Society

Society

|

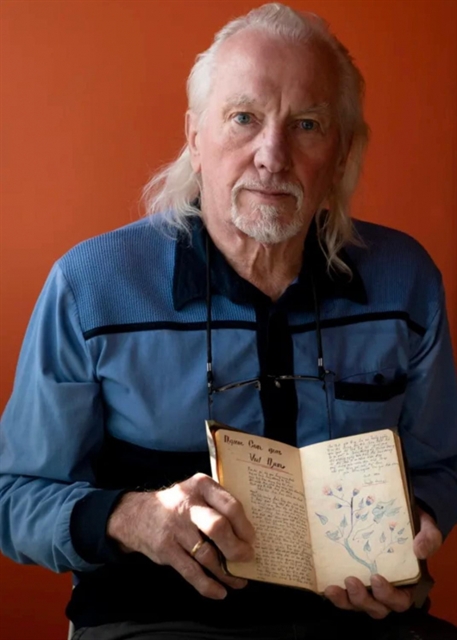

| US veteran Peter Mathews, pictured with the notebook. — Photo courtesy of Peter Mathews |

HÀ NỘI — After one of the fiercest battles during the war time in Việt Nam, US soldier Peter Mathews came across a notebook left behind by a Vietnamese soldier, which he brought back to the States.

Now, 56 years later, Peter has found the notebook's original owner – Cao Văn Tuất, a martyr born in Kỳ Anh, Hà Tĩnh Province, the Dân Trí e-newspaper reported.

Miles across the world

"We were involved in a 30-day battle over a town named 'Doc Toe' (Đắk Tô) in November of 1967," Mathews said to the North Jersey newspaper on finding the notebook.

"After the battle died down, we always go to sweep the area for information. I found a backpack between several dead Vietnamese soldiers. We looked through it and I found a booklet," Mathews added.

"It did not look like a booklet that had military information, so I kept it," explained the veteran. "If it looked like it was militarily [important], I would have turned it in. I kept it on me for another month because I was due to go home in December."

When Mathews got home, he became a US citizen. The diary was sometimes taken out of storage to show family members, but other than that it spent most of its time in Mathews' attic.

“My son has always complained how I never talk about it. This has opened me up a bit," said Mathews.

The notebook may have stayed there forever had it not been for a strange coincidence that rekindled Mathews' interest in the book.

When Mathews was working at a job in Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, he spotted a nón lá, a traditional Vietnamese hat, in his customer's office.

His client had adopted two children from Việt Nam and had visited the country. Mathews brought him the diary and his client offered to have one of his friends translate some of its pages.

Mathews began posting pages from the diary on social media, hoping to get more information. A professor at Harvard reached out wanting to research the diary with his students, and a collector offered Mathews US$1,200 for the booklet.

Mathews got advice from Andrew Pham, who translated the bestseller I Dream of Peace, the wartime diary of doctor Đặng Thuỳ Trâm, and Frances Fitzgerald, a journalist who covered the war and wrote the introduction to Pham's book, should he want to explore getting the diary published.

The last vestige

Mathews, born in the Netherlands, migrated to the United States in 1963 and was drafted into the US army three years later to fight in Việt Nam while waiting for a green card.

The year 1967 marked a high point in the resistance war against America, and the month-long battle of Đắk Tô, in the Central Highlands where Mathews fought, was one of the most brutal.

According to Mathews, the backpacks of Vietnamese soldiers were usually dropped in an area nearby. It was at the bottom of Hill 724 where he found Tuất's diary among the debris of battle.

"I cannot attest to the point that the person was dead because it was not attached to a person," said Mathews, "He could have been alive, he could have been one of the persons laying there."

Tuất, born in 1942, had one older and two younger sisters in a family of six. He joined the army in 1963 and fought many battles in the Central region.

Tuất was confirmed dead on December 10, 1967, around the same time that Mathews found the notebook, but his family did not receive the news until 1972.

