Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

One of the remarkable aspects of Tết is that it celebrates both personal and national identities. To celebrate Tết is to be Vietnamese.

|

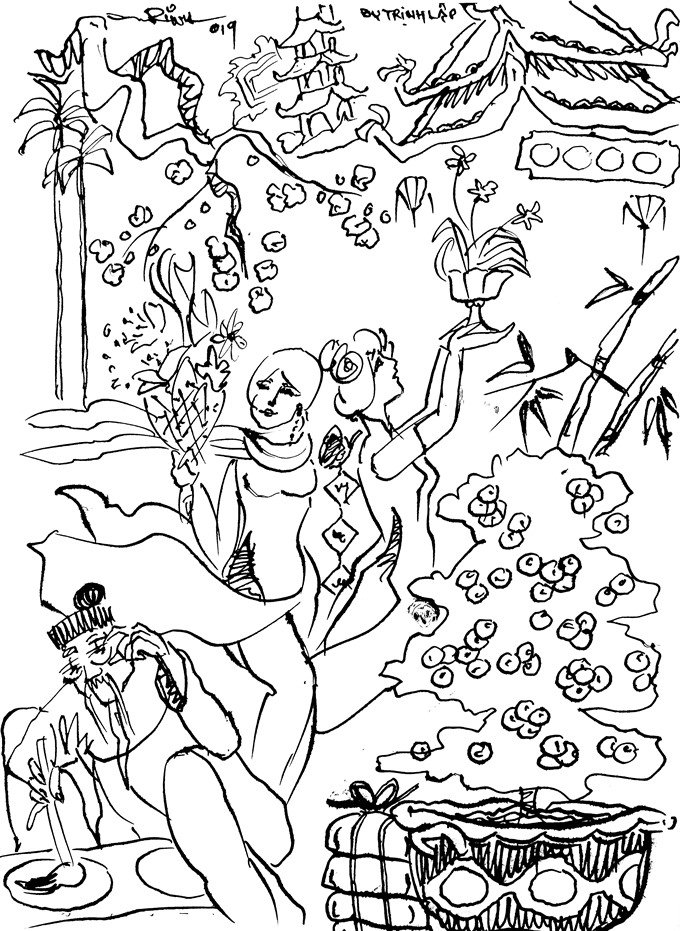

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Mary Pecaut

I first set foot in Việt Nam in 2014. As a US citizen embarrassed by my country’s policies during and following the American-Việt Nam War, I was uncertain about the welcome that awaited me. Because I spoke French and had family members living in Toronto, I prepared to answer that certain-to-be-asked question: Where are you from? By replying, Canada.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that US citizens are very welcome in Việt Nam and that there was no need to hide my identity. Upon arrival, I started my quest to understand my new home country and her people. Usually when I arrive in a newly assigned country, I dive into the local culture through food, art and language. I soon discovered that the best window into Vietnamese culture was by understanding a unique Vietnamese national holiday.

Tết Nguyên Đán, otherwise known as Tết, is the most important and popular holiday in Việt Nam. The word Tết comes from the Vietnamese word tiet - the knotty internode on a bamboo stem which has come to mean a transition between seasons. There are numerous Vietnamese Tết festivals, but none as extravagant as the Lunar New Year also considered as the beginning of spring when we welcome in the new, assess the past year, and commit to the future.

My first impression of Tết was that it was similar to the Chinese New Year, but with a Vietnamese twist. Employers presented red envelopes of money to their staff, calligraphers wrote New Year wishes in Chinese characters and horse statues representing the animal zodiac signs for 2014 were on sale in abundance. While there are similarities with Chinese New Year, Tết is not just a New Year celebration. It is more than saying good-bye to the old and hello to the new. Each year living in Việt Nam, I have gleaned more about the significance of this 3-10 day celebration.

Tết is based on a lunar calendar. Because my husband is Muslim and all of the religious holidays in Islam are based on a lunar calendar, I understand how countries may follow two different calendars simultaneously.

My husband and I ‘ate our first Tết’ in Hà Nội in 2014. The excitement and anticipation in the weeks before Tết were palpable. Vietnamese friends cleaned and decorated their homes. Motorbikes streamed by with orange fruited kumquat trees in clay pots strapped to the back. Branches dotted with pink blossoms decorated family altars.

At the cemetery in my neighbourhood, tombstones were cleaned and the gardens around them weeded.

