Features

Features

A famous pediatric surgeon in Việt Nam continues to break new ground as he strives to make small but life-changing improvements for patients and their parents. Thu Vân reports.

|

| Professor Nguyễn Thanh Liêm conducted a stem cell transplantation surgery for a child with cerebral palsy. Photo Courtesy of Vinmec International Hospital |

A famous pediatric surgeon in Viet Nam continues to break new ground as he strives to make small but life-changing improvements for patients and their parents. Thu Vân reports.

Fame is not a driving force for Nguyễn Thanh Liêm.

He is already recognised as a leading pediatric surgeon in the country and in the world who has done pioneering research and successfully applied many surgical techniques

Given the kind of patients that he treats, he cannot even hope for complete cures, most of the time.

|

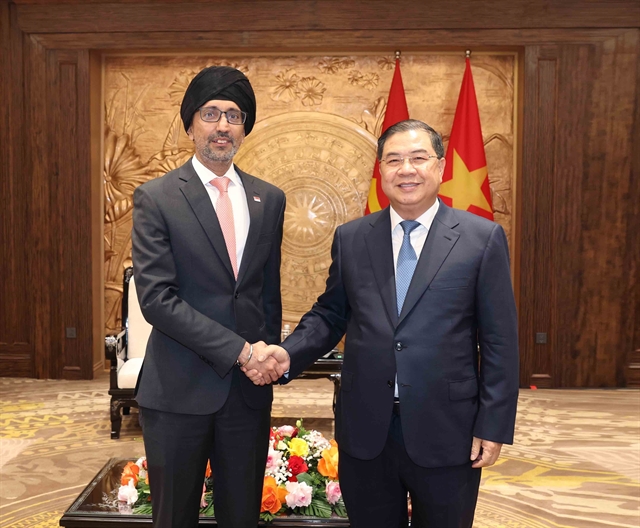

| Professor Nguyễn Thanh Liêm |

But when Liêm thought of using stem cell therapy for a two-year-old cerebral palsy (CP) patient, “many people doubted the idea and thought I was trying to do something shocking to promote for the image of the private hospital that I was working for at that time”.

Liêm smiled as he recalled what happened almost four years ago.

On a winter day in late December, Liêm received a boy in really bad condition.

He was told the two-year-old boy had diarrhea, high fever, convulsive fits and sepsis of an unknown cause when he was 10 months old. The baby was treated at a local hospital and survived, but suffered convulsions, had difficulty breathing and could not sit or crawl. Doctors diagnosed cerebral palsy.

Liêm asked his assistant at the Vinmec International Hospital, Doctor Vũ Duy Chinh, a rehabilitation expert, to join him in examining the cerebral palsy patient.

“Cerebral palsy is caused by damage to the brain’s motor control centre, which consists of several parts of the brain and billions of different cells, and there might be various causes to this,” Chinh said.

“It is connected with a range of symptoms, including muscle weakness and movement problems, like difficulties in walking, balance and motor control, eating, swallowing, speech or coordination of eye movements,” he said.

Chinh told Liêm that until then, the only treatment for cerebral palsy was physiotherapy and rehabilitation, combined with drugs to mitigate certain symptoms. Overall, the treatment was not very effective.

“At that moment, I suddenly thought of stem cell therapy, a method which I had already used to treat patients with liver cirrhosis or biliary atesia,” Liêm said.

“The initial idea and theory is that stem cells can develop into specific types of brain cells, replacing those which are damaged,” he said.

It took him three months to follow up on the idea: to study it further, ask for permission from the hospital’s leaders, prepare necessary equipment, and prepare himself to do it.

“I didn’t say it out loud, but a part of me was nervous – it was the first time such a technique was applied in Việt Nam. And I know many people were skeptical and watching this closely,” Liêm said.

His assistant, Dr Chinh, shared the same thoughts.

“Dr Liêm and I didn’t talk about how we felt about it, we just focused on the preparation for the surgery. But the pressure came, day by day. I totally understand the doubt – we had never done something like that.

“In medical practice, even though we know a therapy has solid scientific ground, everything has its own risks,” Chinh said.

|

| Smiles were back on the faces of Bùi Duy Nghĩa and his mother. |

On March 21, 2014, Bùi Duy Nghĩa, the baby boy, was all set for what could be a life-changing surgery.