Tuất is currently interred in a cemetery in Hoài Nhơn, Bình Định Province, but his remains are not fully regrouped, and Tuất did not even have a remembrance portrait.

The diary Mathews held onto is perhaps the only remaining vestige and memory of Cao Văn Tuất.

"My uncle's passing has left a great hole in our family's life," said Hà Huy Mỳ, Tuất's nephew, "For almost sixty years after he was pronounced dead, my mother and my aunt (Tuất's sisters) kept waiting for news of his remains."

"After we learned that an American veteran currently kept my uncle's notebook, we were so happy that we could not sleep," said Mỳ.

Making art in times of war

The notebook is filled with beautifully intricate illustrations of flowers and landscapes. Tuất also wrote poetry, songs and journal entries in the book.

"I was intrigued by the detail and the artistry," said Mathews, "Whoever wrote it must be an educated person."

|

| One of the pages of Tuất's diary. — Photo courtesy of Peter Mathews |

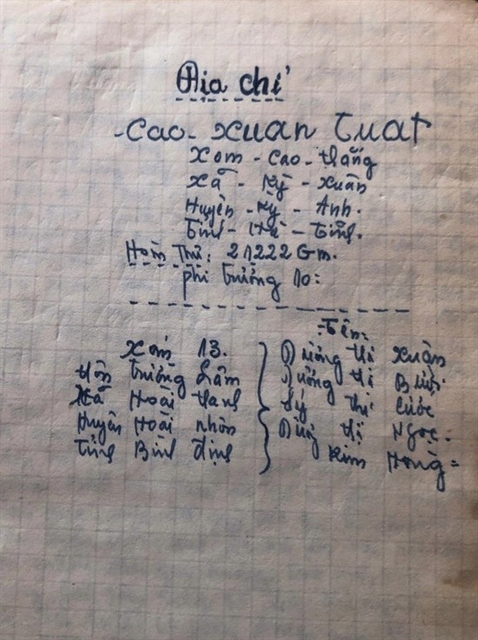

One of the pages of the notebook had a name, Cao Xuan Tuat, which led Mathews to believe that this was the owner's real name.

Three days after Mathews' interview with the North Jersey, Trần Nhật Tân, Director of the Hà Tĩnh Vietnamese Fatherland Front, contacted the US veteran through email.

His daughter transferred the notebook's contents to the Vietnamese officials to verify.

The breakthrough of the investigation came when Mathews sent the page containing details of Tuất's family.

|

| The page of the diary detailing Tuất's family information. — Photo courtesy of Peter Mathews. |

The page detailed the family's address as in Cao Thắng Village in Kỳ Xuân Ward, Kỳ Anh District, Hà Tĩnh. Tuất even wrote his parents and his older sister's name in the book.

The Hà Tĩnh officials quickly went to work and searched hundreds of files on veterans and martyrs with the first name Cao born in the province.

Thirty-six martyrs born in Kỳ Anh had the first name Cao, but only one was named Tuất. However, the middle name was Văn, rather than "Xuan", as written in the notebook. Other than that, the rest of Cao Văn Tuất's details matched what was described in the notebook.

According to Cao Thị Nồng, Tuất's younger sister, the handwriting in the notebook does match his brother's writing. She also said that her brother might have written his middle name as "Xuân" rather than "Văn" as Tuất was very romantic and artistic.

Nguyễn Tiến Huế, a friend of Tuất who also fought in the war, said that Tuất loved art and sometimes showed him his poems and songs. After seeing the pages, Huế also confirmed the handwriting as Tuất's.

Mathews had a website, myyearinvietnam.com, on which he posted pictures and pages from the diary, as well as his own memories of the war.

He plans to travel to Việt Nam soon to meet with Tuất's family and return the notebook.

“I had put a lot of Việt Nam behind me," Mathews said to the North Jersey. "Now, it's bringing up difficult memories and feelings. But maybe it’s good because now I am talking about it.

“There’s a certain sadness that I have — there’s no hatred," he said. "This is a person like anyone else.” — VNS