While I observed this activity, I didn’t realise until years later that preparations were being made to invite the spirit of ancestors to participate in the festivities. I knew about the practice of ancestor veneration and greatly appreciated the prominence of family altars in each home, but I was surprised to discover that Tết is not just for the living. It is a celebration which brings the living and the dead together.

It is a way to transcend our notion of time - merging past, present and future.

My husband and I joined members of Friends of Việt Nam Heritage at a presentation about the Kitchen God. One by one, we knelt by the lake and released small carp, sending sacred messages to the Jade Emperor in heaven. Tết is not only a time to honour ancestors, but also household and heavenly deities.

"Chúc mừng năm mới" replaced "Xin chào" as we greeted people on the streets and in the shops. With so much practice repeating best wishes for the new year, I’m quite certain that "Chúc mừng năm mới" was the first phrase in Vietnamese that I pronounced correctly!

In the days just before Tết, Hà Nội experienced a mass exodus as families returned to their hometowns. Those who could afford to travel from overseas were choosing to come home at this time of year. One friend’s brother was arriving from Germany after many years abroad. Anticipation of his arrival added to the excitement in their household. Tết was clearly a time for families to reunite.

The eve of Tết, a hush fell over our neighbourhood. Just after midnight, we heard drumming, welcoming the New Year, and signifying the completion of special prayers by families inviting their ancestors to join in the Tết festivities of the next ten days.

On day 1, Hà Nội was transformed into a quiet village. My husband and I walked the circumference of Tây Hồ, stopping at each temple and pagoda along the way. Families dressed in new clothes lit incense, bowed before the altar, and burned paper votive offerings including fake money. Women in brightly coloured áo dài - many of them dressed in red - posed for photos against the backdrop of the lake.

As we approached Phủ Tây Hồ, a temple dedicated to Princess Liễu Hạnh, the street leading to the gate was packed with colourful stalls selling snacks like bánh tôm, prawns cooked in a thick batter as well as sweets, cakes, fruit, and incense. Bearded elderly men wrote prayers for visitors to burn to send to the gods and goddesses.

Inside Phủ Tây Hồ, visitors bowed before the three mother goddess statues: Mẫu Thượng Ngàn wearing green to represent the forest, Mẫu Thoải dressed in white, symbolising water; Mẫu Địa in gold, symbolising the earth. We were told by a young temple visitor that those who desired fertility blessings often prayed there.

As we visited the holy sites, I could see the influences of ancestor veneration, mother goddesses, Confucianism and Buddhism converging. Tết invokes a spirituality beyond any one practice. It provides a way to connect to nature, the Divine, family, friends, and complete strangers and to our better selves - the person we want to become in the New Year.

The next day, a few close friends who did not travel back to their hometowns came to call bearing gifts of bánh chưng. Attentive to my husband’s dietary restriction of no pork, they brought a vegetarian version - square packets of delicious glutinous rice with mung beans steamed in dong leaves. Like many busy households they now buy bánh chưng rather than make it at home. Traditionally, children helped prepare bánh chưng and while they waited for it to boil for eight hours, family members would read stories to them.

In life, change is inevitable. Some Tết practices are disappearing. I am told that the doors of homes in Hà Nội were once decorated with red scrolls of câu đối (parallel sentences) on each side of the door. Older generations in Hà Nội describe offering money to singing children who would come to their home, tapping bamboo sticks filled with jingling coins.

There are two essential human needs - to be grounded in our understanding of who we are individually and to belong to a community. Vietnamese have a shared heritage as descendants of the Royal Water Dragon, Lạc Long Quân and the mountain fairy Âu Cơ. One of the remarkable aspects of Tết is that it celebrates both personal and national identities. To celebrate Tết is to be Vietnamese.

During Tết the entire country focuses on reconnecting with its heritage, hometown, village life, ancestors, friends and family. From dragon parades and lion dances, to village banners and home decorations, from sugared dried fruits to peach flowers, the Vietnamese culture shines.

Now that I’ve been assigned to another country, Việt Nam seems far away. Yet as Tết approaches, I feel a deep sense of nostalgia. I never cooked bánh chưng while living in Hà Nội, yet now I find myself looking up recipes. Most ingredients are available here and I rationalise that banana leaves may be substituted for dong leaves. And surely I can make cake molds out of wood. But where will I find a kumquat tree? — VNS