Duy was anaesthetized before doctors started to collect stem cells from his own bone marrow. A needle and a syringe were used to aspirate bone marrow from his iliac crests. The process took about an hour.

“It was the first time – so we were extra careful. Later on, it would take half the time,” Liêm said.

The bone marrow was then taken to the hospital’s laboratory for processing and extracting stem cells, a procedure that took about three hours then.

Later, the stem cells were injected into the boy’s spinal cord cavity through a small needle, a procedure that took about another hour.

“We didn’t expect that this therapy would cure the condition. The goal of stem cell transplantation is to reduce symptoms and protect and repair damaged cells before they become completely useless and cause permanent damage. If it works, the life of patients would become more manageable,” Dr Liêm said.

|

| Processing and extracting stem cell at Vinmec Hospital. |

Grateful parents

Three months after the stem cell transplantation, Nghĩa’s family took him to the hospital for the first check.

The improvement in his condition greatly heartened Liêm and Chinh, who had talked to Nghĩa’s parents from time to time on the phone, but hadn’t see the changes first hand.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes – he was so different. I still remembered how he was when we first saw him. He could barely move, eyes were all blank, he couldn’t swallow so the saliva was all over... But three months after, he could sit up and he looked much more nimble,” Chinh said.

“I was so happy, I almost cried.”

In the following months, Nghĩa received stem cell transplants two more times, and also continued physical therapy.

Nghĩa’s mother, Trần Thị Phương, was overwhelmed.

“He started to gain weight because he could eat and swallow. When he listened to me singing he laughed. It was magic for my family. I felt so thankful to the doctors who made this happen,” Phương said.

Phương might not have known that Dr Liêm was himself thankful that the first successful case consolidated his trust in the new therapy.

“I’ve met so many families with so much sorrow, and mothers of cerebral palsy patients who’ve never had a full night’s sleep. Whether or not I would be praised for this did not matter. What mattered was how the new method would cure these kids,” Liêm said.

In Việt Nam, the unofficial number of children suffering from cerebral palsy is around 200,000.

“This could open opportunities for many children to have their lives changed for the better,” he said.

This new treatment is not something that can cure all cerebral palsy patients.

Liêm said there are cases in which stem cell transplantation will not work.

“If patients were born with cerebral palsy, this method will not work. My experience shows that improvements and changes are only seen in patients that contracted cerebral palsy because of drowning, oxygen starvation during birth, or due to meningitis; in general, after-birth developments,” he said.

|

| Nguyễn Phước Thanh Tuyền, who suffered from cerebral palsy, received stem cell transplantation in 2016, now can walk and take care of herself.— Photo Courtesy of Vinmec International Hospital |

Clinical trial

In 2014, Dr Liêm and his colleagues started a clinical trial on 40 celebral palsy patients aged 2 to 15. The study, which was basically using autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for treating cerebral palsy, was completed in August 2015.

But the success of the study does not mean he stopped there.

He thought the method might also work on children with the incurable brain ailment, autism, which is also caused by abnormalities in brain structure or function.

Clinical trials of stem cell therapy on children with autism had been conducted in America, India and China, Liêm said.

"Autism is a burden for families who have to live with it, so even small changes in the behaviour of the kids mean a lot to their parents," Liêm said.

Earlier this year, a study by a group of scientists from Duke University, the US, conducted on 25 children with austism, suggested that most children on the spectrum who received an infusion from their own umbilical cord blood showed improvements in behaviour, communication and socialisation, among other measures, while experiencing no significant downsides from the treatment.

Dr Alok Sharma from India’s NeuroGen Brain and Spine Institute said at a conference held in Hà Nội last November that stem cell therapy had shown promising results after being performed on more than 5,000 children with cerebral palsy and 500 with autism in India.

Under another scientific research project by Dr Liêm and his colleagues that was approved earlier this month by the Ministry of Health, 30 children with autism from three to seven years old will have the chance to have stem cell transplants for free in a time span of 18 months.

Children selected for the trial will be those who have already undergone traditional therapies like behaviour education and medicines but show little progress.

This month, the first four kids will undergo stem cell transplants under the project.

"Although the therapy is still in the early stages and much more research is needed, it is a ray of hope for many who are suffering," Dr Liêm said.

“My motivation is small. I want patients and their families to experience improvements and a better life.” — VNS