Features

Features

Pigeon racing has emerged as a hobby of many HCM City residents for more than a decade.

|

| Ngô Hồng Vân has been raising racing pigeons for over 10 years. Many in HCM City partake in this sport as a hobby. VNS Photo Việt Dũng |

by Nguyễn Việt Dũng

Heads turn upwards around the same time every afternoon around Ngô Hồng Vân's house in Bình Tân District.

They are then treated to an unusual sight: a huge flock of homing pigeons circling the neighbourhood.

This hobby retains its intrigue even after explaining that the racing birds are training for coming competitions. People are even more curious once they learn that pigeon racing is a sport where homing pigeons (a variety of pigeons with an innate ability to remember and return to their nests) are trained to fly home from a considerable distance.

This sport has emerged as a hobby of many HCM City residents for more than a decade. From around 2009, many clubs began forming in the city, and professional pigeon races are held every year.

Vân, who sells spices in District 6's Bình Tây Market, has been raising homing pigeons for over 10 years and is a member of the Hàng Xanh Pigeon Racing Club.

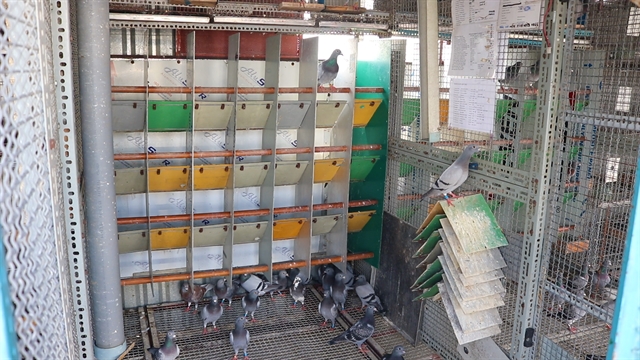

He has converted the top floor of his house into a loft to raise around 100 pigeons.

|

| Pigeon racing lovers convert their houses' top floors into lofts for their birds. – VNS Photo Việt Dũng |

He tells Việt Nam News that pigeon fanciers have to find good racing breeds first to produce some squabs, that are selectively bred for enhanced speed and homing instinct.

"At 6m or 7am every day, I go up to my pigeon loft to care for the young birds, give them medicine, clean out the droppings and look for any problems before going to work. At noon I return to feed them, and in the afternoon, I let them fly around my neighbourhood."

When he opens the loft door, the pigeons rush out and soar high in the sky, flying around his house in a large flock. After doing several laps, they fly back to the loft and make themselves at home.

Vân and other pigeon fanciers typically employ training services, which involve taking their birds far away from their homes and releasing them. The distance can increase to hundreds of kilometres as the birds' flying capabilities improve.

"It costs around VNĐ1 million to raise and train one pigeon until it can race," Vân says.

|

| Perching racing pigeons. The birds are trained to fly back home from a long distance away. – VNS Photo Việt Dũng |

Raising racing pigeons is not easy. They can get injured or eaten by hawks or other birds of prey or drink unclean water outside their lofts.

However, Vân also insists that spending time with his birds is a relaxing experience.

"My workday can be stressful, and being able to spend time with my pigeons, hold them in my hands, and care for them is great for relieving stress," he says.

Nguyễn Tân Phong in District 8 has also been raising pigeons for over 13 years, and he is a member of the Sài Gòn Pigeon Club, the first of its kind in HCM City.

He spends around three hours every day caring for his birds.

He tells Việt Nam News that each pigeon loft is designed differently to suit the conditions of their houses and surrounding areas, helping the birds return to their homes as quickly and conveniently as possible.

This plays an important role in a pigeon race, he says.

"We install cameras to monitor returning birds. They alert us of the exact return time and record the data to keep track of each racer's performance."

According to Tô Chấn, president of the Sài Gòn Pigeon Club, the racing pigeons are neither native nor ornamental breeds. They are all "descendants" of foreign homing pigeon breeds.

"In the past, racing pigeons mainly originated from Thailand and China. Later, more pigeon breeds were imported from Europe. They are vaccinated against diseases from a young age and trained carefully to be able to fly back to the loft after a long distance race," Chấn tells vietnam.net.

|

| A flock of pigeons fly in the sky. Racing pigeons are typically let out to fly around their lofts every day. – VNS Photo Việt Dũng |

Nerve-racking entertainment

Pigeon racing clubs in the city organise up to 10 races a year.

According to fanciers, birds from 6 months old can be trained to find their way home from a long distance away, first from 60km then to as far as 800km.

"A good racing pigeon is capable of flying stably and returning to its loft during training. Depending on the race, I will choose a bird with an advantage in either speed or endurance to participate," Phong says.

"During training, a fancier can train his bird to fly from one to three times for a certain distance to know whether it is physically fit for races or not."

As soon as the bird has overcome the challenges of flight training, its trainer will get it ready for races.

Club members bring their pigeons to a gathering place to register them for the race. After that, the birds get their wings stamped and wear leg bands containing hidden serial numbers that have to be scratched later.

|

| Vân has been partaking in numerous pigeon races over the years. Pigeon racing clubs in HCM City may hold up to 10 races a year. – Photo courtesy of Ngô Hồng Vân |

The birds are then taken to a starting place hundreds of kilometres away from their lofts and then released so they can fly back home. Certain long races of around 1,000km can take the birds a few days to find the way back home, causing anxiety and worry for their owners.

"The races are held in different weather conditions, so it is very difficult for owners to know if their birds will return on time as predicted or not," Chấn says.

Unfortunately, the racing pigeons might never return. It is common for the birds to go missing during races as they might get exhausted or die along the way due to bad weather or natural enemies such as birds of prey, or even human attacks.

"On the way, the racers have to overcome many challenges, so it is a great pride to see the birds flying back," he adds.

"When returning to the loft, the pigeons often show signs of fatigue, even ruffled feathers, or have wounds on their bodies. Seeing the birds return home safely after each race is the happiest moment for the fanciers."

After the pigeons return to their lofts, their owners are quick to scratch their leg band to reveal the bird's individual number and text it to the organisers to confirm that their birds have returned.

"Looking at my pigeons arriving from afar is nerve-wracking. Sometimes after scratching the serial number, I even mistype it by accident," Vân says.

Vân hopes that more people will come to know just how entertaining and exciting this hobby can be, and that increasing numbers of people will take it up in the coming years. VNS