Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

Overparenting is nothing new around the world, but it is increasingly popular in a modernising Việt Nam. With smaller family sizes and different standards of living, some Vietnamese parents regard their one or two children as 'treasures' that demand extreme care.

|

by Vũ Thu Hà

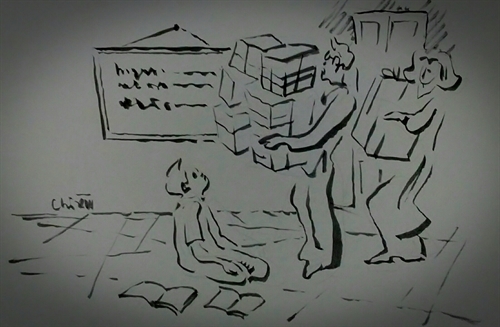

Nguyễn Duyên, a mother living in Phước Đồng Commune, Nha Trang City, started a public debate two weeks ago when she posted a video on her Facebook showing a group of fourth-grade students, including her child, carrying a desk down the stairs at their school.

“As a parent, everyone wishes to see their children—looking nice and tidy in their uniforms—exposed to a “clean” environment at school. Here, however, the reality is the total opposite of the wish”, Duyên wrote on her Facebook.

Her post quickly went viral. Within a few days, it amassed nearly 900 shares and received a long thread of comments from an array of viewpoints.

Parents who agreed with Duyên complained that the job was too tough for children of that age.

“The school should have taken care of this task before class started. Why would they force the children do that? If the children had fallen down and broken their arms or legs, would the school bear the responsibility?” Facebook-user Lien Kiem commented.

Nguyễn Giang, a father of two, even accused the school of "exploiting" the students.

There are also people who think otherwise.

“There is nothing wrong with children doing manual work at school. It is an important component of studying, especially once you take into account the fact that many children don’t do manual work often and therefore become lazy and dependent,” wrote Nguyễn Thị Thu.

“By being overprotective, it is in fact the parents who make it difficult for teachers to educate children,” Nguyễn Hoàng Huân commented.

Overparenting is nothing new around the world, but it is increasingly popular in a modernising Việt Nam. With smaller family sizes and different standards of living, some Vietnamese parents regard their one or two children as ’treasures’ that demand extreme care.

Just last year, a mother in HCM City was seen trying her best to push her motorbike forward against a flooded street in a heavy rain. On the back of the motorbike was her son, who would not have been characterised as “small”.

Yes, risks do exist. There is nothing wrong with parents fearing for their children’s safety.

The question is, however, whether parents should shield their children all the time. Should we not encourage them to overcome their fears and expose them to the realities of the world? Do they not need to face challenges and hardships in order to grow up independent and dauntless? Parents must remember: you will not always be by their sides day and night.

Ancient Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca once said: “A gem cannot be polished without friction, nor a man perfected without trials.”

Duyên’s story reminds me of an experience I had with my own son when we were living in Japan and he was in nursery school.

In Japan, young children regularly do chin-ups or walk several kilometres a day, excersise expected of even two-and-a-half-year-olds like my son at that time. As a typical Vietnamese parent who is often obsessed with my fears, I had a lot of worries that kept my mind on edge. I feared that my little boy would fall down from the horizontal bar hung high above the ground while doing chin-ups; I feared that his small legs could not bear walking such a long way; I feared that he could catch a heat-stroke during summer, etc. When I confessed my worries to his teacher, she asked me to believe in my son and to give him a chance to prove himself.

“Believe me! He can do it.” she told me.

To my surprise and admiration, my son quickly became proficient in chin-ups. In fact, he got very excited each time he walked up to the bar. And now, at the age of three-and-a-half, he is able to walk a long way. For example, he can trek the 2.5km leg around the lake near my house without any complaints or requests for help – a thing many of my friends’ children could not do. Had I not thrown away my fears, my son would have never discovered his limits.

Doctor Nguyễn Lan Hải, an expert in childhood education, said that many Vietnamese people nowadays seem to have a longer childhood due to parents’ overprotection.

“Not only do parents try to overprotect their children when they are small, but as a habit, they also continue to intervene in their children’s lives when the kids grow up—from things like what to eat, where to go, or how to study, to bigger questions like whom to marry or which house to buy,” Hải said.

Back to Duyên’s story, Dr. Vũ Thu Hương, member of the Faculty of Primary Education at the Hà Nội University of Education, told online newspaper zing.vn that by posting that children shouldn’t have to carry a desk downstairs, parents are contributing to a “generation living in incubator” that will find it hard to mature later in life.

“The children were carrying the desk to serve themselves. If they cannot do such a simple job, what else won’t they be able to do in the future?” she asked.

You may or may not agree with Hương’s opinion, because defining what is “simple", “safe”, or “doable” differs from person to person. In child-rearing, it really is your choice to set your own limits and boundaries, because at the end of the day, it is you and your family who reap what you sow.

As for me, I will try to follow what Dr Wendy Mogel, an American parenting expert, said in her best-selling book The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: “Real protection means teaching children to manage risks on their own, not shielding them from every hazard.” — VNS