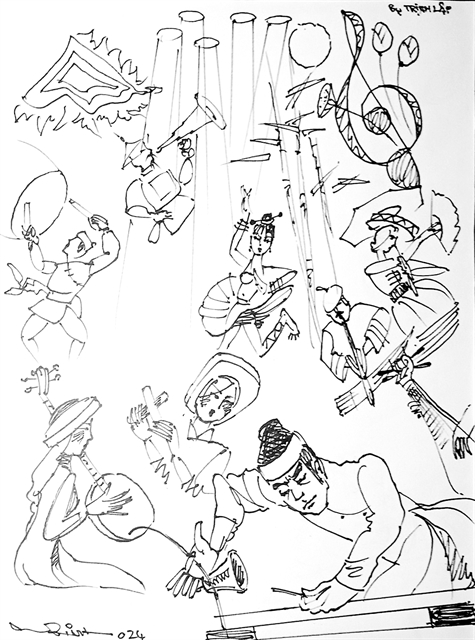

|

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Andrea Nguyễn*

When the Vietnamese celebrate Tết, they say ăn Tết, literally “eat the Lunar New Year”. During the festivities, which traditionally last a full month in Việt Nam, food is a primary focus. But people actually take in the holiday with all their being. Tết is the most important event of the year, symbolizing rebirth, family, and relaxation. It is like Christmas, New Year, Easter, Thanksgiving and Yom Kippur all bundled together.

Many overseas Vietnamese, nostalgic for days gone by, return to Việt Nam to spend Tết with family and to pay respect to elders and ancestors. People are busy in the days before the first day of the Lunar New Year, known as Tết Nguyên Đán. They clean their homes and then decorate them, particularly with flowering branches of yellow hoa mai (ochna) or pink hoa đào (similar to apricot, peach and quince blossoms).

Everyone shops for specialty items wrapped in auspicious red and gold packaging. Superstitions abound as people try to ensure good luck, prosperity and happiness for the future. Among them is the belief that the first person to offer Tết greetings at your home will share his or her good fortune with you in the coming year.

At the centre of the hubbub is the food, most of which is prepared in advance to allow people plenty of time for fun once the holiday begins. While regional differences exist, typical dishes include such rich meats as long-simmered kho made with pork or beef and various giò and chả sausages; pickled and preserved vegetables to cut their richness; and candies and sweetmeats to refresh the palate.

But regardless of the region, bánh chưng are always on the menu. The square sticky rice cakes are wrapped in green leaves (dong leaves in Việt Nam; banana leaves abroad), then boiled for up to twelve hours, depending on their size. Small ones measure four to five inches (10-12cm) wide and larger ones are the size of adobe bricks. The outer layer of rice becomes perfumed and tinted by the green leaf. Inside, the grains remain white and encase a buttery bean filling streaked with pepper and studded with chunks of lean pork and bits of its opaline fat.

Bánh chưng may be eaten warm or at room temperature; they may also be panfried up as crispy pancakes. (When the same ingredients are wrapped as cylindrical cakes, they are called bánh tét.) Because they are inexpensive to prepare and they keep for a long time, Vietnamese families traditionally cooked up dozens of them.

My parents, who are now in their eighties, revel in describing the sequence of events that went into making the cakes when they lived in Việt Nam. Two days before Tết, the ingredients were gathered and readied. The next day, everybody from young to old got involved in wrapping and boiling the cakes, which lasted from early morning to late at night. The boiling was done outdoors in huge pots set over a wood, coal or rice-straw fire.

Since the moon barely shone on New Year’s Eve, the pitch black night was lit by people’s bánh chưng fires. Everyone eagerly anticipated their first tastes of the cakes, especially the children, some of whom slept by the fire. By the time the cakes were done, it was already the first day of the New Year, and the leaf-wrapped bánh chưng were quickly carried into the house, where they were prominently displayed to signal the start of the feast.

My Tết celebrations today in California are not that elaborate. However, I do make bánh chưng from a recipe that my mother taught me, and which I wrote up in my first cookbook, Into the Vietnamese Kitchen. She brought the recipe from Viet Nam when we left in 1975. I use a wooden mold that an American friend made for me.

Many Vietnamese people nowadays buy bánh chưng because they lack time and perhaps know how. I understand, but after all these years I can tell you this: Bánh chưng is a magical thing.

You can count the number of ingredients on one hand. With those ingredients and some leaves, you can create a three-dimensional edible object that looks like a gift box. And that culinary origami is sturdy enough to endure hours of boiling. Finally, when you unwrap your bundle of joy, it is incredibly fragrant and beautiful.

The simple deliciousness and genius of bánh chưng embodies the grace and spirit of the Vietnamese people. It is a food marvel, conjured from humble ingredients. It is incredibly Việt. Most importantly, it makes me very proud. VNS

*Andrea Nguyễn, Vietnamese-American cook and author in California