Sunday/Weekend

Sunday/Weekend

By Lê Việt Dũng

High in the mountains of the northern province of Cao Bằng reside the Dao Tiền, a subgroup of the Dao ethnic minority people, who, unlike many communities worldwide that have surrendered to the ease of factory-made clothing, cling fiercely to their heritage, weaving and dyeing their garments by hand.

This dedication to tradition is not just about aesthetics; it's about preserving their cultural identity for future generations. Here, every stitch and motif carries a story.

According to Bàn Thị Liên in Hoài Khao Village, Quang Thành Commune, Nguyên Bình District, the Dao Tiền have long been renowned for their cotton growing. The cotton planting season begins around mid-February, to avoid the frost and early spring rains that could damage the plants.

The harvested cotton is dried in the sun, ginned, and cleaned of twigs and leaves before being stored away. During the off-season, they separate the seeds from the cotton fibres and use a spinning wheel to turn the fibres into yarn.

Before being placed on a handloom for weaving, the yarn is soaked in cold water and boiled with glutinous rice and the root of a wild plant. After some hours of boiling, the yarn is removed and beaten into smooth threads.

Dao Tiền girls learn to sew in their early teens, making them highly skilled by adulthood. A hardworking Dao Tiền woman can complete a set of clothing in about two days.

|

| A Dao Tiền woman embroiders patterns on her scarf. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

The finished garments are dyed with indigo. The Dao Tiền plant indigo plants in March, and harvest them three months later. The harvested plants are placed in large vats and soaked for about three days.

After soaking, the indigo dregs are removed, and a bowl of lime is added to the vats. If indigo foam emerges and disperses, the dye has reached the desired standard. The liquid is then drained, leaving behind the concentrated indigo paste.

|

| A view of the community-based tourism village of Hoài Khao from above. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

They combine the paste with freshly prepared indigo solution, a concoction infused with herbs and fireplace ash. The garments are then immersed in this dye bath, beginning a time-consuming process.

Every 20 minutes, the garments are removed, sun dried, and then returned to the bath. This cycle is repeated multiple times until the desired shade of indigo is achieved. A single piece of fabric may require months of dyeing to attain a deep, enduring hue.

"I learned indigo dyeing when I was 13. Every family in Hoài Khao has indigo-dyed garments that women wear throughout their lives," Liên said.

|

| A Dao Tiền woman (unseen) prepares indigo paste for cloth dyeing. — VNA/VNS Photo Lưu Trọng Đạt |

The Dao Tiền adorn their garments with two distinct techniques: embroidery and beeswax printing. Embroidery, often gracing shirts and scarves, features a rich tapestry of motifs, each carrying profound symbolic meaning.

Among these motifs are wave patterns representing the cyclical nature of life, egg-shaped patterns, dog- and sheep-shaped patterns, swastika, pigsty-shaped patterns, and the revered Bàn Vương insignia.

|

| Bàn Vương insignia embroidered on Dao Tiền women's headscarves. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

According to legend, Bàn Hồ, a five-coloured dragon dog, descended to Earth and gained the favour of King Bình Hoàng. For his heroic act of killing the king's arch-enemy Cao Vương, Bàn Hồ was given a princess in marriage.

Bàn Hồ then transformed into a human, married the princess, and was granted the title of king by his father-in-law, becoming known as Bàn Vương. The Dao people in general revere Bàn Vương as their ancestor.

The Dao Tiền embroider Bàn Vương insignia as a tribute to their ancestor, seeking his divine protection and blessings for their descendants' wellbeing. They also believe that adorning a deceased person with a garment bearing this motif during their final rites ensures his acceptance into the heavenly realm.

|

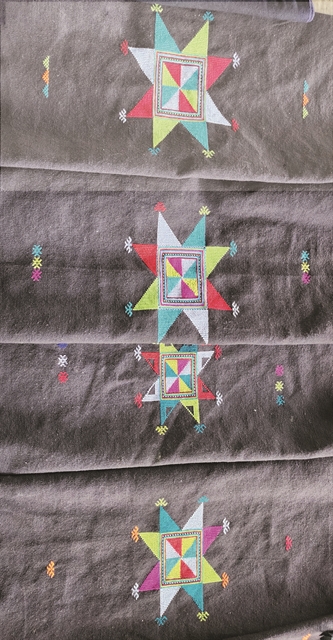

| Eight-pointed stars embroidered on Dao Tiền groom's garments. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

Beeswax printing patterns on ethnic Dao Tiền skirts feature three primary motifs: concentric circles intersected by cross-hatching, resembling a wheel; parallel straight lines; and parallel zigzag lines.

|

| The three typical patterns on a Dao Tiền skirt. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

Lý Hữu Tăng, chief of Hoài Khao Village, said that the Dao Tiền go to the cliffs where wild bees make their nests to collect beeswax, a precious 'ink' used to print patterns on cloth.

When the forest flowers bloom in spring, the bees return to the cliffs to build their nests. By late autumn, as the weather turns cold, the bees move elsewhere to avoid the chill, leaving behind hives filled with wax.

They wait until the bees are gone before calling a shaman to perform a farewell ritual and sending young men to climb the cliffs to collect beeswax. The offering tray consists of three chickens, six glutinous rice balls, wine, incense, and ceremonial papers.

"The collected beeswax is cleaned, melted, and distributed equally to every family in the village. The conservation of the wild bees is enshrined in the village's covenant," Tăng said.

Villager Nguyễn Thị Duyến said that printing tools are elementary: bamboo tubes of varying diameters are used to create circular designs whereas thin, sharpened sticks bent into triangles to print straight lines and angles.

They place beeswax on hot coals to melt and dip the tools into the melted wax to print patterns on white fabric. When the beeswax is dried, the fabric is dyed multiple times with indigo (typically 15 to 20 times).

After absorbing enough dye, it is dipped into boiling water. The heat causes the beeswax to melt away, revealing white patterns against the indigo background. They use these patterned fabrics to make skirts.

"It takes about a month to complete a skirt. The Dao Tiền can tell just by looking at someone's skirt whether she is skilful and diligent," Duyến said.

|

| A group of Dao Tiền women instruct tourist Công Hải Anh (left) and her friend on beeswax pattern printing. — VNS Photo Lê Việt Dũng |

The Dao Tiền's clothing also features a set of silver buttons for decoration. Each button is a round silver piece with a diameter of about 6cm. The pattern on the piece is a concentric circle with a 12-pointed star in the centre, resembling the sun motif found on ancient Đông Sơn bronze drums.

To promote tourism and preserve Dao Tiền's clothing-making techniques, Nguyên Bình District authorities approved a scheme to build a community-based tourism village in Hoài Khao in 2018.

The scheme includes infrastructure development, road construction, electricity supply, and the building of a facility to display farming tools, costumes, and household items of the Dao Tiền. Villagers are trained in basic tourism knowledge and hospitality skills.

|

| Villager Bàn Thị Liên (right) helps a visitor try on Dao Tiền's garments. — VNA/VNS PhotoVNA/VNS Photo |

It officially came into operation in 2020, attracting many tourists to enjoy the pristine beauty of the mountains, savour local specialities, and experience printing patterns with beeswax.

"I came here to enjoy hands-on experience in beeswax pattern printing and immerse myself in the rustic scenery," said Công Hải Anh, a visitor from Hà Nội.

As Hoài Khao embraces tourism, a sense of renewal fills the village. Homes are being revamped, and the chatter of women working together paints a vibrant picture of an ethnic community determined to keep its traditions alive. VNS